When a colleague first suggested the Petaluma Arts Center host the works of Edgar Degas, the museum’s executive director Val Richman didn’t take him seriously.

“I just laughed,” she recalls.

She told me this story while standing in a small gallery hung with blue-matted, gold-framed originals from the French Impressionist — the result of good timing, personal connections and a sizable donor list.

Approach the museum from the south, and you’ll see a banner advertising the show in one of the Arts Center windows. It’s a definite contrast. Tucked between Traxx Bar & Grill and an industrial lot full of dump trucks, the terra-cotta colored building — a converted train depot — is pretty, but you wouldn’t expect it to hold the works of an artist also displayed at the Louvre.

Thematically, though, the display works well with its unexpected surroundings. Known best for his ballerinas, Degas was an exacting chronicler of physical exertion stretched to its limit, from nudes holding angular poses to taut-muscled dancers striking sharp arabesques.

But this exhibit of drawings, photographs and monotypes showcases lesser-known work, including self-portraits and renderings of Degas’ family and housekeeper. Along with undersung pieces by big-name contemporaries — Paul Cézanne, Mary Cassatt, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec — the Arts Center collection provides a softer, more warts-and-all look at the artist’s 19th-century Parisian circle, trading full forms for facial close-ups and poised ballerinas for frank depictions of what happened as they aged.

The collection belongs to Robert Flynn Johnson, the now-retired curator in charge of the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. And there’s actually a simple reason it’s not your typical arrangement of dancers and equine sport.

“It is an assemblage by a scholar acquired on a scholar’s income,” he writes in the exhibit’s accompanying booklet. “From the beginning I was aware that many important Degas works were simply beyond my means.”

But it’s also a testament to Flynn Johnson’s atypical taste. At a preview before opening weekend, the retired curator lead a tour explaining how he managed to buy each piece.

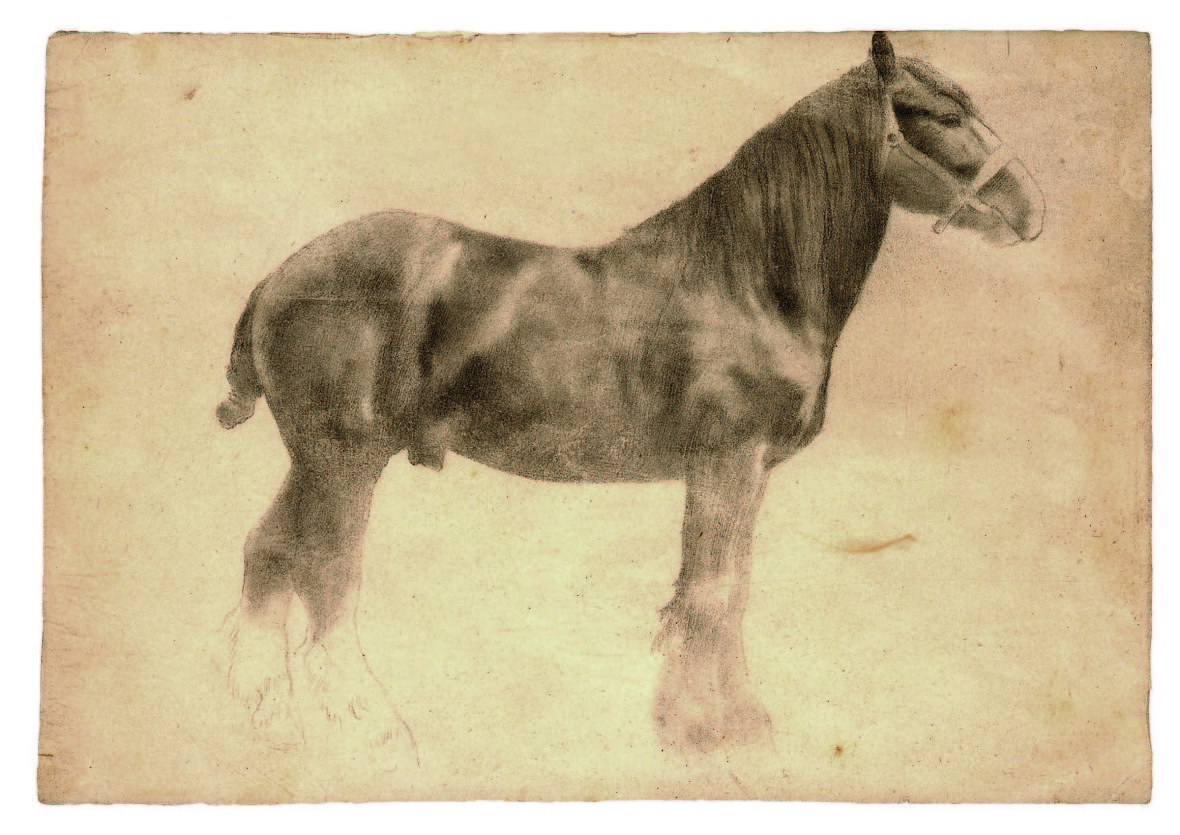

“People ask ‘How can you afford a horse?’” he said, stopping in front of an exquisite black-and-white drawing. “But it’s a Clydesdale. A lot of the snobby art collectors only want a racehorse.”

The same theme holds for other works — some of the female models are either middle-aged or have facial blemishes, thereby lowering their value. One Degas, Flynn Johnson’s first, is a small, black-and-white monotype of two trees. Monotypes were unfashionable among collectors when he bought it, he explains, and landscapes typically aren’t associated with Degas.

“Everything about the work I acquired in 1973 from David Tunick, a New York dealer, was wrong — except its beauty,” he writes in the exhibit’s booklet.

Degas’ more well-known work often appears to objectify its young and mostly female subjects. But some critics argue that the sexually ambiguous artist was less voyeur and more anthropologist, chronicling but not fetishizing the pretty brutalities of 19th-century ballet.

This small exhibit in Petaluma’s converted train depot helps build the latter case with nary a ballerina in sight. Through his drawings’ sharp lines, subtle shadows and precise details (a horse’s sleek mane; a child’s hard gaze), Degas practices a nearly pathological form of perfectionism. Standing close and squinting at his careful strokes on Mlle Dembrowska, you start to get a feeling for who he was — an intimacy likely lost across the Louvre’s velvet ropes.

Speaking of the Petaluma Arts Center, Executive Director Richman concludes: “We feel like we’re this jewel that not enough people are aware of.”

If this exhibit’s fresh angle on a fascinating artist is any indication of things to come, she’s absolutely right.

Edgar Degas: The Private Impressionist runs through July 26, 2015 at the Petaluma Arts Center in Petaluma. For more information, visit petalumaartscenter.org.