It’s evident from the very start that the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s Joan Brown retrospective is going to be a bit different. It could have something to do with the painted walls that greet you off the seventh-floor elevator (peach and bright orange). It could be the deliciously unhinged wall text next to Joan + Donald, a 1982 painting of Brown holding a squirming tabby cat. (Hint: it involves declaring the cat a tax write-off and an IRS audit, no spoilers here.) But really it’s just the fact that this is a Joan Brown show, and Joan Brown was a singular artist.

Curated by SFMOMA’s Janet Bishop and Nancy Lim, this retrospective is the late San Francisco artist’s first in over 20 years. Following Brown’s career from her art school days at the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute) to her untimely death at the age of 52, the show moves fluidly through Brown’s evolving style and subject matter. The extended pieces of wall text are full of delightful autobiographical details and images of Brown’s own paint-covered visual references.

It’s hard to believe, looking at her assured, large-scale figurative paintings, that Brown almost didn’t become an artist. She applied to CSFA — with a portfolio of drawings of movie stars — on the eve of her enrollment at an all-girls Catholic college. And she did not transition to art school easily. On the verge of dropping out after one year (her prim mother, aghast at the nude models, would have rejoiced), she took a summer painting course with Elmer Bischoff, who became a lifelong mentor and friend.

Bischoff encouraged Brown to paint the stuff of everyday life, teaching her to trust her own instincts above art world fads and critical responses (a lesson that would serve her well in the next three decades). In that class, Brown learned to love paint. Her pieces from those early years are thickly impastoed; some look like they could still be wet. Comically large brushes were involved — sometimes even trowels — as Brown layered large swaths of house paint in swirling images of women swimming; her son under a heavily decorated Christmas tree; dogs; her domestic space; and a Thanksgiving turkey.

Brown found remarkable and rapid success early in her career. Painted in 1959, that aforementioned turkey was purchased by the Museum of Modern Art in New York when Brown was only 22 years old. By 1964, her work had appeared on the cover of Artforum (the accompanying article dubbed her “Everybody’s Darling”), in group exhibitions at the Whitney, the San Francisco Museum of Art (now SFMOMA), and in two successful solo exhibitions with New York’s Staempfli Gallery. But she was disenchanted with her heavy brushwork, and, trusting her instincts, she decided to pursue a new direction in her work, refusing gallery shows for the next three years.

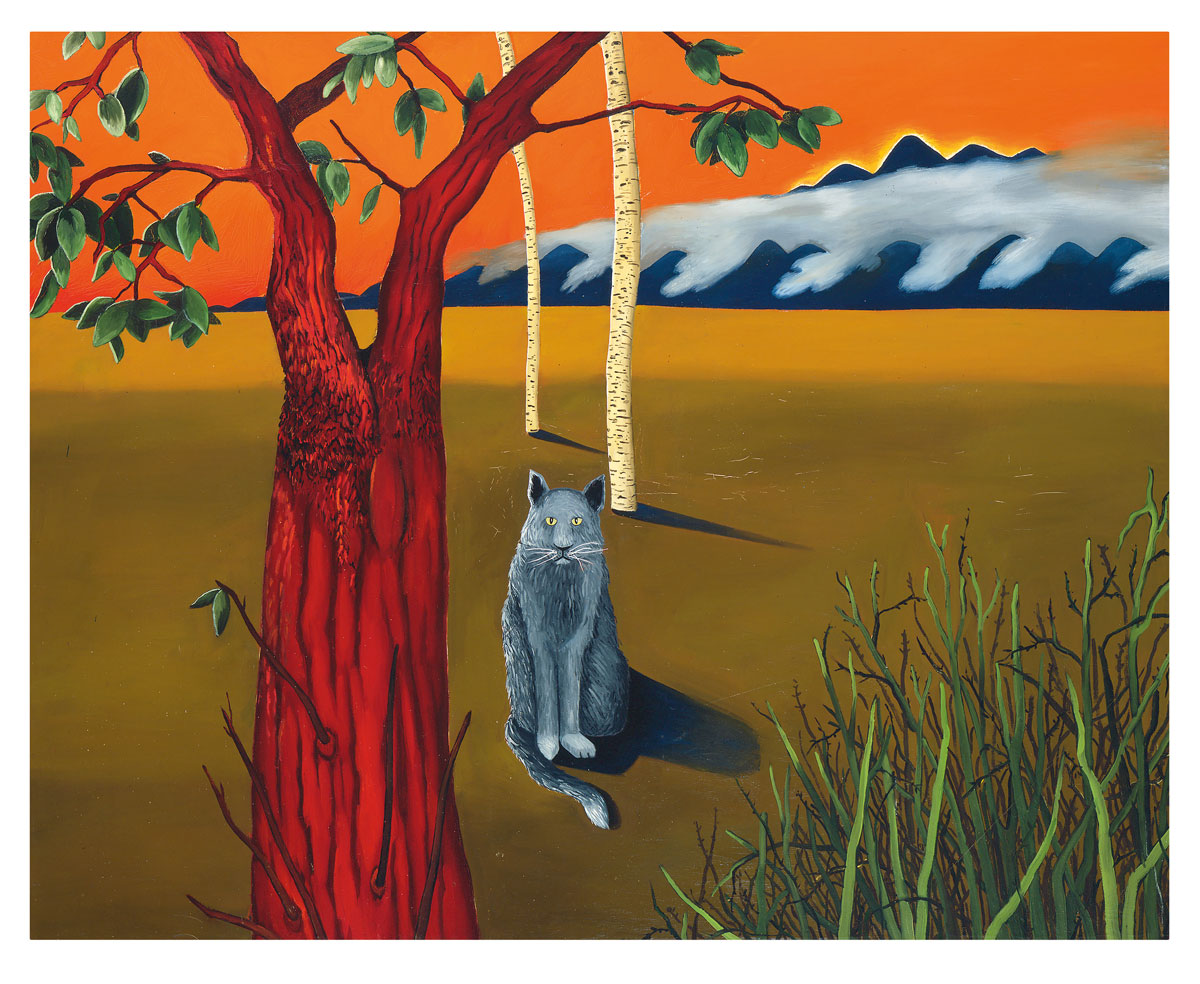

In the SFMOMA retrospective, this shift comes suddenly, via Gray Cat with Madrone and Birch Trees (1968), a large-scale canvas that references Henri Rousseau’s tropical landscapes. In comparison to her earlier work, this painting’s surface is nearly flat, its subjects rendered distinctly; a large gray cat stares out from a spare landscape of olive and ochre, topped by a nuclear orange sky. This is a deeply weird painting, a portal to another way of rendering Brown’s view of the world.

While her subject matter would shift over the next two decades (except for animals, a steady constant) — to frank self-portraits, dancers, swimmers and spiritual concerns — Brown’s departure in style was complete. Things would get only more pared-down and direct from here, as figures became silhouettes and outlines, and settings became opportunities to revel in retina-zinging color combinations or dynamic repeated patterns.

In the show’s center, work informed by Brown’s love for open-water swimming occupies an entire gallery. Three contemplative self-portraits depict Brown before and after an attempt to complete the first all-women’s swim from Alcatraz Island to Aquatic Park in 1975 (a passing freighter created disorienting 13-foot waves). These paintings tell the story of that traumatic swim at a remove: in some, Brown wears a freighter pattern on her dress; in others, the chaotic scene is depicted as a painting within the painting.

This is a regular Brown motif, often used to cite art historical antecedents. In The Search (1977), she paints herself in a diaphanous purple dress, working on a painting of Nofret, a princess from Egypt’s Fourth Dynasty. Here and in other self-portraits, Brown stares out from the canvas blank-faced, letting details like a dripping brush emphasize her identity as a painter.

The final years of Brown’s life were marked by a turn towards New Age spirituality, with a focus on the teachings of Indian guru Sathya Sai Baba. Self-portraiture became a path towards self-knowledge and transcendence, and Brown painted herself alongside constellations, occult theosophical symbols and the Chinese zodiac.

In the fantastic exhibition catalog, art historian Marci Kwon’s essay examines Brown’s use of non-Western art as a source material. Searching for commonalities between Chinese, Egyptian, Indian, Maya and Aztec imagery, Kwon writes, “Brown endeavored to paint this mystical world without difference, and yet her work teems with moments in which difference is not only present but intensified.” (At SFMOMA, for instance, paintings including Chinese and Sanskrit text are written incorrectly or with extra flourishes, turning Brown’s attempts at universality into decoration.)

Brown died, along with two assistants, in 1990 at the age of 52 from a tower collapse while installing an obelisk at Sai Baba’s Eternal Heritage Museum in Puttaparthi, India. And while she held great disdain for art critics and art historians, I wonder how she might have absorbed critical thoughts on her work had she lived to make more of it. Brown’s view of the world, once she passed through that colorful, flattened portal, had her at its center — often quite literally. But in her idiosyncratic style and her steadfast trust in her own instincts, she created a model for what it can look like to make art on one’s own terms, and toward one’s own end.

‘Joan Brown’ is on view at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Nov. 19, 2023–March 12, 2023. Details here.