There is something antediluvian about world’s fairs. They still exist — one will open in Milan this May — but the concept sometimes feels from another time. The last world’s fair in the United States was held over 30 years ago in New Orleans, and was considered a failure; the more successful fair in Knoxville two years earlier reported a princely profit of $57. Though international events like the Olympics and the Venice Biennale share some similarities with world’s fairs, they still seem more appropriate to the times of Baudelaire and Zola, or at least Asimov and Disney.

On the 100th anniversary of the opening of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition (PPIE) in San Francisco, I visited City Rising: San Francisco and the 1915 World’s Fair at the California Historical Society to search for an answer to why world’s fairs feel so antiquated today. City Rising explores the exposition from its emergence out the rubble of the 1906 earthquake to its demolition in 1916, making use of ephemera, posters, photographs, and even a large-scale reproduction of the fair grounds.

I brought with myself to the exhibition assumptions of national image-building and a narrative about the heroism of industrialism and imperialism. These assumptions were certainly substantiated, but City Rising helps make sense of the tenuousness of this narrative and how it relates to the contemporary condition.

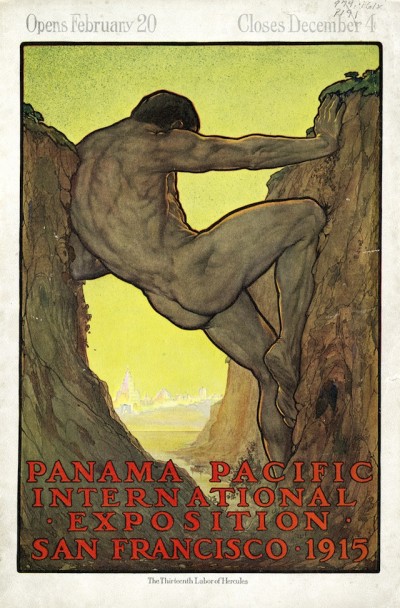

Ostensibly a celebration of the completion of the Panama Canal — an imperial project that overcame malaria, yellow fever, and geography — the exposition more broadly honored the greatness of the United States. A fair poster by Perham Wilhelm Nahl, titled The Thirteenth Labor of Hercules (1915), almost comically suggests that building the exposition was on par with Hercules slaying the Hydra or capturing Cerberus. In the poster, a naked man, washed with muscles, props himself against an enormous canyon wall, moving earth to reveal the “jewel city,” as the the PPIE was known.

A triptych of photographic panoramas documents how the site of the fair looked before, during, and after construction (1912-1915). Viewers see the barren flatlands of Harbor View — now the Marina District — transformed into a beaux-arts metropolis. Part of the land the exposition sat on was once an Ohlone trading village, but by February 1915 it resembled more of a Potemkin village. Though The Thirteenth Labor, the grandiose architecture, and the Hellenic statuary gesture towards confidence and power, there is an air of something desperate in the documentation of the fair. The bluster and pomp hints at the need for a young nation to prove its worth to others, as if it is unsure itself.

City Rising also documents the fair’s deep commitment to commercialism. Though it’s difficult to fully place this in the cultural context of 1915, some romanticism of the fair is lost upon seeing the Gillette Safety Razor booth, the Standard Oil award ribbons, and the Levi Strauss factory in the Palace of Manufacturers. The exposition begins to look like a vessel for advertising, as one is liable to see contemporary events like the Super Bowl: broadcast as a means to sell Skittles and beer. If anything, this is a reminder of the similarities between us and those who lived 100 years ago, even if the assault from marketers is more pervasive now.

Participation in the fair was not limited to corporations. I was pleased to see photographs of a National Child Labor Committee booth, which showed the fair as a place for political exchange. It being 1915, there was also a booth dedicated to the Race Betterment Foundation, which advocated for eugenics and racial segregation. These booths, along with the display of individuals like Elizabeth the Living Doll, a doll-sized person, suggest that the fair was a truly democratic place, with a free exchange of ideas and curiosities. But I am reminded of another place that serves as free exchange of ideas and curiosities, a place fueled by advertising and occupied by eugenicists, labor advocates, and human beings made out to be freaks: the internet.

What the PPIE offered, in terms of marketing, nationalism, politics, and curiosity, can be acquired much more easily and disseminated much more widely now than a century ago. The fall of world’s fairs began well before the rise of the internet, but it did coincide with the development of mass media, including radio and television. A Super Bowl ad can reach many more individuals in 30 seconds than a year-long booth at even the most well-attended fair. An internet ad or labor advocacy blog may find a smaller audience, but they can do so more efficiently, and with more precision, than a world’s fair exhibit.

Beyond changes in marketing, there’s something else that marks the PPIE as anachronistic. This is best explained by curatorial text stating that the fair “evoked the ascendance of American culture and the certitude that science would transform both commerce and society.” For all the cynical motivations behind the fair, City Rising indicates that there was a level of sincerity and enthusiasm for the future, particularly for the promising potential in science and industrialism. The fair notably honored major developments in telecommunication, automobiles, audio recording, and electric lighting.

It is difficult to imagine such a spirit infecting a world’s fair in modern-day America. Though science and technology are likely to lower the mortality rate from cancer and help us find parking spaces, the larger picture appears increasingly gloomy. Climate change, ignored by many politicians, threatens our way of life. Our fever for resources causes artificial earthquakes, poisoned rivers, and flammable drinking water. Astonishing advances in technology have been used against us to create a nearly omnipotent surveillance state. Industry wields immense power over our government, and the growing gulf between the rich and the poor shows no sign of easing. Corruption, pollution, and inequality were no strangers to 1915, but that which promised to improve life at the PPIE is cause for much concern today.

If the PPIE really was defined by sincere optimism, there was a naïveté to that earnestness. Utopianism is always problematic, but especially so when corporate sponsors are involved. Two photographs in City Rising best illustrate the divide between utopianism and marketing. One shows the destruction of the Italian Tower after the fair closed. The tower crashes to the ground as spectators watch. Like most structures in the exposition, the tower was meant to be temporary. And yet prior to the fair, Harbor View housed “earthquake shacks”; the tenants, almost entirely poor and working-class, were forced to vacate without compensation. It must have been a cruel sight had any of these individuals seen the plaster prop buildings razed.

Another building is seen as it was hauled out to sea, on its way to a new home in San Mateo. These days, one doesn’t need to build fake cities or move buildings in order to sell safety razors. Nor does one need to travel thousands of miles to witness the latest technology and experience curiosa. This is not to lament the loss of shared cultural experiences, of which there are many, both corporeal and virtual. The motivations behind the exposition, good and bad, are still with us, but the form, and possibly spirit, of the fair is unique to a time that is long past.

‘City Rising: San Francisco and the 1915 World’s Fair’ runs through Dec. 6, 2015 at the California Historical Society in San Francisco. Details and more information here.