Although in 1949 she was one of the first women to receive an MA in painting at UC Berkeley, Sonya Rapoport (1923–2015) is best known for her conceptual work, made with early computer programs. To those familiar with the Berkeley-based artist, Rapoport was a groundbreaking new media artist before the genre even existed. But her name might be new to many viewers, even here in the Bay Area; she was an artist who (like many of her gender) received more prominent attention later in life.

For those freshly discovering Rapoport’s work, Sonya Rapoport: Final Works at Krowswork (on view through Dec. 19) is a complicated place to start. But it’s a worthy starting point, as long as one keeps in mind that precise context matters.

This is not a retrospective. The exhibition presents work made during her residency at the alternative art center, representing the artist’s final works before her passing in June 2015. The exhibition also serves as an intimate homage to the artist’s life and works.

Final Works features two installations made during the residency and video documentation of earlier work. Perhaps predictably for conceptually-driven works, the backstory helps unravel complex layers of meaning. In 2014 UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library acquired Rapoport’s archive, triggering the artist to pore through her life’s work.

Although generally a self-reflexive artist, her final installations directly correspond with earlier pieces: The Transitive Property of Equality (2015) is the twelfth iteration of a work she began in 1979, Objects on My Dresser; Yes Or No? (2014-15) recycles archival visuals.

For the uninitiated, it’s useful to start by watching the video to get a taste of Rapoport’s modus operandi. She experimented with scientific ways to categorize, quantify and interpret highly subjective experiences, but in unpredictable ways. Her playfulness comes out in these interactive installations, like when she paired a unique (if then rudimentary) computer program for analysis alongside an on-site palm reader or philosopher to holistically analyze a personal topic.

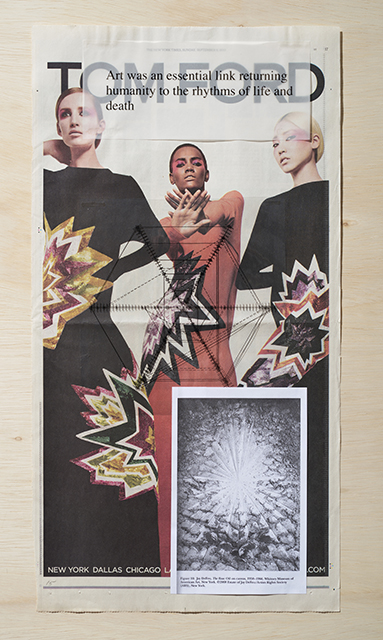

Exposure to her early work helps, too, when studying the collages of Yes Or No? One can then recognize the hand-gesture poems of Digital Mudra (1987), and the “shoe psyche” portraits from Shoe Field (1986) pasted onto pages of The New York Times, in addition to quotes from Richard Cándida-Smith’s writing on Jay DeFeo. Rapoport appropriated lines about the work of DeFeo, a classmate of hers at UC Berkeley, that she found applicable to and definitive of her own work. Rapoport’s tactic of repurposing shows up repeatedly in her practice, a trick that embraces individualized interpretation of information within established parameters.

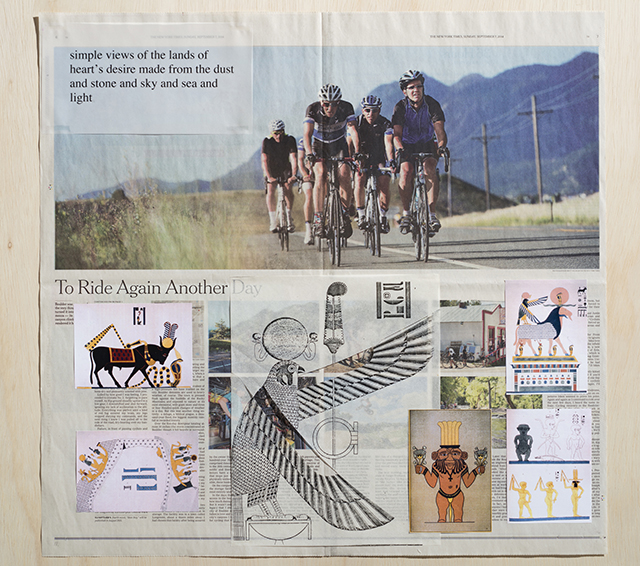

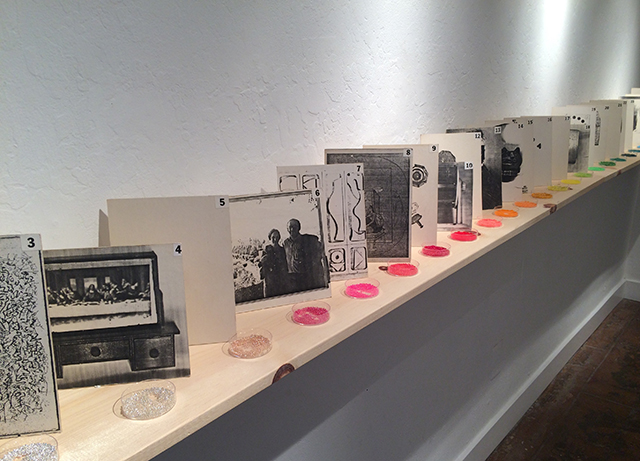

To that end, The Transitive Property of Equality (2015) asks viewers to interact with the endearingly humble objects Rapoport kept on her dresser. The items are displayed in the gallery, from a ceramic cat bank to a photograph of the artist’s daughter with her husband. Also displayed are photographs of the objects, lined up on a shelf, each accompanied by colored beads in petri dishes. Surrounding the walls of this room are, again, pages from The New York Times overlaid with text.

This time Rapoport appropriated words from a poem by Anne Lesley Selcer, a fellow Krowswork resident artist. To participate in the installation, viewers are instructed to individually match an image of a dresser-object with one of the poem lines; their choice is represented by depositing a bead into a 3D grid. (Having watched the video documentation of Objects on my Dresser, one can imagine Rapoport’s warm voice inquiring, “Now where would you like to put that?”)

Alongside the hyper-local references to the Krowswork residency and her own body of work, Rapoport’s practice extends to examine the idea of the public itself. Her repeated use of The New York Times as a canvas suggests a fascination with mass visual culture, that sea of information that surrounds individuals as they craft their own experiences. Rapoport continually studied her own navigation through public information, media, advertisements and even language itself.

Sonya Rapoport: Final Works functions as a capstone and a cliffhanger. Although the exhibition presents just enough of her early work that anyone can comfortably move forward into experiencing these last pieces, it’s clear that Rapoport’s work — early and final — is worth getting to know.

Sonya Rapoport: Final Works is on view at Krowswork in Oakland through Dec. 19, 2015. For more information, visit krowswork.com.