In a 1955 review of Ruth Asawa’s gossamer hanging wire sculptures at Peridot Gallery in New York, Time magazine identified the San Francisco artist as a “housewife and mother,” and reduced a sensibility drawing on Mexican weaving techniques, Great Depression-era material economy and a Black Mountain College education to “Oriental.” The article was intended to be favorable, marking the arrival of an exciting young modernist, yet it heralded Asawa alongside fellow Japanese American sculptor Isamu Noguchi under the cringe headline “Eastern Yeast.”

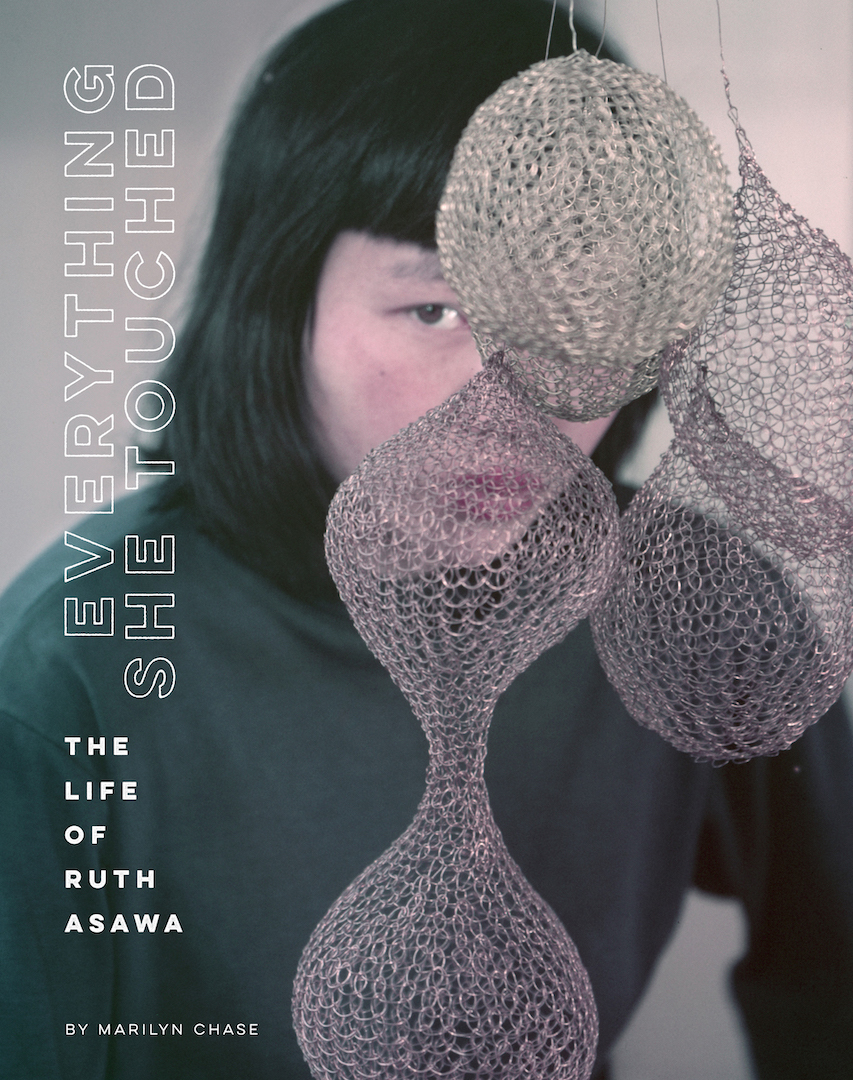

It was not the only backhanded compliment Asawa’s biomorphic abstractions, which rendered metal filament as mesh ovals, often nesting one shape within another, garnered from well-meaning critics. Some commended her art while calling it mere craft, others saw little besides feminine, womblike forms. “Far east” cliches abounded. Added to essentialist assumptions about a woman of Japanese heritage was coastal chauvinism: Asawa’s departure from Peridot in the early 1960s left her without New York representation for most of her life.

Throughout her life, when one door closed, Asawa opened another. She learned perspective from Disney illustrators interned at the same California concentration camp as her family during World War II. Refused a teaching credential due to racism, Asawa absorbed the experimental pedagogy of Black Mountain College, acquiring lifelong mentors in abstract expressionist Josef Albers and architect Buckminster Fuller. Snubbed by New York, Asawa redoubled her commitment to San Francisco, transforming public arts education and the region’s built environment.

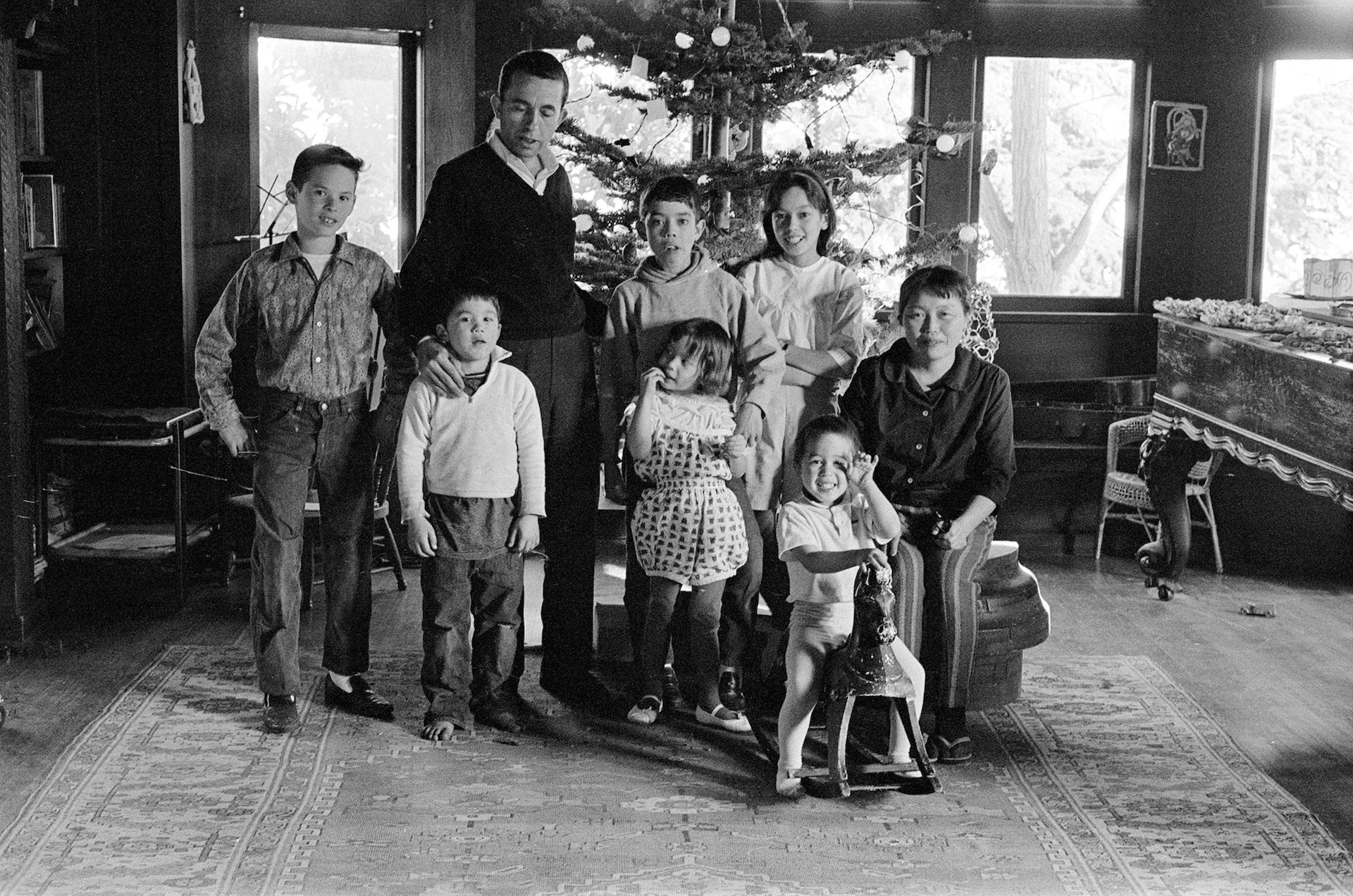

Everything She Touched: The Life of Ruth Asawa (Chronicle Books), the first comprehensive biography of Asawa, who died in 2013 at the age of 87, reveals the emotional life and personal trials of a social pathbreaker and civic leader who avoided memoir and political outspokenness. Author Marilyn Chase, a San Francisco journalist and teacher, connects the barbed wire and dispossession of Asawa’s early life to the artist’s transformative approach to spooled metal, and intimately conveys the teeming creative life inside her home studio as it filled with six children. The most pronounced through line is Asawa’s deliberately interwoven family and art practice.

The well-designed book features medium-format photography by Asawa’s close friend Imogen Cunningham. There’s installation shots, highlighting her sculptures’ undulating shadows, and pictures of Asawa laying on the ground among her kids, reaching her bandaged fingers into forming teardrops. Other imagery includes Asawa’s drawing-laden correspondence with her then-fiancé Albert Lanier, the architect and preservationist. Chase draws on original interviews and Asawa’s papers at Stanford, including granular accounts of her feverish struggle against lupus, and quotes heavily from the couple’s epistolary courtship, which the family provided.

Remarkable in the letters, once thought to be destroyed, is not only the couple’s candid view of their respective families’ discomfort with the inter-racial marriage, and the stigma they would face even in enlightened San Francisco, but also Asawa’s clear articulation of her long-term desires. She repeatedly urges Lanier to love her as much as his work, and to expect her to do the same. “There’s so many voices in the letters,” Chase said in an interview. “Artistic voices, erotic voices, reverence for their teachers, heartbreaking discussions about helping their parents understand their commitment to each other—regardless of society’s opposition.”

Asawa was raised on a farm in Norwalk, now part of Los Angeles County, until the United States entered into World War II. The injustice of her family’s internment is a specter throughout the book. In her journal, she marked the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki with what Chase calls a “laconic” note: “While in Mexico, the Japanese surrendered.” She used “colored” bathrooms in the Jim Crow South, and even at Black Mountain initially ate meals with staff in the kitchen. Chase found no trace of Asawa discussing the war with Albers, who left Germany after the Nazis closed the Bauhaus school; her children only learned parts of her wartime experience in the 1990s, helping her forge the bronze Japanese American Internment Memorial in San Jose.

One of the most vindicating storylines is Asawa’s arts education advocacy. She brought the idea that working artists are best poised to teach art from Black Mountain to San Francisco, and through careful observation of local politics and wealthy patrons—she was known for sketching city officials at meetings—created the public arts high school that now bears her name. She was at the forefront of many other trends now taken for granted: Reusing materials, farm to table dining, the false binary of arts and crafts. But other causes remain woefully unresolved: The few gains made in public arts funding since the Great Recession are being erased as the economy spirals, and wanting artists to financially partake in their work’s resale value still seems like a long shot.

Asawa has long been something of a household name in the Bay Area, and the biography recounts the physical toil and political maneuvering behind her many iconic public art commissions. But Chase reminds readers Asawa’s national stature, exemplified lately by signature postage stamps, wasn’t assured. Jonathan Laib, the New York curator, wasn’t familiar with Asawa when her children approached him about selling an Albers canvas to support her end-of-life care in the late 2000s. His advocacy—including shifting the nagging perception of her fine art sculptures as design objects—helped propel her work’s value to the stratosphere in the years before her death, and today she’s represented by the powerhouse David Zwirner gallery.

Yet Asawa received another sendoff, one more aptly reflecting her values and restless spirit. Her son Paul mixed her ashes with those of Lanier and their son Adam and created from them ceramic works for his siblings. As Chase writes, “Ruth made sure her earthly matter was not destroyed but rather transformed until, in the end, Ruth Asawa herself became a work of art.”