Andrea Fraser isn’t afraid to make you uncomfortable. As an artist whose practice includes institutional critique, she’s known for pointing out unconscious biases and capitalist motivations in art museums.

Her more notorious works over the past decade merge art-world commentary with issues of gender: in Official Welcome (2003), she made a speech parodying art-world personalities while matter-of-factly removing her clothes; in Untitled (2003), the artwork required the purchasing collector make a sex tape with her, which then became the work itself. Using her body as her primary medium, Fraser’s performances dive deep into complex topics.

Men on the Line: Men Committed to Feminism, KPFK 1972 (2012), produced by the Wattis Institute in collaboration with the Pacifica Radio Archives, performed at San Francisco’s Brava Theater on Oct. 30, likewise follows suit, but it’s a comparatively tame piece — Fraser remains fully clothed. In this one-woman show, she recreates a public radio broadcast of four men discussing their relationship to feminism in 1972, during the height of the second-wave feminist movement.

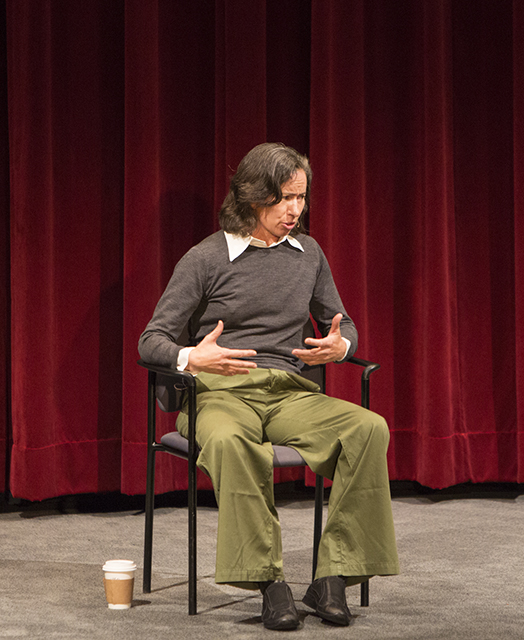

In a packed house on Friday, the performance started abruptly when Fraser entered the stage. She wore fairly “masculine” or unisex clothing, and the stage was empty except for a chair. The original radio production’s introduction played, beginning with John Lennon’s “Working Class Hero.” Then, a clip of feminist artists Judy Chicago and Isabel Welsh discussing internalized stereotypes and gender role power dynamics played. In 2015, Fraser sat listening, nodding thoughtfully.

When the clip ended, Fraser sprang into character as self-proclaimed “host/participant” Everett Frost, who introduced the three other men in attendance: Bob Krueger, Lee Christie and Jeremy Shapiro. To represent each man, Fraser altered her speech and body language. Depending on who was speaking, she leaned to the side or sat upright, feet firmly planted on the ground or legs crossed in a wide, manspreading kind of way.

The initial shifts from each character were amusingly drastic, facilitated by how entirely Fraser embodied the roles. Her facial expressions seamlessly mirrored the voices: a little smug, then self-conscious and uncertain, complete with sighs, chuckles and uncomfortable pauses.

The men discussed the difficulties, both emotionally and socially, of being male feminists. Even as the “glorious sense of equality” was celebrated, one man was honest enough to admit he missed the past when “I was… king and I had a slave… I feel that’s the wrong way to be, but [with equal gender roles], you’re confronted with all sorts of new problems.”

The topics left unsaid in 1972 are telling. Racial difference was only explicitly mentioned once, when a man compared relating to women with the difficulty of fully relating to the “black revolution.” Briefly and self-consciously, the men mentioned the accusation of being “queer.” The participants clearly portrayed themselves as straight, white men.

To deepen the conversation, Christie, a psychologist, offered a meditative exercise. He described an “inverted” reality in which women were the dominant social group holding power in legislation, media and family. Although distraught by this prospect, the men settled on the reassuring conclusion that feminists don’t want women to dominate society, but desire genuine equality between the sexes.

Nearing conclusion, the men noted that the feminist movement fostered their ability to express emotions to other men. Here, Fraser’s eyes welled up with tears, grimacing as she slowly forced out words. She wrapped her arms around herself in a long embrace, mumbling mostly unintelligible but sympathetic comments. “Working Class Hero” began to play. Fraser stood and walked offstage.

After the performance, someone suggested to me that Fraser had altered the original transcript. Curious, I obtained a copy of both Fraser’s script and the original KPFK recording. The changes are minimal, and Fraser’s version clearly notes the piece has been transcribed and edited by her.

In the midst of comparing, I questioned my own motives. Focusing on the technical how of a specifically feminist art piece is arguably easier than the why.

It’s tempting to think Fraser mocks the men, ensconced in privilege while they claim to be (and I quote) “cured of sexism.” But there is also sincerity and genuine emotion in the men’s desire for social change.

She doesn’t direct the audience to form any specific conclusions, but asks for a comparative evaluation. What relationship do men have to feminism today? And from there: what relationship to feminism do women have today? Given that it’s not entirely common for men or women to identify as feminists in 2015, what is feminism now?

Influenced by the intersectional emphasis of today’s third-wave feminism, one might answer: attention to more than two gender identifications, and certainly more than one dominant racial and ethnic group, class, sexuality or ability. But it’s not clear from Fraser’s work where she’d like audiences to land. This lack of a conclusion, aided by the abruptness with which she entered and exited, puts the onus on individuals to do some careful thinking.

Considering Fraser’s history of performance topics, it’s still noteworthy that Men on the Line doesn’t discuss the art world as such. True, Shapiro taught at CalArts, Frost was married to feminist artist Faith Wilding, and yes, citing Judy Chicago is a direct reference to the arts. But the work itself doesn’t emphasize those facts.

Fraser’s decision to focus on gender as a general social issue is, perhaps, an attempt to get at the roots of the subject. Without systemic change in society at large, seeking equality in the art world is futile. Both like and unlike the men Fraser plays, she’s aware that the personal is political; it’s the public as a whole that needs restructuring.