It’s fitting that Marion Gray: Within the Light opened on Valentine’s Day. Gray’s photographs are love letters to a community of performers and artists whose works have come and gone, as ephemeral as those small paper notes. At the Oakland Museum of California, at the far end of the Gallery of California Art, two rooms hold 23 photographs by the Bay Area artist and photographer known for capturing decades of performances, dance and installations on film. Gray’s photographs (many exhibited for the first time), combined with snippets of background information, provide exciting glimpses into both legendary and relatively obscure moments in the local history of these transitory artistic forms.

Curator Christina Linden notes, “The creative communities portrayed in this exhibition have fueled Gray’s work, and her work has, in turn, contributed to the vitality of these artistic worlds.” This exchange is tangible within the exhibition: Gray captures both small details and the larger social conditions of the time, positioning her camera to pull in the audiences, performers and atmosphere of each moment.

Spanning four decades, the exhibition begins with a floor-to-ceiling wall vinyl of Ice Car Cage (1997). Three dancers commissioned by the San Francisco Lesbian and Gay Dance Festival launch themselves from and across a driverless fastback as it moves through an empty lot near the Brady Street Dance Center. A giant speaker hangs off the left side-view mirror. Gray’s flash throws the figures into reverse silhouettes of curved, bent and springing figures in the 12 sequential photographs. Their dance appears exhilarating and frenetic, a clandestine “you had to be there” moment to which Gray provides privileged access.

Other images in the show present just one or two select moments from a performance or installation. The earliest piece is a close-up from Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison’s Sacramento Meditations (1977). One of the artists, dressed in a denim coat with fabulous ceramic eye buttons on both lapels, holds a poster with the text “WHAT IF ALL THAT IRRIGATED FARMING ISN’T NECESSARY?” The photo is tightly cropped, limiting visual information to the bare minimum, and yet it’s clear the figure is in conversation, engaging the public in questions about farming and industrialized agriculture.

Gray’s most recent photograph on view is an overhead shot of Ann Hamilton at the base of the tower she designed at Oliver Ranch, enacting Songs of Ascension (2009), a collaboration with Meredith Monk. She walks through calf-high water as she moves from one set of spiral stairs to another (they loop, double-helix style, up and down the structure). It’s a magical, blue-lit moment.

Other photographs showcase Gray’s ability to capture the dramatic and dangerous. A harrowing piece from 1978 is documented in two parts. Darryl Sapien, “Crime in the Streets: A Performance about Survival in the City” shows performers clinging to two cables above what is now Jack Kerouac Alley; next to it, Gray presents the reverse shot of the huge crowd gathered, their faces serious, below. The precarious trapeze act is echoed in Harold Paris, “The Uncertainty of Looking out a Window (Male)” (1978), documenting a delicate installation jutting from a Stephen Wirtz Gallery window.

A 1985 Survival Research Laboratories performance is full of smoke and fluttering paper — it featured loaded weapons to “terrorize a fake city installed in an empty parking lot.” Sponsored by New Langton Arts, the performance called attention to the violence inflicted during times of war, audaciously harnessed by artists in an intimate precursor to “shock and awe.” A quieter radical moment is an image from the 1984 opening of Moscone Center, in which four well-dressed business people circle Robert Arneson’s Portrait of George (Moscone), the controversial San Francisco Arts Commission-funded ceramic bust of the slain mayor. In Gray’s photograph, the sculpture’s pedestal is draped in black fabric to conceal the words and images covering it (including “Harvey Milk, too” and bloody bullet holes). The result is both bobble-head-like and somber. One woman crouches to sneak a peek at the censored portion. Shortly after this photo, the sculpture would be removed from Moscone Center, rejected by the Arts Commission and returned to Arneson before eventually finding its way into SFMOMA’s permanent collection in 2012.

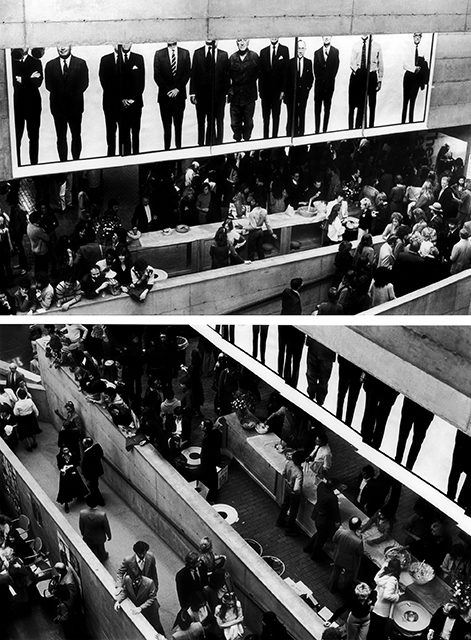

Gray’s camera transports us through time and space. She positions the viewer in the front row for Karen Finley’s 1989 performance A Suggestion of Madness. She cranes our necks at Eiko & Koma as they perform on an outdoor ledge like living sculptures between two towering columns. She captures the excitement of the Artists’ Soapbox Derby — an event, incidentally, that should definitely be reinstated.

Downstairs from Within the Light, the OMCA and SFMOMA joint exhibit Fertile Ground presents work from four distinct circles of Bay Area art history, from Diego Rivera’s crowd to the Mission School. Nowhere within this sprawling show would one have an inkling of the activity documented by Marion Gray. Her work testifies to the raw, immediate, underground and radical practices happening in empty lots, on city corners, bygone spaces and burned-out pits. View them as a supplemental history lesson, a public service, or a remarkable body of work — but definitely view them.

‘Marion Gray: Within the Light’ is on view through June 21, 2015, at the Oakland Museum of California. For more information, visit museumca.org.