Secondhand, the first new exhibition to open at Pier 24 Photography in San Francisco since July 2013, presents the work of over a dozen artists whose practice relies on the appropriation of pre-existing photographs. Paired with vernacular photos from the Pilara Foundation collection (the folks behind Pier 24), Secondhand is more than a survey of a particular artistic technique; it offers a glimpse at the varied relationships between people and photographs.

The found photography collections of Amsterdam-based publisher Erik Kessels, which are given several large installations, set an important tone for the exhibition. The gallery devoted to Kessels’ ongoing series of books, in almost every picture, is particularly salient in light of critiques that younger generations’ relationship with photography is self-absorbed and obsessive.

In almost every picture #1 (2002) is a selection of several enlarged amateur photos of a woman in stereotypical tourist poses, with monuments, mountains, and other envy-inducing settings behind her. The photos on display are a handful of the hundreds of snapshots taken by the woman’s husband between 1956 and 1968. This collection documents the familiar impulse to catalogue memories and boast about exotic exploits. For better or worse, a photo-happy spring-breaker with an iPhone and an Instagram account may be paying homage to his grandparents’ school of photography rather than indulging in newfangled narcissism, as many Baby Boom and Gen X journalists argue. This retro behavior was probably learned through endless slideshows of the Grand Canyon and by spending much of his childhood saying “cheese.”

Works from Kessels’ book Album Beauty (2012) are represented in a Lewis Carroll-esque gallery, in which larger-than-life images from found photo albums adorn the walls and foam core cutouts. Viewers may feel as if they’ve been shrunk down and must navigate their way through an old family album filled with unfamiliar faces. These otherwise anonymous subjects are given a level of import due to their inflated size, calling attention to the significance of everyday photography.

The installation also includes a large selection of framed photos that are blemished by stains, double exposure, and wayward thumbs. Surrounded by the acceptable photos that made the final cut in their original albums, this photographic detritus makes visible the efforts to produce archive-worthy memories.

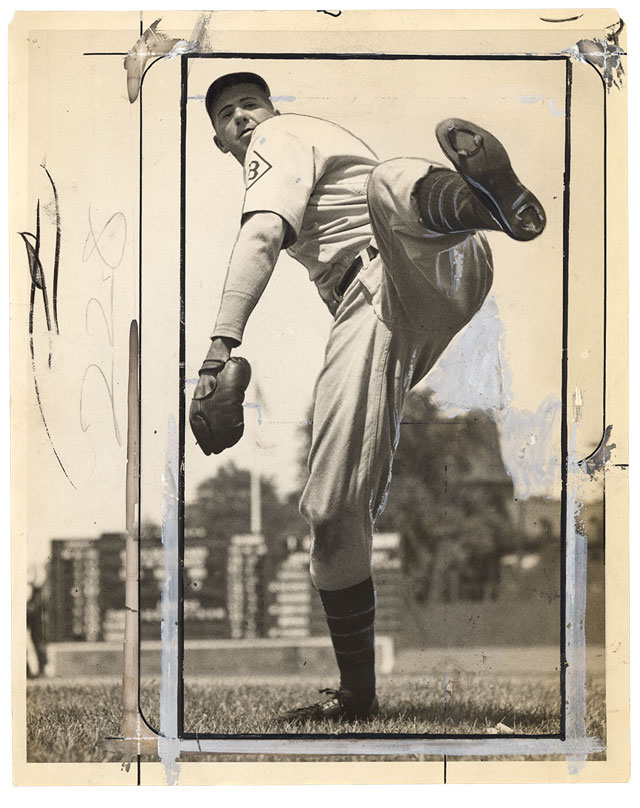

As with Album Beauty, a series of baseball press photos from the Baltimore Sun archive shines light on the process of creating the images seen every day. The black and white action shots of baseball players on the mound and at bat are scrawled with lines and notations instructing editors how to present the images. These markings, like the decisions of all photographers and editors, make judgements about what is important and worth reproducing and preserving.

Berlin-based photographer Viktoria Binschtok is one of several artists in Secondhand who engages with digital imagery. Binschtok photographs locations in New York City she has found on Google Street View, exhibiting her work alongside corresponding prints of screenshots from Street View. She does not rephotograph the scenes found online, but creates an entirely new image, focusing on what is unseen or obscured by Street View. In one pairing, the unremarkable street in front of a diner is juxtaposed with Binschtok’s lonely yet inviting image of a cherry red diner booth bathed in light.

Binschtok’s photographs call out the ignorance that is embedded in the seeming omniscience of Street View, offering an alternate vision of the faux-objectivity of software. As someone who spends hours every week on Street View — obsessively anticipating road trips — I find Binschtok’s work comforting. She puts to rest my worries about spoiling the surprise of a new location. I’m reminded of the inevitable joy and discovery that can be found in any location, regardless of what one already knows about the place.

Binschtok’s photographs, of course, are no more authoritative than Google’s. Though beautifully composed, her shot of the diner booth might conceal a couple that broke up while eating there or a desperate customer who spent her last dollar on a cup of watered-down coffee. Binschtok’s aestheticization of sterile Street View scenes is only one interpretation of those sites, but her photos are also reminders of the innumerable interpretations that are possible.

Rashid Rana, regarded as one of Pakistan’s most important contemporary artists, exhibits several large scale collages that, like Album Beauty, create a bodily experience in viewers. Two of the works on view comprise thousands of disjointed images of protests found online. Fused together, these images create a composite protest, generic but evocative. The details of the faces of the individuals are eclipsed by the totality of the composition, which washes over the viewer, creating a sense of tension and unease. Though far from a journalistic representation of a protest, these works possess the power to convey a corporeal and emotional truth about such an event.

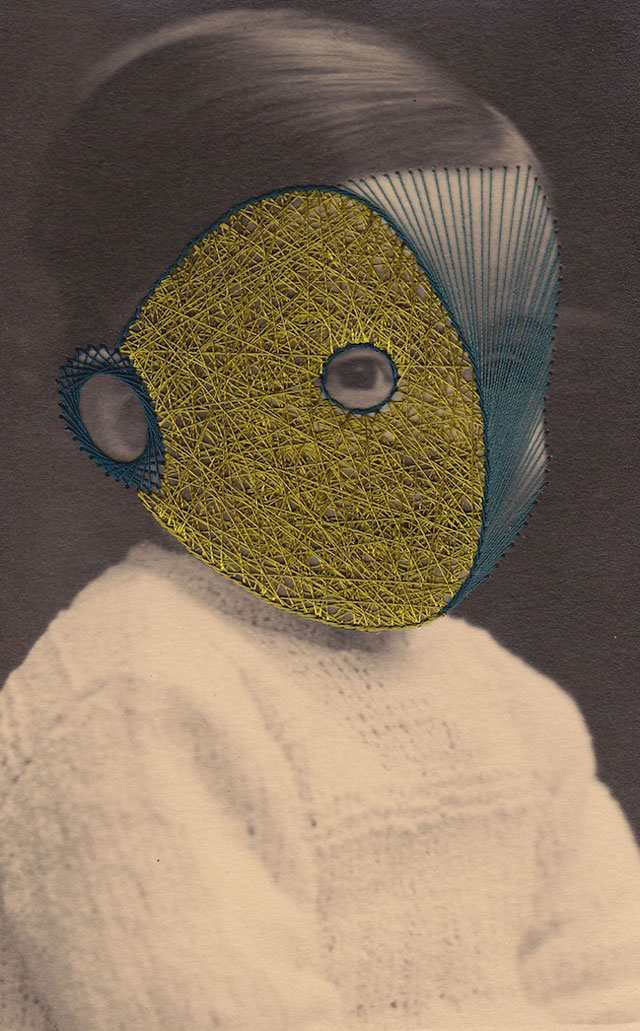

As it covers so much ground, Secondhand is well suited for Pier 24, which is considered the largest exhibition space for photography in the world. The forms of appropriation possible are as numerous as the emotions, questions, and conversations these works arouse. With Maurizio Anzeri, John Baldessari, Melissa Catanese, Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel, Hank Willis Thomas, and many other artists included, viewers can take any number of paths through Secondhand, drawing their own connections with the medium.

Secondhand runs through May 2015 at Pier 24 Photography in San Francisco. For more information visit pier24.org.