A couple years ago, Timothy Buckwalter began to proclaim — loudly — on Facebook that he had landed his “dream job.” Then, in the weeks following this announcement, he shared — often, and to an annoying degree for those of us in the coalmines — how happy he was in it. This habit has persisted to the present day. The dream job in question is Gallery Director and Director of Marketing at NIAD (National Institute of Art & Disabilities) Art Center in Richmond. So, I suppose he can be excused when the surplus joy he feels working with a group of talented and productive artists spills into his Facebook status. Buckwalter is the kind of guy who has always fed off of and then feeds back into creative communities.

I have known Tim for decades, and seen him operate in various capacities within the Bay Area art world. I am a fan of his art (he is a painter, collage and archive artist), and of his work promoting other artists. For a much-too-brief period about five years back he also contributed to KQED Arts. Last spring, Buckwalter asked me and my partner, ceramic artist James Aarons, to curate a show, I Have Always Been a Storm, of recent work by NIAD artists, which opens this Saturday.

Having visited him at NIAD, I can easily understand why managing the art center’s exhibition and publicity programs would be Buckwalter’s dream job. There is an incredibly active studio and what appears to be a surplus of formal and conceptual genius there. It’s also a bit of a scam if you ask me; I never visit without being fleeced. I think they pump something into the air that fills me with want at the sight of so many great pieces of art. I know I have a problem and should probably learn to forget my wallet before going.

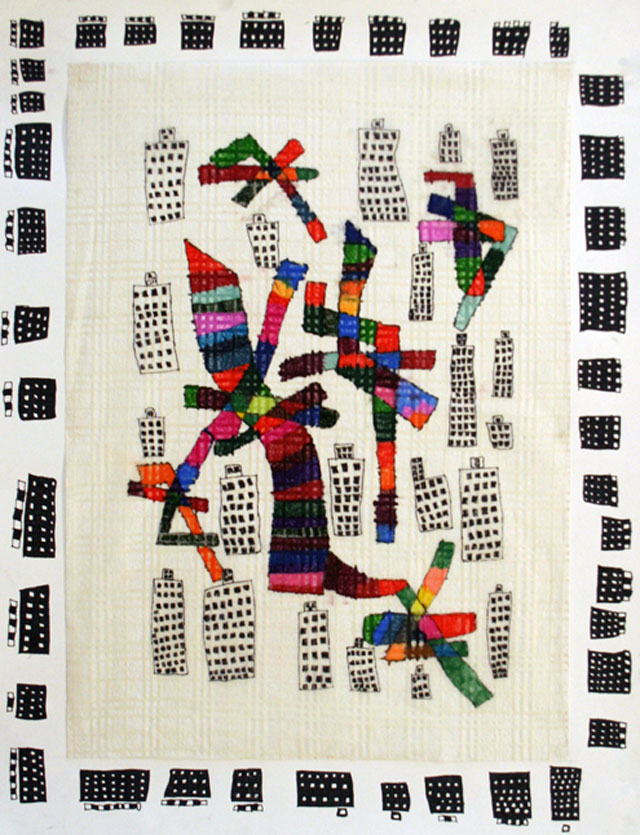

NIAD was founded in 1982 to “promote meaningful independent living by artists with disabilities.” Aided by top-notch instructors and studio helpers, artists work in various media (painting, ceramics, printmaking, sculpture, collage, textiles, etc.) in a large, active, open studio, which occupies about half of its Richmond location. The other half is storage space, a kitchen, a large gallery and a storefront. There is also a courtyard populated with umbrella-shaded lunch tables and large ceramic sculptures.

Buckwalter has been a contemporary artist since 1988, when he graduated from the Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia. He moved to the Bay Area in 1992 and began engaging with the art scene here, showing in various galleries around the Bay. In 2006, he lost the lease on the Berkeley warehouse where his studio was located and started working at home, where he developed a serious case of “artist’s block.” He started writing about art (for KQED, East Bay Monthly, SF Chronicle, etc.) and first came into contact with NIAD when then-gallery director Brian Stechschulte encouraged him to come to Richmond after reading a profile Buckwalter had written about Creative Growth, a similar kind of space operating out of Oakland. He later included some of the people he encountered at NIAD in a group show of Bay Area artists he curated for a Los Angeles gallery, which ended up selling some of the work. When NIAD asked him to organize a show from the archive for its 25th anniversary, Buckwalter invited a group of artists and arts professionals (including me) to organize the show. The success of that exhibition led to more opportunities and the partnership kept growing.

Buckwalter was unemployed and helping his wife, Nell Bernstein, research her book, Burning Down the House: The End of Juvenile Prison, when he got an email from Stechschulte saying he was leaving his position at NIAD and asking if he could think of anyone who might want the job. He could.

When I ask what, beside the obvious, makes this his dream job, Buckwalter responds, “I’ve got to be honest. I never had any interest in the art world outside of creating art. Eight years ago, that changed. I then had an interest in writing about art. Now, it’s changed again where I have an interest in selling art.”

“I actually love organizing stuff. I’m a collector. I collect art. I collect records. So having the opportunity to organize stuff is super-exciting to me. Every two months — in 2015 we are going to do it every month — I get to organize a show.” But Buckwalter quickly realized that, in order to have an exhibition program that truly represented what was going on in the studio, he would need to invite other people in to curate. He says, “I have specific artists I like or whose work I relate to. I look at it and there’s a connection, or I have a connection with that person and maybe I’m not crazy about their work, but I think they’re great and I want to sell their work. Inviting other people in helps me look at the work differently. It helps me get out of my head and see NIAD anew.”

But, from the perspective of a guest curator who is also an artist, the experience can be a little intimidating. Some artists struggle to free themselves more than others. Every time I go to NIAD I am faced with my inhibitions, my inability to let go of insecurities or certain ideas or ambitions for my work, which prevent me from creating or stop me from following the work where it is trying to lead me.

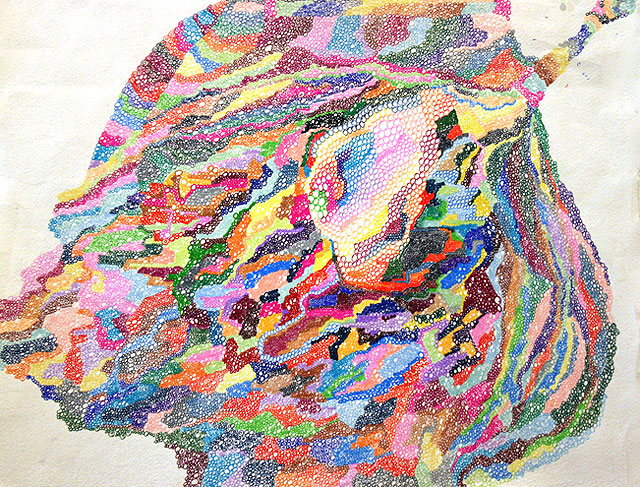

Buckwalter tries to console me in a way that makes it seem like this is a familiar refrain; contemporary artists come into the space and feel humbled. He says there are several magical elements at work at NIAD. “I don’t know where creativity lurks in anybody’s brain, but a number of NIAD artists are able to tap into that creative energy and make astonishing pieces. They’re able to do it frequently. They’re able to do it more frequently than me.”

“Here’s the darker secret,” he says. “You and I throw up limits to what we do and the limits are often economically based. I would love to hang a train from a crane in front of LACMA like Jeff Koons can, but I can’t afford that so I don’t even think that way. But at NIAD we provide the materials; we provide the space and the technical know-how. So, in a way, this frees the artists to be able to do more. I don’t have a benefactor saying here’s $3,000 for the next two months, do what you want. That’s one thing the NIAD artists don’t have to consider when they make their art. We explain to them that they shouldn’t lay down a monochrome field of oil stick and then try and put acrylic on top. We discourage them from wasting materials, but we encourage experimentation as much as we can. And that’s something that frees them up.”

I keep struggling with how often I see things at NIAD that I think have a bold use of color or a particularly brilliant conceptualization.

“We have 35 artists working in the studio every day. Is there any other place that you can go,” Buckwalter asks, “outside of Creative Growth or Creativity Explored where you can experience that much creative energy at one time? There’s not. So, just by sheer number, you’re going to experience something that’s just ‘Wow!’ If you and I rounded up 35 of our friends and put them into a space together, we would have a similar experience. It just happens that at NIAD we have so many creative people working together, including the teachers and studio volunteers, you can’t go wrong.

“Then there is the whole other magical part. The part that really draws me to NIAD’s art and our artists is how different their take on reality is from mine. I’m not the kind of person that likes to hear the same thing over and over. I don’t take comfort when people have the same opinions as me. I don’t want to round up a posse of like-minded individuals and go do something. I like it when everything’s different and I can experience something I never even dreamed of or thought about. And that’s the great strength of NIAD’s art, when you look at it you get this totally other take on reality.”

Buckwalter importantly rejects the term “outsider art,” which has been used to label and promote the work of artists like those at NIAD. He says, “Our artists are informed. They look at Art In America, they experience art (in field trips to Bay Area galleries and museums), and we bring work in from the outside for them to see. They’re not outside of anything anymore. I think that NIAD artists are commenting on the current moment as much as anybody else is.”

In fact, one of Buckwalter’s early realizations was that while some of NIAD’s artists were functional enough to go on field trips and see contemporary art in galleries and museums, three quarters of the artists weren’t, for whatever reason, able to do that. He says, “They experience contemporary art in magazines or books or newspapers. I went to art school and I know that the reality is when you experience art that way you don’t actually experience the scale of it or the tactile part of art. In your mind, you imagine it probably as the same size [as the reproduction]. Looking at a Clyfford Still painting in Art In America, the photograph is 4″ x 6″. You don’t realize that those things engulf you when you’re close to them, cause they’re gigantic. So I came up with the idea to invite contemporary artists into NIAD and use part of the gallery space to put their work up. When the studio’s artists come in every day they can experience some form of contemporary art in the physical world. They can get a sense of scale; they can get a sense of texture. Having the opportunity to introduce artists to other artists… I love it.”

This program gets strong reaction from the artists in the studio. In some cases it has changed the course of their work. For example, in a recent exhibition, Mercury 20 artist Kathleen King had a show of works she made from found pieces of scrap wood. Buckwalter describes them as “almost like Sean Scully paintings as wooden objects.” One of the NIAD artists, Jonathan Valdivias, looked at them for many weeks and then started to make his own version, which looks nothing like King’s. Buckwalter says, “I like the way that he filtered her work in a totally different way.”

So every couple of months, alongside a freshly curated show of NIAD artists’ work there is also a small show — often great — featuring the work of a non-NIAD contemporary artist. The dialogue inside the gallery is often amazing. If only people would go and check it out.

Buckwalter admits that one of the main obstacles he has experienced with the gallery is that Richmond as an idea is scary to people interested in art. “So, to get around that,” he says, “we’ve tried to stress that we aren’t part of the ‘Iron Triangle’ (the area of Richmond between two sets of train tracks where the majority of the city’s violent crime takes place). We also put everything up online so that people can see what NIAD is about. They can experience the personal stories of the artists and see them working. They can see the gallery. Now we’re doing online shows as well. Starting last week and it will be every week, I am inviting people in to organize a show of 12 pieces from our inventory of works on paper. It’s another way to get people engaged.”

The integrated program has paid off nicely. NIAD sells a lot of its artists’ work online and several of the studio’s artists have devoted collectors. Similar to most other gallery/artist arrangements, NIAD’s artists get half the money from sales of their work. A handful have also shown internationally. “Marlon Mullen is in the collection of The Studio Museum of Harlem and is in a group show there now. He has shown everywhere. Sylvia Fragoso is having a solo show in an outsider art museum in a suburb of Paris.” Don’t check your own C.V. against these accomplishments; it won’t do you any good. Just revel in your fellow Bay Area artists’ good fortune, and go to Richmond to see the art.

I Have Always Been a Storm runs September 13 – October 24, 2014 at NIAD Art Center, 551 23rd Street, Richmond, CA. The opening reception is Saturday, September 13, 12:30pm – 3pm. A That’s My Dog food truck will be in the courtyard serving sausages, chili dogs and more. For more information visit niadart.org.