In July 1861, 36,000 Confederate and Union soldiers faced off in the First Battle of Bull Run, the first major battle of the American Civil War. By the end of the bloody engagement, over 800 men were killed and thousands more were wounded. On the other side of the fractured nation, a more tempered — and seemingly separate — historical moment was developing. That same month, Carleton E. Watkins, a relatively unknown photographer, made his now-famous sojourn to photograph Yosemite Valley. The resulting images not only influenced the direction of art history, but also shaped the face of Yosemite and influenced the course of public policy.

Yosemite: A Storied Landscape, at the California Historical Society in San Francisco, pays homage to the natural beauty of the valley, which millions have admired for thousands of years. But the exhibition of painting, photography, ephemera, letters, and artifacts digs deeper, documenting the social history of Yosemite—how its mythology has been created, how its past has been distorted, and how it has shaped notions of wilderness and public land.

While in the valley, Watkins created 100 stereograms and 30 mammoth plate (22 by 18 inches) photographs. Copies of these photographs made their way to the east coast within a year, falling into the hands of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Oliver Wendell Holmes, among others. In December 1862, the mammoth prints were shown at Goupil Gallery in New York, immediately following an exhibition of photographs of corpses from the Battle of Antietam by Mathew Brady.

According to Dr. Anthea M. Hartig, Executive Director of the California Historical Society, it is believed that President Lincoln saw Watkins’ prints prior to signing the Yosemite Grant on June 30, 1864, which preserved the land under federal law and set precedent for the creation of the National Park System. It is difficult to imagine how Lincoln, who had never visited Yosemite, felt when he saw the solid granite Cathedral Rock puncturing the valley floor and reaching over 2,500 feet towards the sky. In such a moment, can a person locked in an existential battle for their nation feel a sense of tranquility or hope? Though we will never know Lincoln’s mindset, the five mammoth prints on display in Yosemite still possess the power to stun and humble, regardless of how many times one has visited the park or seen its infinite postcards.

The spectacle of over 150 years of representation of Yosemite was not lost on the exhibition’s curators. For many, even those who have visited Yosemite, access to the park is overwhelmingly through photographs, videos, and paintings. Visitors inevitably reach the park with a set of associations and assumptions already in place. Though often framed as natural and wild, Yosemite is a site of technology and media. Evidenced by its 3.8 million annual visitors, it is also a social place. Nowhere in the exhibit is this more poetically demonstrated than with photographers Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe’s Four Views from Four Times and One Shoreline, Lake Tenaya (2002). The panoramic view was meticulously stitched together with the artists’ own photographs and works from Eadweard Muybridge, Ansel Adams, and Edward Weston, who had each visited the lake over a seventy year period, shooting different locations and angles. Klett and Wolfe underscore that this glacial lake, high in the Sierras, is forever linked with the “outside” world, part of a web of social, artistic, and touristic meaning.

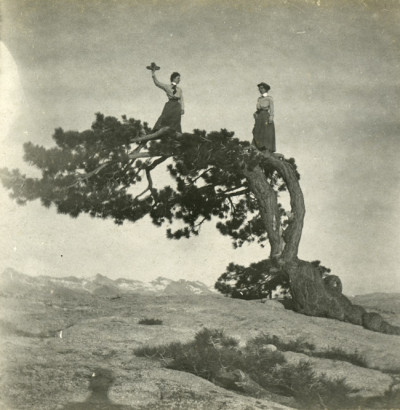

Another work by Klett and Wolfe recreates a 1940 Adams photograph of the famous Jeffrey pine atop Sentinel Dome. Shot at the same time of day, the shadows of the tree and nearby boulders fall on the exact same spot in both photographs. The mountains in the background look the same, of course, but less snow graces their peaks in 2002. The tree, however, has become barren, killed by drought, and a year later it fell to the ground. These photographs are paired with two others depicting the tree, a Watkins stereogram circa 1886 and an unattributed and undated photograph showing two women standing on the tree’s thick, horizontal branches. In Yosemite, even a tree can have 125 years of stardom.

Through stories about basket weaver Julia Parker, a Kashaya Pomo/Coast Miwok (Sonoma) artist who married into a Mono Lake Paiute (Sierra Nevada) family, the exhibition also relays the darker side of the the Yosemite creation narrative. Parker lived in Yosemite with her husband’s family until 1969, when the National Park Service destroyed their village to make room for campgrounds.

Parker’s baskets are accompanied by a photographic representation of a Smithsonian Institute diorama, ostensibly depicting a Yosemite Valley village, like the one Parker was displaced from. The diorama is accompanied with a story about a 1980s visit by Parker and Jay Johnson, of Yosemite’s Ahwahnechee tribe, to the Smithsonian, where they encountered the diorama with an explanation that there were no more Yosemite Indians left. Johnson and Parker confronted a museum staff person right then and Johnson insisted that he was in fact very real and very much alive. Though their presence is often erased or obscured, Yosemite highlights the work people like Parker and Johnson have done to preserve their own social history.

Yosemite: A Storied Landscape ponders whether the creation of the park was meant to offer the embattled nation a place to heal during the Civil War. Yosemite has undoubtedly functioned as a refuge and a site of catharsis for many. But just as Yosemite isn’t a completely wild place, it hasn’t always been a place of serenity. The valley has also represented conflict and turmoil, from violent geological activity to the 1850–51 Mariposa War between gold miners and the Ahwahnechee to modern conflicts over Hetch Hetchy and the expansion of federal land. This varied history makes the photographs of Klett and Wolfe particularly germane — two people can look at the same valley, at the same hour, in the same season and see two very different scenes.

Yosemite: A Storied Landscape runs through January 25, 2015 at the California Historical Society in San Francisco. For more information visit calhist.org.