At an offsite event to mark the opening of the new Gagosian exhibit Man Ray: The Mysteries of Château du Dé, the band SQÜRL played a live score to four of the surrealist’s 1920s films. It was an exclusive event, invite-only, and intended or not, it established SQÜRL’s soundtrack as the “correct” one for Man Ray’s silent, anarchic works.

SQÜRL (pronounced like the sharp-toothed, bushy-tailed, suburban rodent) consists of just two musicians: Jim Jarmusch, the film director, and producer/composer Carter Logan. To distinguish one from the other visually, you need simply compare the way each man styles his hair. Jarmusch’s untamed, silvery crew cut stood straight up towards the angels painted on the ceiling of the former church hosting the event, each strand electrified by blue spotlights. Whereas Logan’s beard—a small continental shelf—veered downward to the Earth’s turbulent core.

In his brief introduction, Jarmusch murmured into the microphone that he had watched and loved Man Ray’s films as a teenager. Without too much analysis, most of his fans can appreciate the influence of 20th century Dada on Jarmusch’s unique sensibility. You can hear it in the flattened delivery of actors reciting his dialogue. You can see it in the genre-defying non-sequiturs of his most recent film, The Dead Don’t Die.

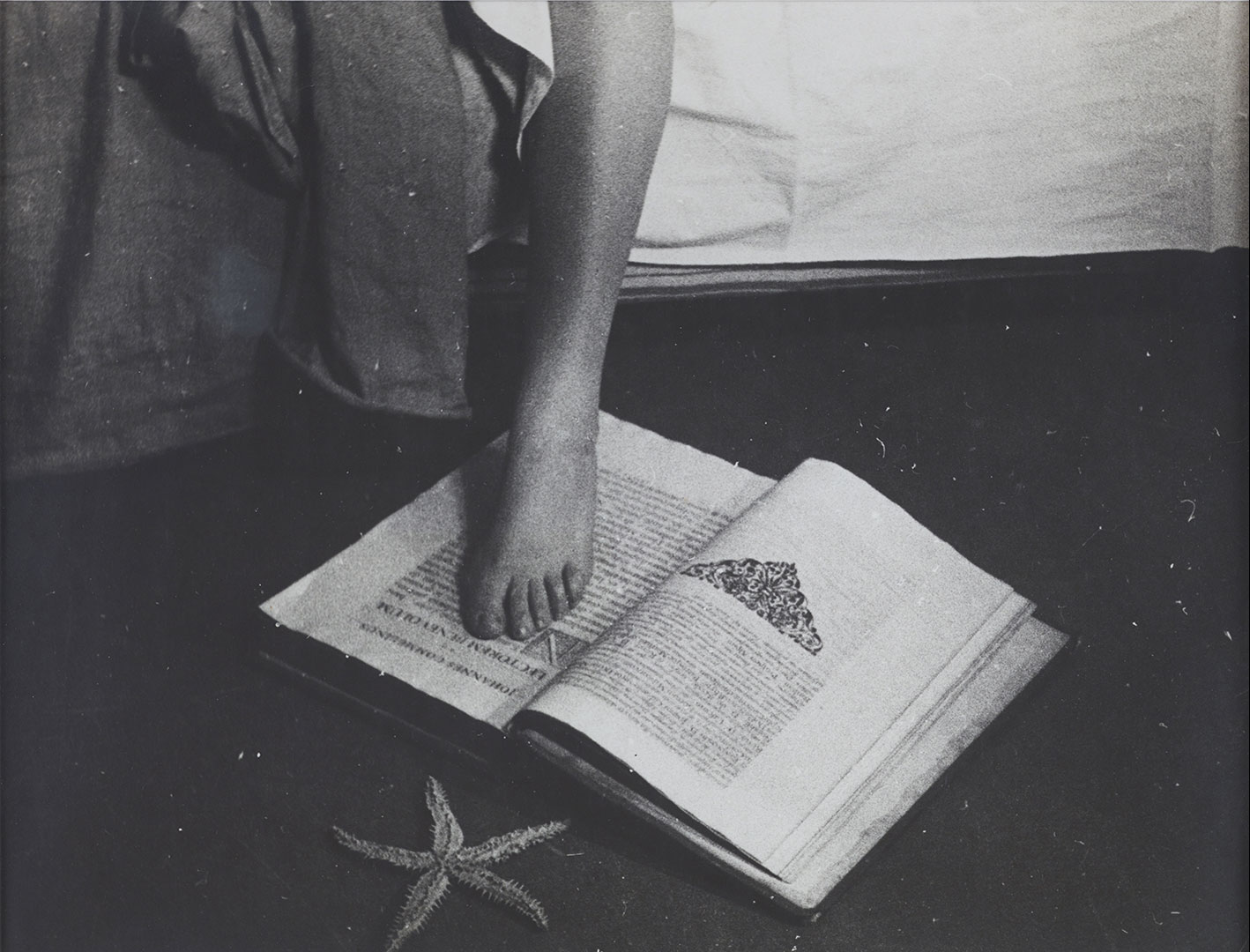

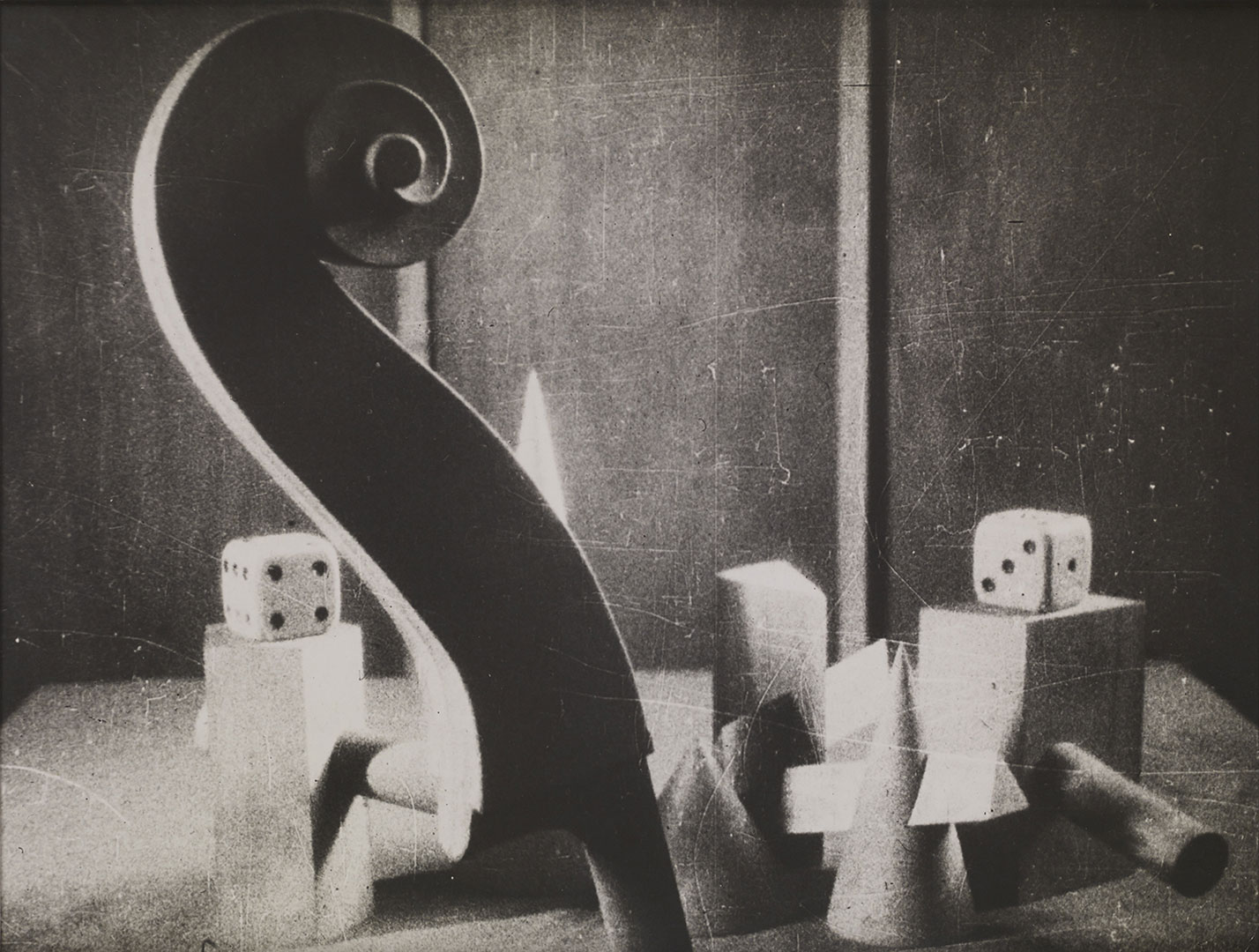

Three of the four Man Ray films that SQÜRL’s music accompanied are now playing in the Gagosian gallery: Emak Bakia (1926), L’étoile de mer (1928) and Les Mystères du Château du Dé (1929). Timothy Baum, the curator who worked closely with the Man Ray estate, notes that Emak Bakia was funded by an expat American stockbroker by the name of Wheeler. He invited Man Ray to his villa near Biarritz to make the film. L’étoile de mer is a “cinépoeme” based on the imagery and ideas in a poem by the French writer Robert Desnos, a fellow surrealist. And Les Mystères du Château du Dé foregrounds a villa owned by Vicomte Charles de Noailles, designed by the architect Robert Mallet-Stevens. Man Ray includes plenty of quick cut edits and strange visual allusions but it’s ultimately a snapshot of an aristocratic afternoon at someone’s perfectly lovely, remote and private castle.

As you view these images in the gallery, there are three sets of wireless headphones resting on benches, offering up soundtracks to viewers of the three projection screens. The curators have selected jazz-inflected music from the same era that the films were made, but it sounds frivolous and bubbly after experiencing SQÜRL’s blend of mysticism and doom.

When Jarmusch and Logan left the stage that night, I thought SQÜRL had imposed a very narrow, but not definitive, meaning upon Man Ray’s films. Logan’s percussive work pairs up ethereally with Jarmusch’s synth loops and echoing guitar chords. It’s an elemental meeting between hell and heaven (their hair should have clued me to this). The compositions filled the World Cultural Center (formerly Our Lady of Guadalupe Church) like a rising tide of holy water that was meant to bless the damned. When a group of men and women swam in a pool on screen behind the band, Man Ray’s film might have been a document of the last post-apocalyptic people left alive.

This is not the sensation provoked by the jaunty dance numbers playing in the gallery headphones. Instead, those same swimmers look like they’re having a blast. Dressed in striped bathing costumes, they shimmy their giddy hips and wave at us before diving into the water. You want to join them because they’re so alive. In SQÜRL’s interpretation, they’re merely ghosts, unearthed from their tombs by the haunting music, shadows dancing for a few fleeting moments.

SQÜRL’s music fulfilled another function I found lacking in the gallery presentation: it focused my attention on the black and white imagery. Without it, my mind drifted away from the blurry faces and repetitive, whirling objects. At that opening event, a blast of SQÜRL’s reverb sent me up into an extraterrestrial dimension, narrative coherence be damned.

To approximate the SQÜRL soundscape for yourself, I suggest you bring your own earbuds and a preloaded smartphone to Gagosian. Man Ray’s films, made shortly after World War I, anticipated the century of warfare and strife that lay ahead; moodier music enhances the messianic implications of the imagery. Play the soundtrack to Only Lovers Left Alive, a Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds album or anything by Angelo Badalamenti.

Sculptures that make cameo appearances in Man Ray’s films appear throughout the Gagosian installation. There are color photographs of the titular Château du Dé; an astrolabe that never stopped spinning on camera; and a giant eye, Le témoin (The Witness), that watches your every move.

But the one object that best embodies the spirit of the exhibit is a petrified starfish resting under glass next to a copy of the Desnos poem. In describing the woman he once loved, the poet is archiving her memory. He transforms her flesh into glass, and then to fire. Tormented by her memory, he shifts the verb tenses from the present to the past, and back to the present again. This emotional fluidity is also present in Man Ray’s cinépoemes, but in the filmmaker’s case they’re made of darkness and light.

‘Man Ray: The Mysteries of Château du Dé’ is on view at Gagosian through Feb. 29. Details here.