Editor’s Note: Bay Area Painting Right Now peers into the studios of emerging local painters to find out what they’re making, how they’re making it and why. Guiding our tour is Brandon Brown, poet, writer, editor and unabashed fan of contemporary painting. Don’t miss the first installment of this series on Lana Williams.

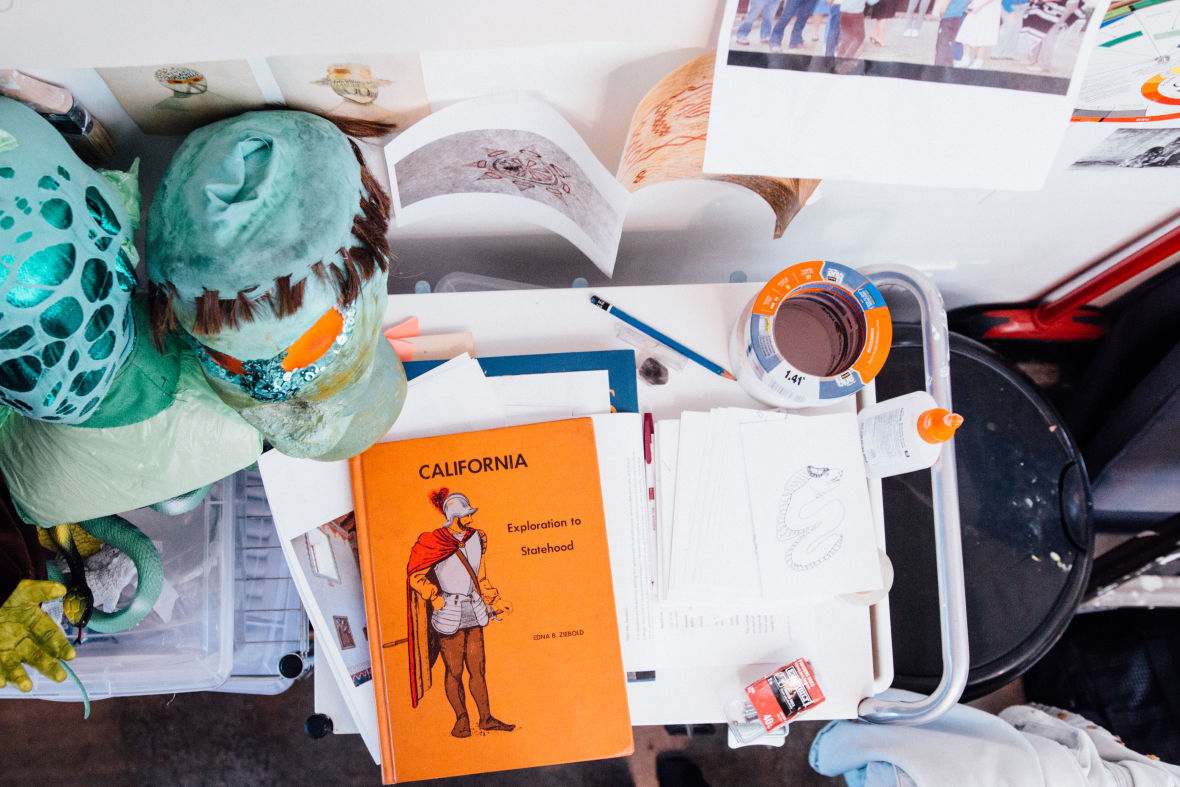

Katie Dorame paints in an ample structure in the yard behind her northwest Oakland home. Paintings and drawings line the right wall of the studio, while the left wall is covered by an eclectic bunch of materials: paint and supplies, frocked space aliens and tacked-up papers, including a still from Pee Wee’s Big Adventure.

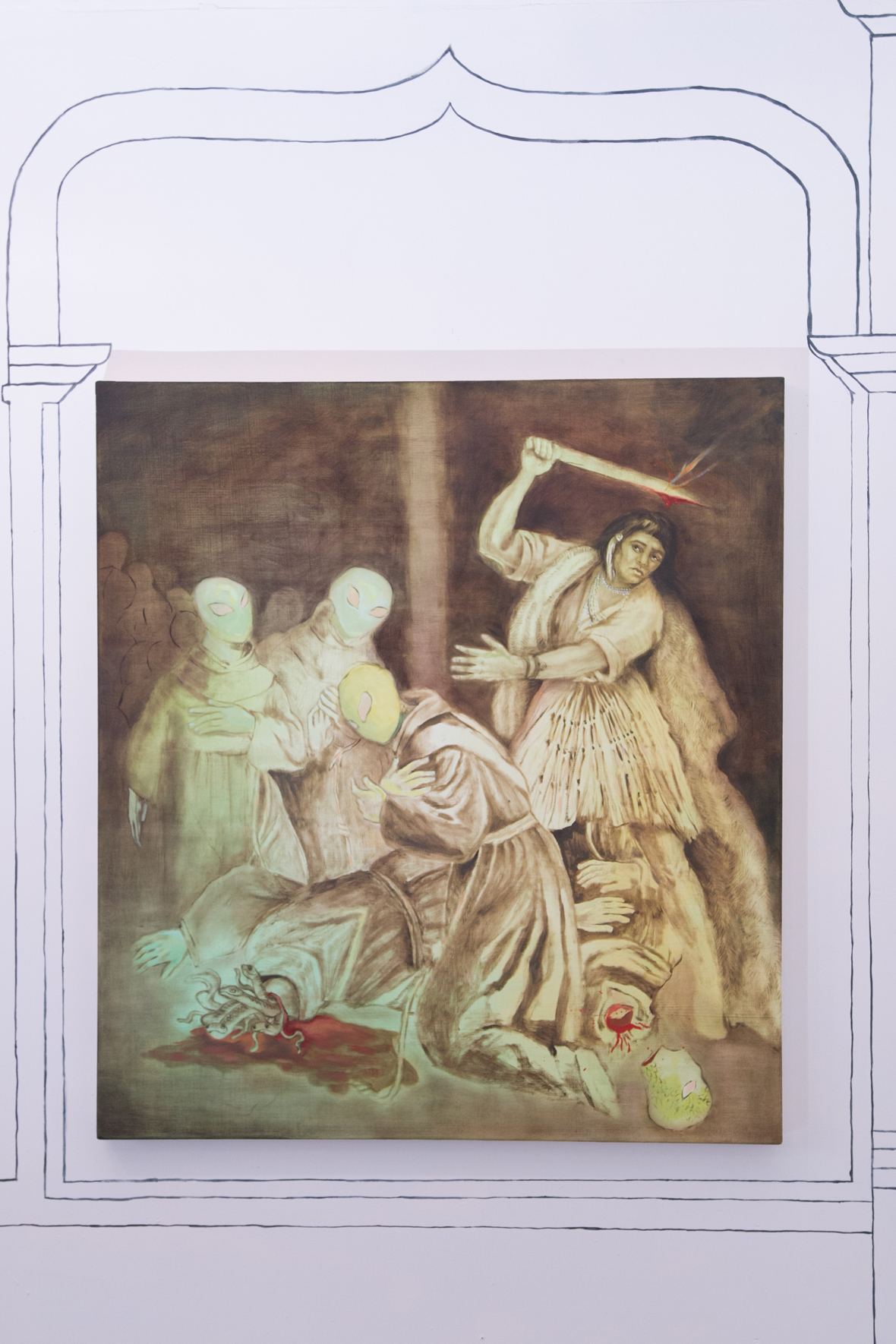

At the rear of the space, the atmosphere changes dramatically. It becomes less of a studio and more of a set. Two large oil paintings flank the back wall, suggesting the religious paintings one finds in Catholic churches. And indeed, designs painted on the wall around the canvases refer to a particular form of architecture — the California mission.

The Spanish built 21 missions in California between 1769 and 1833. They were religious and military outposts, administrative centers through which Spain waged a colonial effort to subjugate the indigenous people of California. Visiting them now is a strange and complex endeavor.

On one hand, the buildings are among the oldest surviving religious structures in California, inspiring writers like San Francisco’s Bruce Boone in his legendary My Walk With Bob and Alfred Hitchcock, who used Mission San Juan Batista in his film Vertigo. On the other hand, the missions are remnants of a centuries-long war against Native Americans. Every element of these buildings, from their foundations to decorative ornaments, is a relic of extreme violence.

Dorame’s interest in the missions is tied to the critical focus of her painting practice: narrative. As we discussed her growing interest in art as a teen, she described the moment she realized painting was a way for her to tell stories. In this way, Dorame’s extraordinary interpretations of the missions, California history and the artwork they’ve both appropriated and inspired, enter a long tradition of other interpretations about what the missions represent.

This is not simply a detached historical affair for Dorame however — she herself is Tongva, and the Tongva people are occasionally called “Gabrielenos,” referring to the closest Spanish mission in the San Gabriel Valley.

Dorame’s current works, many of which will appear in the group exhibition Indigenous Contemporary at the University of San Francisco (another Catholic institution with a complex history), opening in November, use existing historical artworks as points of departure.

I think of Dorame’s works as translations; she revises existing imagery into her own idioms. Take Mission Revolt for instance, derived from an extant painting in one of the California missions. In the original, a “Turk” is shown beheading an innocent angelic friar. In Dorame’s version, it is a proud indigenous warrior who swings the machete. Snakes crawl out of the neck of another headless friar, underscoring the painting’s reversal of the way colonial priests are usually pictured.

Ink drawings, watercolors and oil paintings line the walls of Dorame’s studio. The watercolors, which show portraits of Native Californians drawn from the popular anthropology texts Dorame collects, have an unusual depth and richness. On the other hand, the oil paintings, which typically embody the pondering gravitas of the medium’s history, are painted with an extremely deft and light touch.

In Neophyte Baptism, the under-painting is evident in many sections of the canvas. Where there is detail, it is significant, as in the pointed nails of the friar conducting the ceremony — so sharp and gaunt, they appear menacing, claw-like.

And what about Dorame’s interpretation of the friars themselves? Represented in the poses and costumes of Mission-style paintings, Dorame’s holy men boast the reptilian heads of extraterrestrial invaders.

Their radically altered faces are funny, obviously. But as Dorame pointed out, they also offer an alternative interpretation of colonial violence. Reflecting on the insane brutality of Spanish conquest, Dorame’s work questions the humanity of those who perpetrated and facilitated this brutality. Further complicating her depictions, the Spanish friars are not the only ones implicated in this transformation — she shows their indigenous converts as undergoing reptilian morphogenesis.

Dorame’s use of the scaly alien face joins other appropriations of cinematic imagery in her practice. While growing up in Los Angeles, one of Dorame’s entries into artmaking was drawing old film stars. “My mother loved movies, as long as they had a happy ending,” she says. Dorame’s Sifting Screens, a 2013 solo show at Galería de la Raza, focused on actors of color in Hollywood’s golden and silver ages.

Film remains a strong concern in her paintings. In Pee Wee’s Big Adventure, she noticed the scenes supposedly set at the Alamo were actually filmed at Mission San Fernando. Above the Alamo’s “gift shop” sign, an ornate design identifies the building as the mission’s exterior.

This design is a Fernandeño Tataviam image, created by a Native American community that retained their traditional languages and many aspects of their social, ceremonial and political life even during the mission era.

For Dorame, this unintentional reference connects indigenous California art, the missions, Hollywood films and the “sifting screens” through which history reveals itself in architecture, film and painting.

It’s often remarked that history is told from the vantage of the victors. In that respect — or rather against that respect — Katie Dorame’s paintings recode the structural and ornamental signs of conquest, as embodied by the architecture, interiors and historical narratives of the California missions. Using the sights and shapes of a complex, violent and still resonant tradition, her paintings stage a refusal of that tradition that is stubbornly contemporary.