In Isaac Julien’s thrilling show, I Dream a World at the de Young, the shifting images on gallery screens seem to respond to one another with something approaching sentience. If montage is the language that film uses to communicate things like character, plot and emotion to us, then Julien’s elaborate video pieces speak in a cinematic language I’ve never heard before.

While most directors attempt to use the language of montage to tell a story roughly analogous to a novel, installation artists like Julien do something else entirely. The word “poem” comes to mind to describe the British artist’s work, but “fractal” is perhaps more fitting; Julien’s large-scale video projections get deeper and more complex the further you move through them. Images, words, sounds, colors and themes reproduce themselves across the multiple screens of Julien’s installation pieces, sending the eye ricocheting around in an effort to take it all in.

The de Young’s show, on view through July 13, 2025, is a buffet of six video installations that very compellingly explores questions around Black and queer experiences, visual culture and the history of otherness. Given the larger political situation in which the show takes place, it feels urgent and necessary. At a time when overwrought and absurdly illogical denunciations of “DEI” are used to stifle free thought, I Dream a World shows just why deep contemplation and real empathy are essential to unraveling the thorny questions at the heart of the American project.

Watching one of Julien’s installation pieces tends to feel absorbing and cumulative, as though the work is teaching you how to watch it as you go along. It can also feel exuberant and even overwhelming — part of Julien’s aesthetic is to give a viewer far more than can be seen with just two human eyeballs. In fact, his pieces Ten Thousand Waves and Once Again . . . (Statues Never Die) arrange their many screens in such a way that it’s not physically possible to take everything in from a single vantage point. Viewers must navigate their way around the screening space, making choices about where to stand and look.

In spite of these formal devices that impose a degree of effort onto viewers, the installations in I Dream a World do not feel opaque or off-puttingly abstract. Visually and emotionally stimulating, they offer multiple points of entry. It’s possible to walk right into the middle of a screening and quickly become immersed. (This is one of the benefits of pursuing fractal cinema over narrative.)

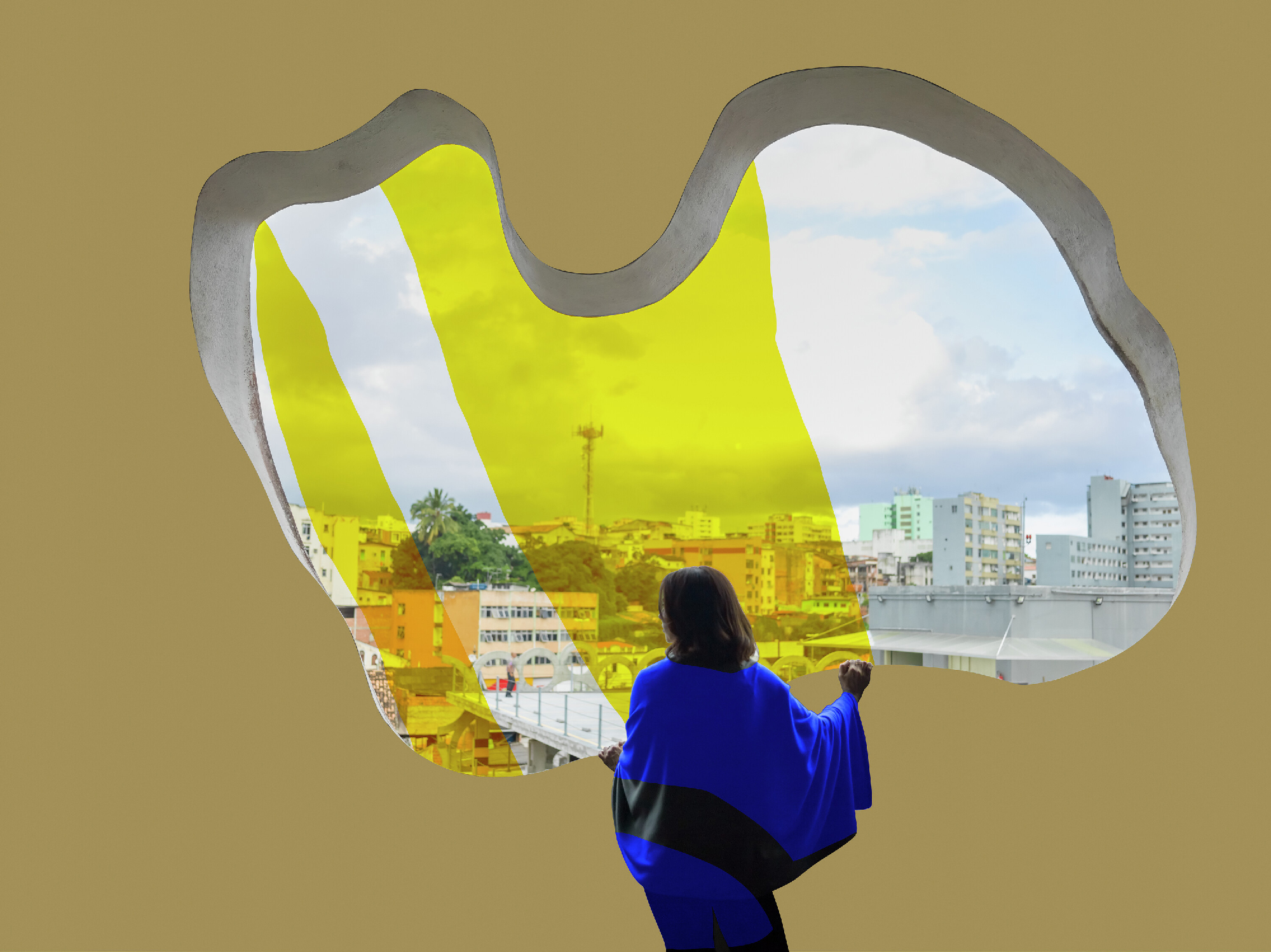

Frequently Julien’s screens seem to interact, bouncing ideas and images off of one another, moving in sync (then de-syncing), echoing slightly different versions of things around the gallery, establishing their unique rhythms and pulses. In a particularly electric moment from A Marvellous Entanglement, about the life and work of the radical Brazilian architect Lina Bo Bardi, the rightmost screen shows an older version of Bardi while the leftmost screen shows a youthful version, the center screen wandering through one of her buildings. In an elegant syncopation, the younger Bardi echoes the words of the older Bardi at a slight delay, bringing to mind questions about how age and appearance affect how we hear what someone says.

Like any good creative genius, Julien has mapped out his own personal constellation of fellow intellectuals and creators, ranging from high art to pop culture. He is clearly fascinated by prominent thinkers and big ideas, bringing them to life by hiring top-name acting talent to embody such figures as Frederick Douglass or the aforementioned Bardi. The result can often have elements of a mainstream film, even as Julien creates scenes and splices together visuals in ways few filmmakers can.

His piece Once Again . . . (Statues Never Die) rings out with references to Aristotle while staging a kind of conversation between Black philosopher Alain Locke and American art collector Albert Barnes. In early-20th century New York, the two men debated ideas about the place of Black art in America.

Art museums frequently pop up in Julien’s wide-ranging montages, including in-depth wanderings through the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore and the Barnes Collection in Philadelphia. There are references to Robert De Niro in Taxi Driver, the major Black silent film Within Our Gates, and the transformational Blaxploitation film Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song.

As heady and intellectual as Julien’s installations may be, they deliver simple beauty and visceral emotion. Walking into Lessons of the Hour, which traces episodes in the life of Frederick Douglass, the installation’s 10 screens immediately envelop a viewer in a mosaic of a Virginia forest turning gold during the months of fall.

The montage is breathtaking; the screens’ combination of close-up and wide-angle shots evokes the feeling of being within the forest. During Once Again . . . (Statues Never Die), Locke, who is played by Moonlight co-star André Holland, turns a loving gaze to the eyes of a statue, a moment sure to evoke an emotional response in a viewer.

Yet Julien also has a penchant for piercing the serenity that his works often conjure. Amid the beauty of the fall forest in Lessons of the Hour, Julien drops in a shot of two hanging Black feet from Within Our Gates, taken from the 1920 movie’s infamous lynching scene. It immediately draws the eye for being the only black-and-white-shot amid nine other screens of gorgeous fall colors, as well as for the discordant image of a lynched Black person in what was just moments ago a scene of complete pastoral tranquility.

Curator Claudia Schmuckli has elegantly staged I Dream a World, providing a central atrium where visitors can read the wall text for each piece and chart their own path through the exhibition. In a nice touch, she has placed screens at the entry to each exhibition hall, letting viewers see how much of the complete runtime has elapsed and providing a snapshot of what’s currently happening on-screen.

I Dream a World is an exhibition that requires large amounts of its audience’s time, and ideally multiple trips to the museum. If you were to watch all of the installations back-to-back, it would take about four-and-a-half hours to view them all. These works continue to develop and mature across multiple viewings, cross-germinating. I Dream a World really is a world unto itself — a capacious show, impressively intricate, offering a seemingly endless bounty of thought-provoking, emotionally rapt moments to its audiences.

‘Isaac Julien: I Dream a World’ is on view at the de Young through July 13, 2025.