Bay Area artist Amy Balkin doesn’t make paintings or sculptures, and she doesn’t have a photographic practice. In fact, you can’t see her artwork PUBLIC SMOG at all. But that doesn’t mean it’s not there.

PUBLIC SMOG is a public park in the sky, created by buying carbon offsets. At a time when the air we breathe can be bought and sold on the free market, Balkin’s mind-bending conceptual art project seeks to protect that atmosphere by any means necessary — even if that means taking her case to the highest court in the land: the United Nations.

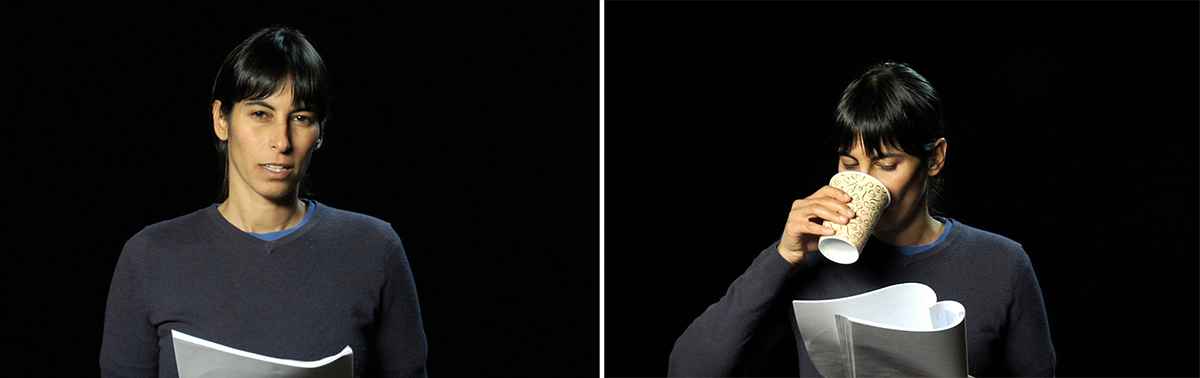

Listen to a discussion about PUBLIC SMOG between artist Amy Balkin and KQED’s Sarah Hotchkiss:

The ongoing artwork, currently on view in the form of the project’s paper trail and an accompanying slide show in the Mills College Art Museum’s exhibition Public Works: Artists’ Interventions 1970s – Now, began when Balkin started looking into carbon offsets, a trading scheme by which organizations or individuals can purchase credits to counter the negative environmental effects of their activities. Some carbon offsets fund renewable energy sources; others sponsor forestation projects. Regardless of their motives, all come under fire from some environmental groups as a quick method of alleviating carbon guilt without actually curtailing the sources of pollution.

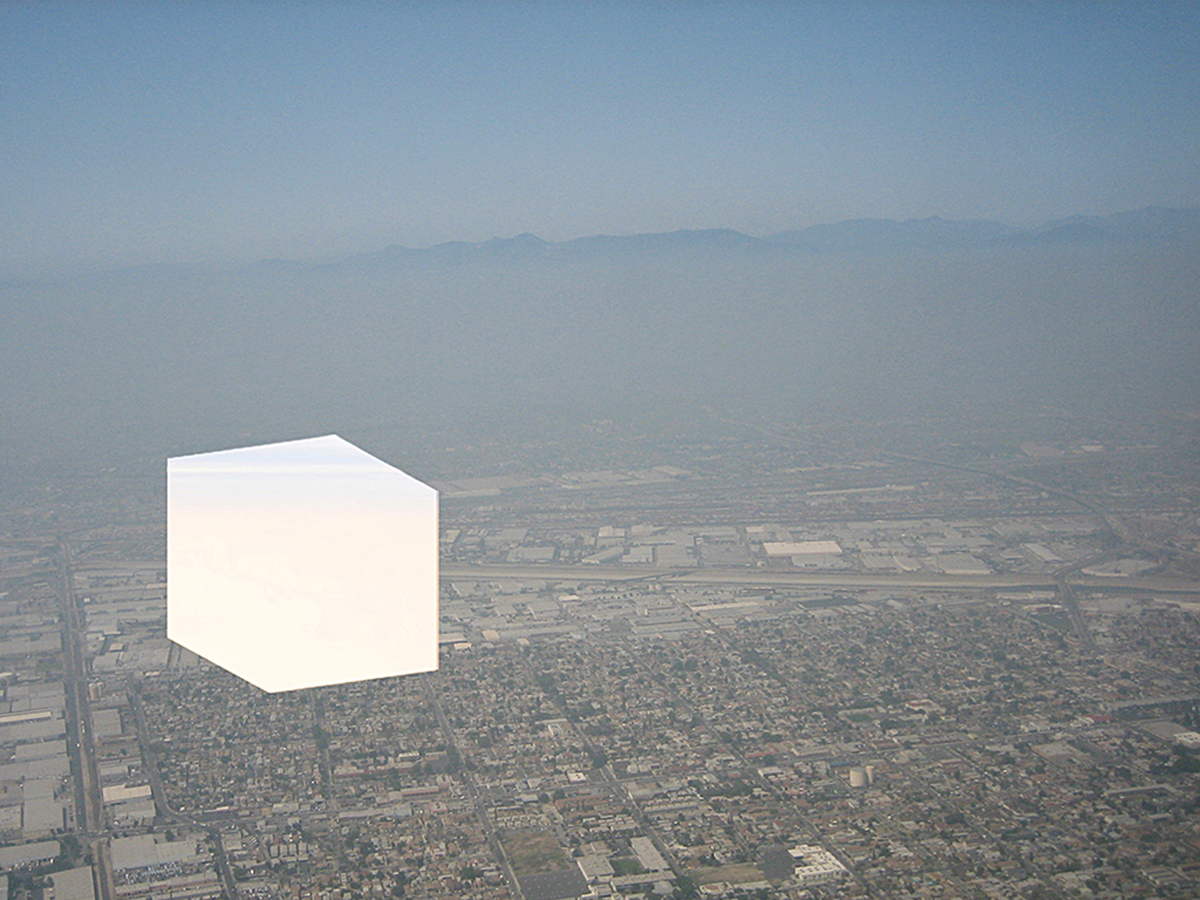

In 2004, Balkin first entered the emissions trading market and purchased the right to emit nitrogen oxide — a greenhouse gas — in Southern California. Instead of using those rights, she withheld them, making the offsets inaccessible to polluting industries and reserving that portion of the atmosphere as a “clean air park for the public.” Depending on the type of greenhouse gases the artist buys the rights to emit, the park manifests in different parts of the atmosphere. “The park isn’t something you can see,” Balkin says. “But it is something you can use.”

But how exactly do you use a park you can’t physically access? Depending on which greenhouse gases Balkin buys the rights to emit, the park manifests in different parts of the atmosphere. Nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide and ozone all contribute to smog in the troposphere — or in the language of PUBLIC SMOG, the “Lower Park.” Carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide are the greenhouse gases of the stratosphere — aka the “Upper Park.”

Balkin lists the benefits of opening each park (that is, buying certain offsets) with a playful upswing in her voice. “The Lower Park features particulate-free breathing and lower risk athletic activity,” she says. “And the Upper Park activities include the ongoing enjoyment of glaciers, birds, plants, islands and coastal areas.”

Even if you personally can’t get to a glacier during a park’s open hours, know that someone, somewhere — maybe a polar bear — is enjoying its continued existence.

Balkin has long been interested in what happens when land, water and air become commodities — and how people become dispossessed from their own environments. A People’s Archive of Sinking and Melting, one of the artist’s ongoing projects, gathers items from places around the world that may disappear due to the effects of climate change. In the collection, the abstract facts and figures of rising sea levels, coastal erosion and desertification become personal stories illustrated by hand-picked mementos. This is the Public Domain, also ongoing, attempts to create a permanent international commons, free to all forever, on 2.64 acres of land near Mojave, CA. And Invisible-5, an audio tour of Interstate 5 from 2006, tells the stories of communities along the highly polluted corridor and their struggle for environmental justice.

Acknowledging the satirical aspects of PUBLIC SMOG, Balkin is also quick to point out the serious environmental implications of the project. “It opens up a way for rethinking atmosphere, and a way for helping to remember the atmosphere. We’re breathing it, but we might not be visualizing it, or thinking about what that pollution looks like or its impacts.”

Balkin last opened a clean air park for five months in 2010. Since then, the project has morphed into a different kind of campaign: a political one. The artist is now hard at work trying to get Earth’s atmosphere inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List.

UNESCO deems sites on the list to have “outstanding universal value” and each site must meet at least one of 10 superlative-heavy criteria. Today, the World Heritage List includes 1,031 properties, ranging from historic Cairo to the Bikini Atoll Nuclear Test Site to California’s Redwood parks.

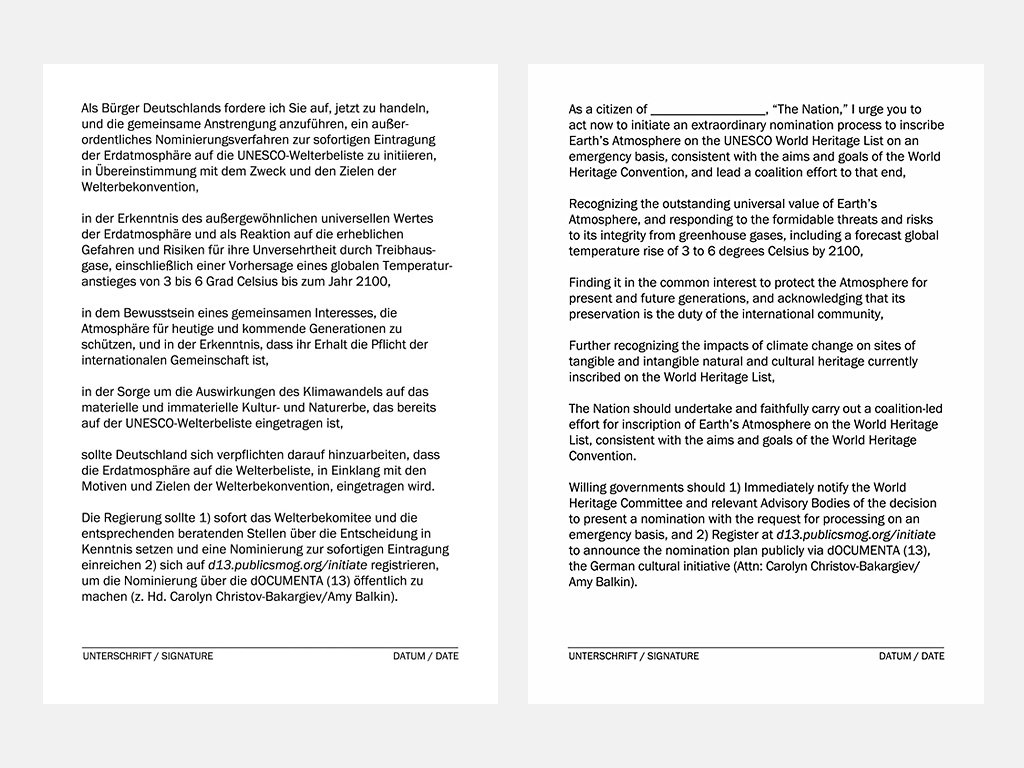

Balkin’s bid to get the atmosphere on the list gained momentum with her participation in documenta, a high-profile international art exhibition in Kassel, Germany that takes place every five years. When Germany said no to backing Balkin’s bid to UNESCO, her installation at dOCUMENTA(13) spawned a postcard-writing campaign, with 100,000 visitors from around the world sending letters to their governments in support of the atmosphere’s place on the World Heritage List.

While any country able to back the bid has yet to volunteer — the only positive response came from the Kingdom of Tonga, an archipelago in the South Pacific dealing with rising sea levels — Balkin points out that all properties currently inscribed on the World Heritage List, whether they’re tangible or intangible, will succumb to the effects of climate change if atmospheric pollution isn’t addressed. “There’s a fundamental reflexive opportunity there,” Balkin says.

Tanya Zimbardo, co-curator with Christian L. Frock of the Mills College Public Works exhibition, says they wanted to include PUBLIC SMOG because it’s both invisible and ubiquitous, impossible to ignore. “Some works in the show are focused on more traditional ideas of public space, plazas or street corners,” Zimbardo says. “This is something that is much more. This is thinking about a larger sense of borders or lack of borders, something that is different at different moments.”

“One of art’s capacities is to expand possibility. It’s to help think through problems of living,” Balkin says. The United Nations conference on climate change begins next week in Paris. And while the world’s leaders will float various schemes, goals and proposals in an attempt to slow the devastating effects of climate change, in the meantime we have PUBLIC SMOG, another model for what might be.

Public Works: Artists’ Interventions 1970s – Now is on view at the Mills College Art Museum in Oakland through Dec. 13, 2015. Visit mcam.mills.edu for more information.