In April 2014, more than two dozen people were evicted from their informal settlement at the Albany Bulb along the East Bay shoreline. After a complex battle encompassing land-use issues, homeless advocacy, creative reuse and access to public space — and what, exactly, that access should look like — the residents were offered roughly $3,000 each to pack up and leave.

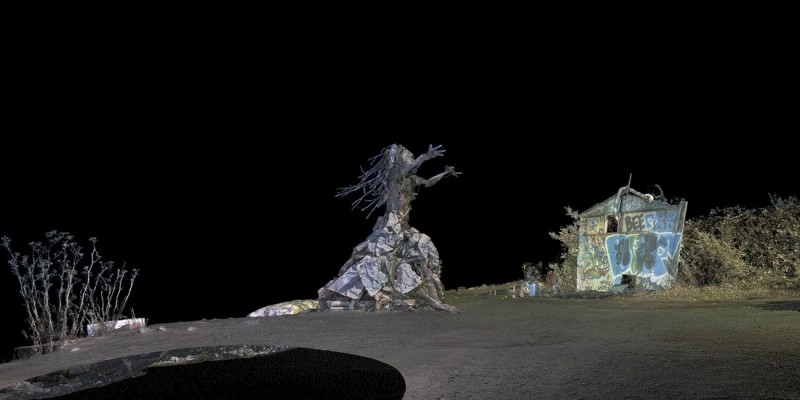

A former landfill owned by the city of Albany, the Bulb has been a hotly contested space for decades. It’s been utilized as a DIY venue for public sculpture and graffiti art, an ersatz dog park, a point of environmental interest and a home to otherwise unhoused residents reclaiming unused materials to build habitable spaces, at least one of which towered at three stories high. And although the last residents of the Bulb have left the space, many have collaborated with several Bay Area artists and SOMArts for an upcoming exhibit, Refuge and Refuse: Homesteading, Art and Culture, which opens Feb. 12 and runs through Mar. 14.

“For me, it was really that combination of the communities of people who lived out there dynamically with the arts, and the place, and the million-dollar views,” says Oakland resident and San Jose State University professor of art Robin Lasser, one of the show’s curators. “I’m exaggerating here, but for me it felt like one of the last places on earth where you had this kind of freedom. For me, [it reflects] the sixties when you had movements of people doing experimental living; life was embraced and politicized and fought for.”

That freedom extended to the art created at the Blub. “One of the incredible things about the bulb and the contested space is that you just do what you do,” Lasser says. “The landfill art that is out there and the graffiti that is out there aren’t sanctioned. Artists didn’t have curators saying what was valuable and what was not.”

Lasser and co-curators Danielle Siembieda and Barbara Boissevain have created an exhibit showcasing the complexities of the political, social and environmental issues around housing, the economy, and the environment. Their work, along with that of many of the evicted tenants, exposes the multiple realities that have coexisted on the land; the collaborative projects give a face to those forced out of a place they once called home.

These “landfillians” include such infamous characters as Boxer Bob, the former professional fighter who constructed a three-story mansion out of reclaimed shipping pallets and other building materials. Another former resident, Mad Marc, lived at the Bulb for nearly 20 years; according to Lasser, Mad Marc retrieved discarded materials by bike and built what the locals call the Fairy Castle, a heart-shaped structure made from discarded grocery carts. The structure, he says, was not meant for human occupancy but was instead built as a gift to San Francisco.

Although the dwellings at the Bulb were demolished after eviction, the show features images of what was once a vibrant, eclectic community. Tamara Robinson and Danielle Evans are among the many former residents with projects on display at the event.

“We wanted to work on an exhibition that could really house all of the stakeholders who have an investment in this place that is truly a phenomena of magic. Not to romanticize things, but I think a lot of people, including those that lived there, felt that way about it,” says Lasser. “But it is a contested space. I think the politics in our country right now — with the division of those who have and those who don’t — gets greater and greater. There are so many people who find themselves out on the streets. Evictions of all sorts are happening to people for all kinds of reasons.”

With housing costs continuing to skyrocket around the Bay Area, the $3,000 from what homeless advocates call a “buyout” from the city surely didn’t go far. Although some former inhabitants moved on to transitional and permanent housing since their eviction, some continue living off the grid in other locations. Many others are back on the streets.

Still, the art aims to capture the spirit of what it means to live, work and create outside of the bounds of societal norms. Audio stories, video, photography, painting, sculpture and additional pieces created and developed through nontraditional artist mediums such as urban planning, landscape architecture and contemporary archeological mapping systems bring to life the multi-layered views of what the Bulb has meant, and continues to mean, to the community.

The exhibit’s free opening reception includes three film screenings, informal discussions with former residents and participating artists, and tours of the LavaMae bus, a project of the Tides Center that provides mobile showers for the homeless in repurposed MUNI buses. A workshop on building mobile shelters with Greg Kloehn takes place Feb. 21, and an “Augmented Reality Tour of Albany Bulb” is scheduled for Feb. 28.

For some, the idea that celebrating art instead of actively working to solve issues around accessible housing may seem insensitive, or at the very least portray a neutrality around the Bulb’s social issues, but Lasser disagrees.

“Rather than thinking of neutrality, I like to think of it as inclusive. If you’re going through that space, you get to make up your own mind about things and be motivated to activate,” she says. “Because of the films and the imagery, I think the indomitable spirit of the people from there will be clear.”