One of the things I’ve learned from writing this series is that it’s always better to see a painter’s work in their studio. Yes, the gallery and the museum have their little auras and theatricality, but the studio is the architectural organization of how paintings come to be.

I met Mahader Tesfai at the studio he shares with two other artists in uptown Oakland. Stevie Wonder’s Songs in the Key of Life spun on the turntable as we talked and looked at his works: I don’t want to bore you with it / Oh but I love you, I love you, I love you.

In Tesfai’s space, his works are to be seen, touched, held, moved and rearranged. His practice adapts to the medium and the surface: glow-in-the-dark paint on white canvas shoes, 3D glasses and a Stevie Wonder soundtrack.

Mahader Tesfai was born in Eritrea and raised in the Bay Area. He earned a B.A. in Black Studies from UC Santa Barbara. Eritrea, Oakland, Santa Barbara; these are the places he’s from, and each resonates in his paintings. The stylization with which he renders his faces hearkens back to East African figurative works. Oakland is everywhere, from the surrealist couture of his painted t-shirts to the tradition of radical politics his paintings thematize. Finally, his studies in Santa Barbara, a place demographically far different from Oakland, permeate the theoretical underpinnings of these paintings.

Tesfai only started painting after college, where his studies in Black theory and history influenced his developing interest in visual art. He centers Black bodies and lives in his paintings. With a nuanced understanding of how those bodies and lives have appeared in a racist Western painting tradition, his work stages a formal refusal to participate in and reiterate that bad legacy.

Just as these places, the places from which Tesfai hails and regards in his work, offer wildly different social ecologies, imagery and sensory information, the styles he accommodates in his work are also extremely varied. Thematically, however, they are made coherent by the centrality of Black faces.

Tesfai recently told an interviewer, “The figures in my paintings and illustrations are depictions of Africans. My art work ranges from figurative to abstract but the African is always present.”

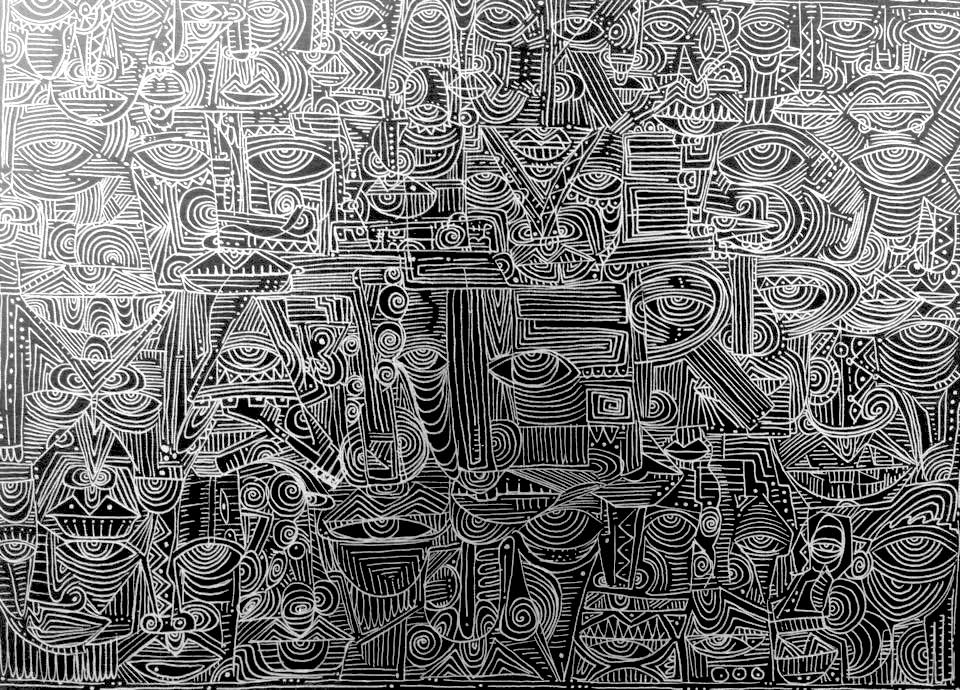

The “range” he describes is unmissable. Some works use sparse brush strokes to evoke the figures of overlapping faces. Others rely on intricate thin lines to give the feeling of a gathering crowd, that crowd clustering into shapes that signify letters and words.

Looking at Untitled, a painting on top of a large paper poster found at the Marcus Garvey Bookstore, we passed around 3D glasses. Seen through the red and blue plastic lenses, the lines have a kinetic quality that makes the pastel tones pop off the poster’s shrink wrap. This viewing experience underscores the importance of standing in front of Tesfai’s work, of looking into the faces that look back.

His paintings are richly textured. In fact, many of them are more properly classified as collage with painted elements. They also change in their significations depending on your proximity to the surface. Looking at Untitled up close, for instance, Tesfai’s pastel colors and slender lines repeat almost identical faces. Stepping back, however, one sees how the faces themselves spell out a text, a message.

Faces glean information from stimuli, and are also of course objects read by others for meaning. In Tesfai’s work, the faces are literally transformed into words, into a message. The message is about life, the key of life in the Wonderian sense. The overlapping of the faces is a crucial relation in Tesfai’s paintings. He suggested to me their relationship to iconographic religious painting in an African style.

These paintings, for me, invoke solidarity, from the literal embedding of slogans like “Black Lives Matter,” to Tesfai’s use of iconic 20th century Black leaders in his composition. Solidarity beckons you to come close, and to look into the eyes of the people you gather with.

Solidarity also demands distance, contemplation and study. These paintings address themselves to the struggles (against capitalism, against white supremacy and systemic racism, against the violent urban armies called cops — not that these things can be separated) without fear or compromise. And in this regard, I think of the thickly accumulated bodies. These carriers of messages overlap with others until there can be no perfect distinguishing of one from another. Bodies in a crowd come together to offer the police nothing and the people everything.

When you look at Mahader Tesfai’s paintings, you see faces — faces in different styles and from different places. Two faces overlap each other to become one face with three eyes. Huge crowds of bodies make a great multitude of gestures more alike than different. They are Black faces. They are African faces. The faces are the story and the faces tell the story.