To launch the July 23 public opening of by Alison Knowles, the retrospective at the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archives (BAMPFA) covering 62 years of the artist’s production, visitors were invited to participate in the latest revival of Celebration Red (1962–present), one of the most well-known of Knowles’ event scores. Participants placed a single red object they brought with them in each square of a grid laid out on the floor of the museum’s amphitheater-styled atrium space.

During the performance, a certain informality prevailed. Participants and observers alike milled about and hovered at the edge of the work. Knowles sat in the front row, surrounded by family members, friends, old classmates, and fans. The hum of small-group conversations rose and fell. All the while, objects appeared: ten Solo beer cups, a red beret, an inflated beach ball, a Target shopping bag, a bobbing wooden toy, a polka-dot birthday hat, a pair of fuzzy dice, and a lock of red hair cut with a pair of red scissors, to name a few. One woman outstretched her hand and dropped an unidentified (from my vantage point) object to the floor. Dissatisfied with its placement, she nudged it to the center of the square.

This unscripted, barely observed moment in a sequence of similar ones nevertheless encapsulated a resonant tension that prevails throughout Knowles’ oeuvre: what it means as an artist to create the potential for an artwork and not the work itself. She authors the underlying composition, rhythm, or structure and sets the piece in motion. She leaves the outcome to chance, and our attention is focused on that outcome. But her attention lies at the juncture between the possible and the realized, at the point where intention leaves off and knowing begins.

This tension is present from the very beginning of her engagement with the Fluxus movement, which represented a radical break with art production of the mid-20th century. (The show takes up the two front galleries of the museum’s lower level. A rear gallery features Fluxus-related work from BAMPFA’s permanent collection and offers more context for the movement’s influence on Bay Area conceptual art.) Fluxus engulfed composers, poets, visual artists, architects, designers, and publishers in experimental, cross-disciplinary practices that emphasized process over a finished work. With Fluxus, meaning arises from the uncertainty of and variance within actions rather than a concrete object.

Fluxus artists and composers participated in festivals (Fluxfests), designed scores for participatory performances that lent themselves to wide interpretation, created Fluxkits to distribute these scores, and published chapbooks of Fluxus poetry that prioritized typographical elements and composition over textual meaning. Included in a 1965 Fluxkit is an early work in the retrospective, Bean Rolls (1963), in which Knowles placed beans in a can alongside rolled up scrolls of text with information she researched about beans.

Beans became a recurring motif throughout her career. A pair of works from 2000, Bean Turner, Coral, and Bean Turner, Brown, are also included in the show. They represent another exploration into the tension between finitude and potentiality. Elongated, crumpled sculptures made from hand-crafted flax paper filled with beans, they produce a satisfying, echoing rattle when turned over and the beans cascade down their length. Like any instrument, the sound has its own unpredictable existence separate from the object that produced it. It challenges the limits of what constitutes the work and what we expect from it.

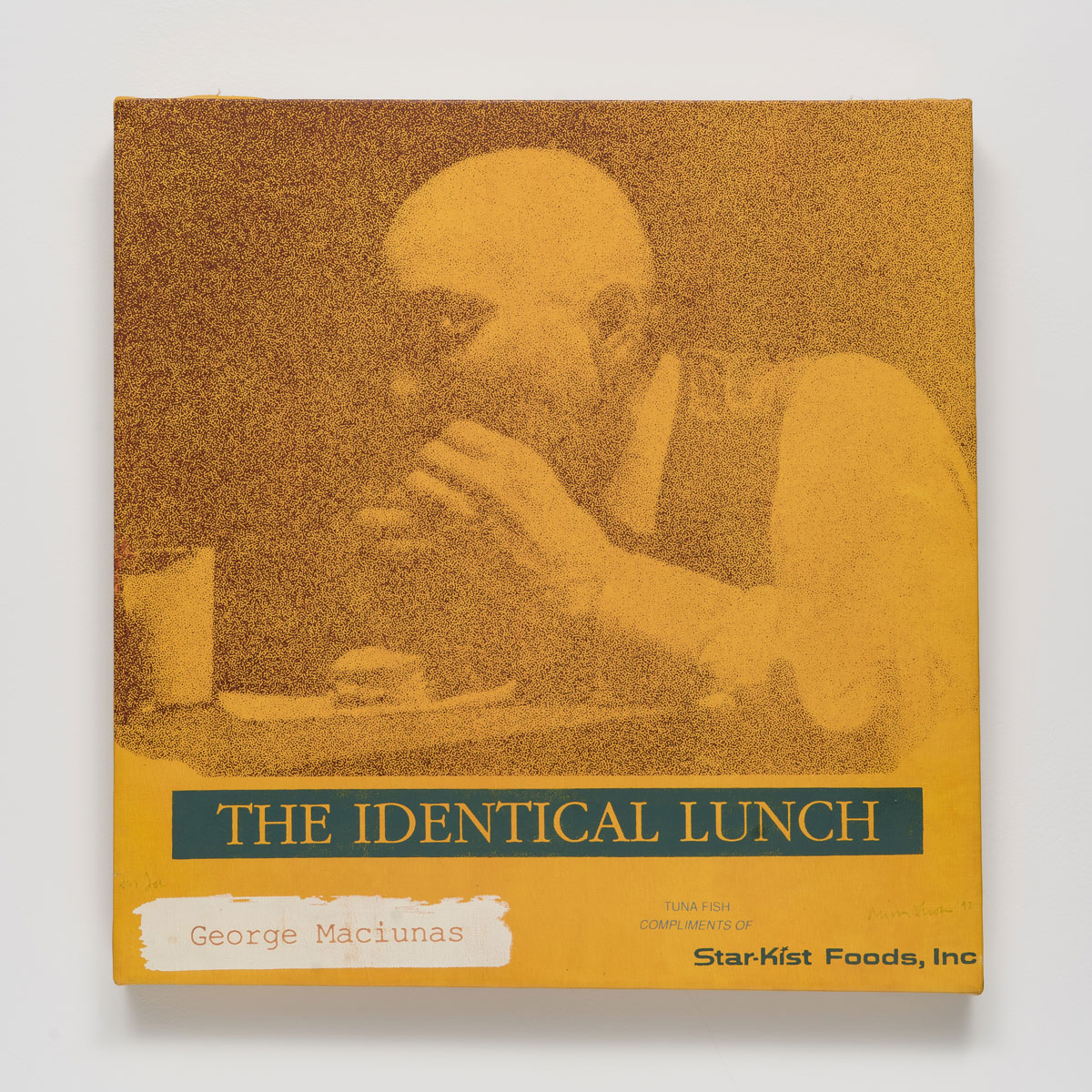

Even in the early disruptive days of her Fluxus-related practice, Knowles retained the transformational power that we ascribe to art, as evidenced in other food-related event scores, notably Make a Salad and The Identical Lunch. Documentation of both are well-represented at BAMPFA. In each, the self-evident and ordinary ingredients such as lettuce or a tuna-fish sandwich become the scaffolding through which one could see and hear the world anew. She elevates everyday actions familiar to anyone into rituals infused with symbolic meaning. We literally consume and complete her scores, carrying forward her intentions in our own bodies.

Knowles is best known as the only female co-founder of Fluxus. But it is the concept of the “transenvironment” that she coined with the creation of The Big Book (1966) that also places her in an alternative trajectory of conceptual art. The Big Book, which longer exists, was an eight-foot-tall sculpture composed of illustrated “pages” erected along a central spine that one could walk amongst, in or out of, or even over. “Transenvironment” was the term she used to describe an alteration of perception that occurs within an environment, a perceptible shift of awareness and context, a “rupture … [and] radical transstructuring of texture and text” as she noted in a 1982 conversation with George Quasha, included in the retrospective catalog.

In this conversation, she empowers text with the self-reflexive capacity “to tell you what to think, what to think about it, what not to think.” She also imbues text with a command over space and movement, noting that “it can at any moment cause a rupture in the plane of reading.” A significant example of this command is the 1983 performative sculpture, Loose Pages, in which the performer literally embodies the idea of a book, becoming the spine as Knowles drapes pages over limbs and trunk.

To associate this transformational power to text places her conceptually and historically alongside later artists such as Vito Acconci, whose forays into concrete poetry foregrounded reading as a performative act, and Robert Smithson, for whom meaning arose from the materiality of text. Each artist invites audiences to become aware through a navigation around and collision with text, moving across the page, moving through and around the shape of words.

With this in mind, one can approach by Alison Knowles as a reader rather than visitor, especially since the exhibition is heavy on photo documentation, wall text, and material placed in vitrines, which produces a second-hand accounting of her work and obscures some of her sly humor. Our distanced vantage point is unavoidable given the performative nature of much of Knowles’ career, with its emphasis on the ephemeral, incidental, and impermanent.

To approach this exhibition as text, though, is to engage with how radically Knowles used participatory gestures to shift our perceptions of authorship. A material object cannot be untethered from the artist; its act of creation is always present in the physical evidence before our eyes. Text, however, begins its life with its author, but the longest phase of its existence resides with its readers, no matter what form that text takes: a book, a sculpture, a can of beans.

In the act of reading, the visible structure is the means through which one sees into the unknown and is willingly transformed by this seeing. In six-plus decades of inviting us to take up ordinary gestures and chance encounters with her, Knowles has merrily led us past a sense of certitude into moments of incidental and unexpected beauty. Where she leaves off, our knowing begins.

‘by Alison Knowles: A Retrospective (1960–2022)’ is on view at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive through Feb. 12, 2023. Details here.