At San Francisco’s Goethe Institut, Homestory Deutschland presents photographs of Afro-German men and women alongside their achievements in various areas of society. Much more than documents of history and identity, these photos and bios form narratives of the journeys many Afro-Germans undergo as they search for a sense of belonging.

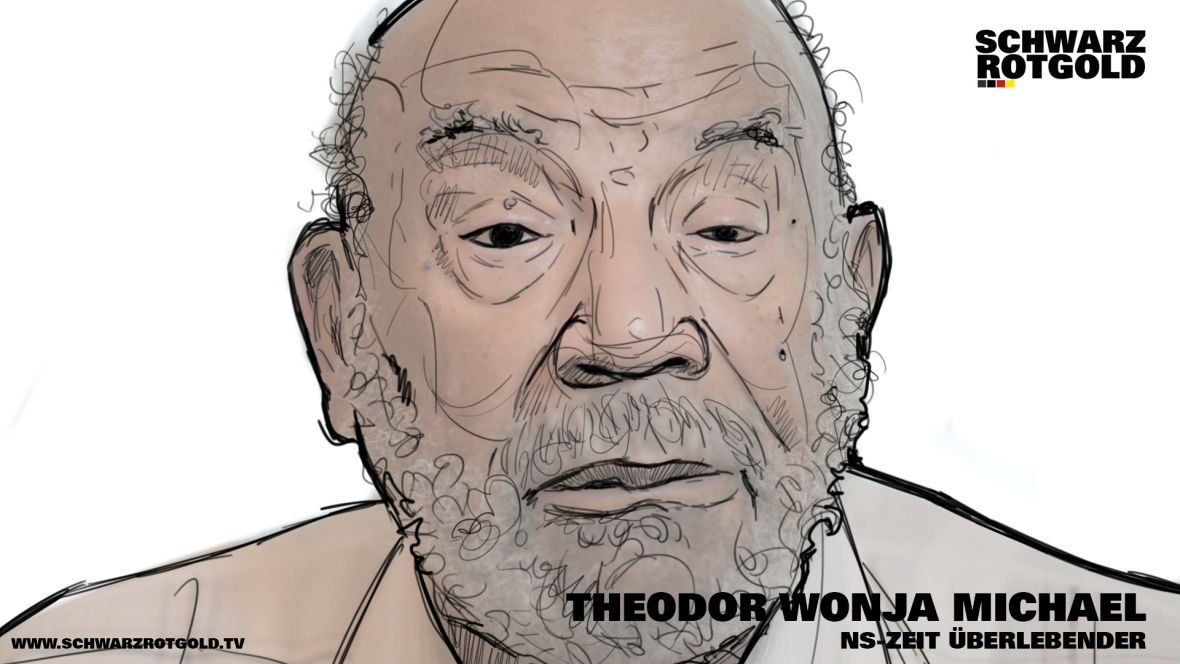

The exhibition also includes a video series called Schwarz Rot Gold, tackling the topic of identity through a web series in which host Jermain Raffington interviews fellow Afro-Germans on race and life in Germany.

For Victoria Toney-Robinson, Homestory Deutschland is personal. She was active in Hamburg with the Initiative of Black People in Germany (ISD) and contributed writing to a profile featured in the show. Toney-Robinson moved to Oakland from Hamburg four years ago in search of an activist community and a sense of home.

This is her debut as program curator for the Goethe Institut. The event series features films and discussions based on Black German or Afro-German narratives. Toney-Robinson has already seen an increasingly racially diverse crowd attending the events.

As she took me around the exhibit to show me the different names and histories of the individuals featured, she paused at May Ayim’s picture. Ayim was a poet, activist and one of the founders of ISD; she took her own life in 1996. Toney-Robinson pointed to a photo of writer and lecturer Olumide Popoola on the next wall, whose brother also killed himself.

Toney-Robinson moved to Oakland in an attempt recover and recharge. “If even the strongest of us that are loved by so many in the community break, or are broken by these struggles, for me I had to step out,” she says. “You are always told in so many subtle and not so subtle ways that you don’t belong.”

The same struggle with identity and belonging inspired the web series Schwarz Rot Gold. In it, Jermain Raffington interviews ten Afro-Germans across the country discussing the past, present and future of racism in Germany.

Growing up in a small village in southern Germany, Raffington was the only black kid in his class, and the tallest. Catching up with Raffington at a café in Berlin he told me stories of his childhood, including those of strangers touching his hair while he stood at a stoplight with his mother (who is a white German).

“My mom was very open and loud about it,” he says. He was constantly questioned, “where are you from?” and struggled to find an answer. To further complicate matters, when he went to the U.S. on a basketball scholarship to attend Butler University he was seen as a German, which was for him, “even weirder.”

Raffington found many of his interviewees had similar experiences. “There was always a point of time where externally someone said you are different,” he says.

Despite Germany’s past, Raffington is hopeful for a future in which people are aware and working to fight biases without putting everyone who looks a certain way in the same category. “I think that is the first step of shaping a new society,” he says. “Because otherwise you are running on a cycle of past craziness.”

Theodor Wonja Michael, an actor and journalist who survived the Nazi regime, is featured in a still photograph, but comes to life on-screen in his own chapter of Schwarz Rot Gold. In the trailer for the series he says, “I look black. But what is underneath this skin?”

This sentiment echoes Toney-Robinson’s aims with Homestory Deutschland. It’s about “telling stories, sharing stories and listening to each others stories,” says Toney-Robinson. For her and Raffington, these projects assert identity by witnessing shared struggles.