As odd as it may sound, there’s never been an art exhibition dedicated solely to the visual beauty of Lake Tahoe. Enter the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno, which has dedicated its entire 15,337 square feet of gallery space to this purpose.

The result is Tahoe: A Visual History, a collection of photography, sculpture, paintings, early survey maps, Native American basketry and architecture.

The story begins with the first paintings of the area in the latter half of the 19th century. The exhibition features examples from the golden age of landscape painting. Hudson River School hyperrealism meets the added punch of spiritual transcendence; it was a time when belief in nature’s divine origins held sway.

Paintings by notables such as William Marple, Thomas Hill, Albert Bierstadt, William Keith and John Ross Key portray wide-open vistas around the lake. But for me, the images that really impress are those of a more intimate nature. Bierstadt’s Emerald Bay, Lake Tahoe (1871) is an underwater scene — a highly unusual subject for the artist — depicting the glorious clarity of the lake’s water in an unexpected close up.

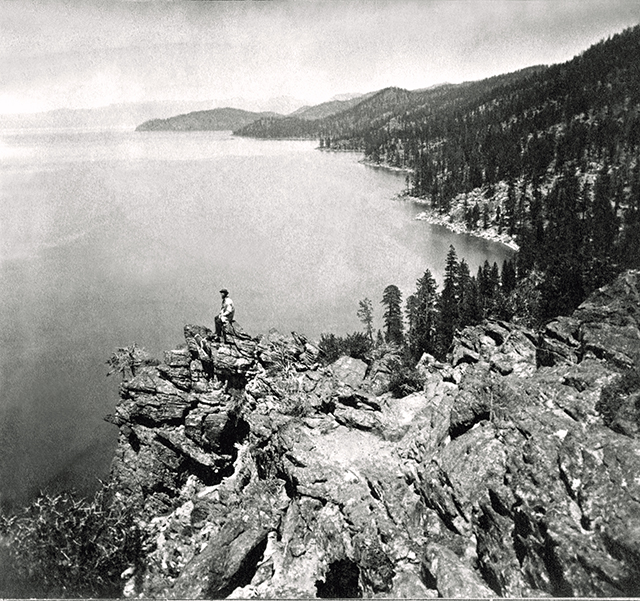

Photographs from the 1860s and ’70s document the building of the Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR) and bring the impressive engineering feat to life. Originally planned as a way to record the railroad’s progress while luring additional investment money, the images serve up a heavy dose of Manifest Destiny. These photographs of progress also helped to dispel connections between the Sierras and nightmarish memories of the Donner Party.

The railroad baron Collis P. Huntington commissioned a specific piece from Bierstadt to celebrate the completion of the trans-Sierra portion of the railroad, a painting of Donner Lake as seen from Donner Summit. The huge, 6-by-10-foot canvas more or less ignores the train (probably to Huntington’s consternation), but the painting was hailed as a masterpiece at its 1873 unveiling at the San Francisco Art Association.

Flash forward to the present day, where the museum itself commissioned artist and architect Maya Lin to create a suite of three sculptures for Tahoe: A Visual History; the resulting artworks help visitors visualize complex natural features. Secchi Point (2014) is a series of cut glass globes that represent annual rainfall totals in the Tahoe basin over the past 50 years. The large-scale wall installation Pin River – Tahoe Watershed (2014) outlines the shape of Lake Tahoe and its intricate system of tributaries with straight pins. And Cloudline: Mt Rose at 8,500 ft (2014) recreates the mountain’s dramatic peak as a marble topographical model.

Also on display are wonderful examples of basketry by the Washoe, the native people of the Lake Tahoe region. In the early 20th century, hand-made decorative items like these were in high demand. Promoters gave lectures on Native American culture, clubs devoted themselves to collecting basketry, images of baskets filled books and magazines. The examples shown at the Nevada Museum of Art range in size from that of a thimble to very large burden baskets in the largest exhibit of Washoe basketry ever assembled.

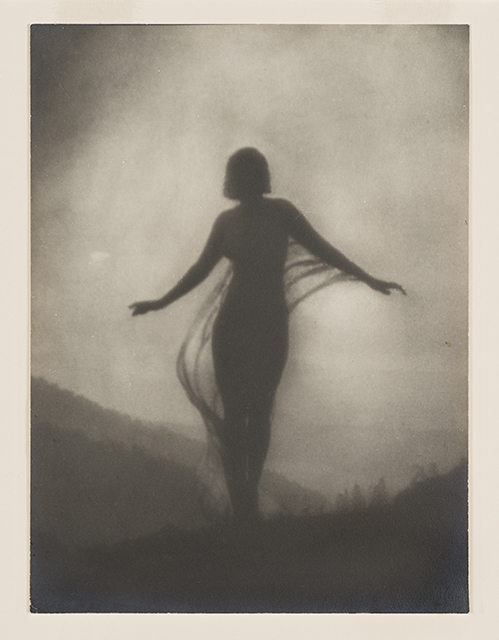

My favorite part of the exhibition though, is the photography of Anne Brigman. She was an independent spirit (to put it mildly). Starting in 1904 she took her camera, a few essentials and headed into the mountains for weeks at a time — sometimes alone, sometimes with friends. Her imagery is ethereal: a nude figure against a backdrop of mountain scenery. Her methods were radical for the time period, but her gelatin silver print photographs capture human subjects in complete harmony with their landscapes. They are simply extraordinary.

Tahoe: A Visual History is on view through Jan. 10, 2016. Visit nevadaart.org for more information.