Existe lo que tiene nombre: Contemporary Photography in Mexico, a two-part exhibition at SF Camerawork and Galería de la Raza, brings together twenty-two photographers working across Mexico today. The artists, born mostly between the mid-1970s and the early-1990s, represent a range of emerging and established artists working in differing styles, including documentary, landscape and conceptual photography. There is no single theme or aesthetic that blankets Existe lo que tiene nombre, which translates to “it exists if it has a name”; instead, the exhibition is akin to a collection of loosely related – and highly engaging – stories.

Alejandra Laviada began photographing Mexico City’s modernist Hotel Bamer in 2006, shortly after it closed. Her Hotel Bamer series, on view at SF Camerawork, captures a place abandoned in haste, the vestiges of former lives still present. There is a similarity between Laviada’s work and photographs of Chernobyl or British Columbia’s Kitsault mining town, where shopping carts sit idly in empty grocery stores. One of Laviada’s photographs shows five mattresses in varying states of decay. They stand upright in an empty wood-paneled room, on a crimson shag carpet you can almost feel. The mattresses’ stains and frayed corners allude to years of family vacations, honeymoons and business trips.

Viewing pictures of Chernobyl or Kitsault today is a form of time travel – the locations are frozen as they were decades ago. Even though Laviada’s photographs convey a similar impression, Hotel Bamer’s furnishings were ‘retro’ well into the 21st century. Her photographs are both nostalgic and contemporary, documenting a type of mid-century hospitality that may have persisted indefinitely, as style and taste shifted outside its walls.

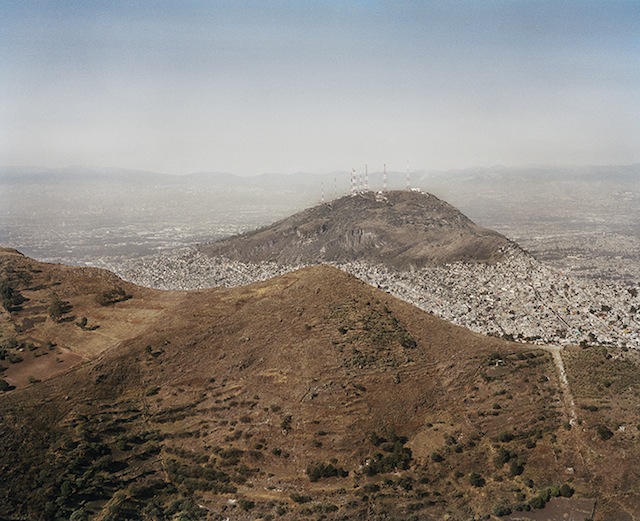

While many works in the exhibition could be described as vignettes, Pablo López Luz’s two large photographs at SF Camerawork are something more epic. The pieces, View of Mexico City (2013), are urban landscapes taken from one of the city’s many hills. In one image, the view is not unlike that of Bernal Hill and its modest microwave tower, as seen from Corona Heights.

The density of this megacity is awesome, and Luz’s cloudy image is less likely an aesthetic treatment than proof of actual pollution. Luz is interested in what landscape can disclose about social life without actually picturing people. These photographs record a landscape entwined with politics; the breathtaking scenes point to serious ecological and social concerns.

Livia Corona Benjamin presents work at Galería de la Raza that shares López’s concerns with urban development. Her series Two Million Homes for Mexico (2006-15) looks at the explosive construction of low-income housing in rural areas during former president Vicente Fox’s term. 47,547 Homes. Ixtapaluca, Mexico (2011) shows a sea of identical orange and beige homes stretching across a valley. Though tiny people can be seen on the streets outside the development, the community doesn’t look inhabited; the rows of houses are orderly and sterile. As a result, the grid of sameness resembles a model more than a life-sized city.

A photograph from the same series shows a family inside one such house. A man and woman sit on a couch, facing the camera, a younger woman sits on the stairs above them. The subjects bear the awkward and slightly uncomfortable faces of people sitting for a contemporary art project. The house appears narrow and small; its occupants fill the photograph and leave room for little else. Small hints at their personalities emerge from decorating cues: a large ceramic frog, a turtle-shaped planter and a glass cabinet in the hall. The image grounds and humanizes the mostly uniform landscape in 47,547 Homes. Ixtapaluca, Mexico, without narrowly describing the lives of its residents.

Other artists in the exhibition tell stories that unfold through subject studies. Like the United States, Mexico is gripped by staggering income inequality and a culture of affluence surrounding the upper crust. Yvonne Venegas, originally from Tijuana but now based in Mexico City, addresses this culture in a series of photographs. She focuses on the denizens of San Pedro Garza García, a wealthy suburb of Monterrey in northern Mexico, exploring how individuals project social status and celebrity.

In Loretto in Studio (2013), Venegas captures a family in a photography studio as they prepare to have their portrait taken. Two infants in long white dresses draw the attention of the family members. The women are partially obscured, but their dresses and impeccable hair suggest high social status, or the desire to emulate it. This moment of preparation is not particularly notable, but the accumulation of such ordinary scenes (a couple entertaining guests, a family sitting solemnly around a table) documents the rituals necessary to affirm and preserve the appearance of wealth.

Jimena Camou and Juan Carlos Coppel’s work (at Galería de la Raza and SF Camerawork, respectively) is cinematic verging on fiction. Alternately, David Vera’s conceptual project Sweetbook (2014), on view at SF Camerawork, is highly personal, grounded in his father’s illness and vision loss. Other artists work with video or politically charged photographs.

Viewers may relate to some of the narrative threads in the exhibition, which include nostalgia, urbanization and the trappings of wealth – these subjects are not unique to Mexico. Other experiences and political issues may be unfamiliar to some Bay Area audiences. While each of the artists in Existe lo que tiene nombre takes a different approach to storytelling, all have compelling stories to tell, be they mysterious, fractured or unfinished. Through photography, they name things – events, memories and ideas – pointing to their existence and providing access to the unfamiliar.