We don’t have any photographs of the 1876 Battle of the Little Bighorn. The large-scale dramatic paintings executed after the fact were based on eyewitness accounts — though at times, not even those. Distorted visual representations of “Custer’s Last Sand” appeared in “Buffalo Bill” Cody’s Wild West shows starting in 1888 and continued, with Errol Flynn playing a highly fictionalized (and dashing) Custer in the 1941 hit They Died with Their Boots On.

But in the low light of the Cantor Arts Center’s second-floor gallery, a true eyewitness account of the battle is on display in Red Horse: Drawings of the Battle of the Little Bighorn. The 12 graphite, colored pencil and ink drawings on blank ledger paper illustrate one man’s memories of the two-day battle. The artist is Red Horse, a Minneconjou Lakota Sioux warrior who experienced firsthand the victory of the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne and Arapahoe forces over the U.S. Army’s 7th Cavalry.

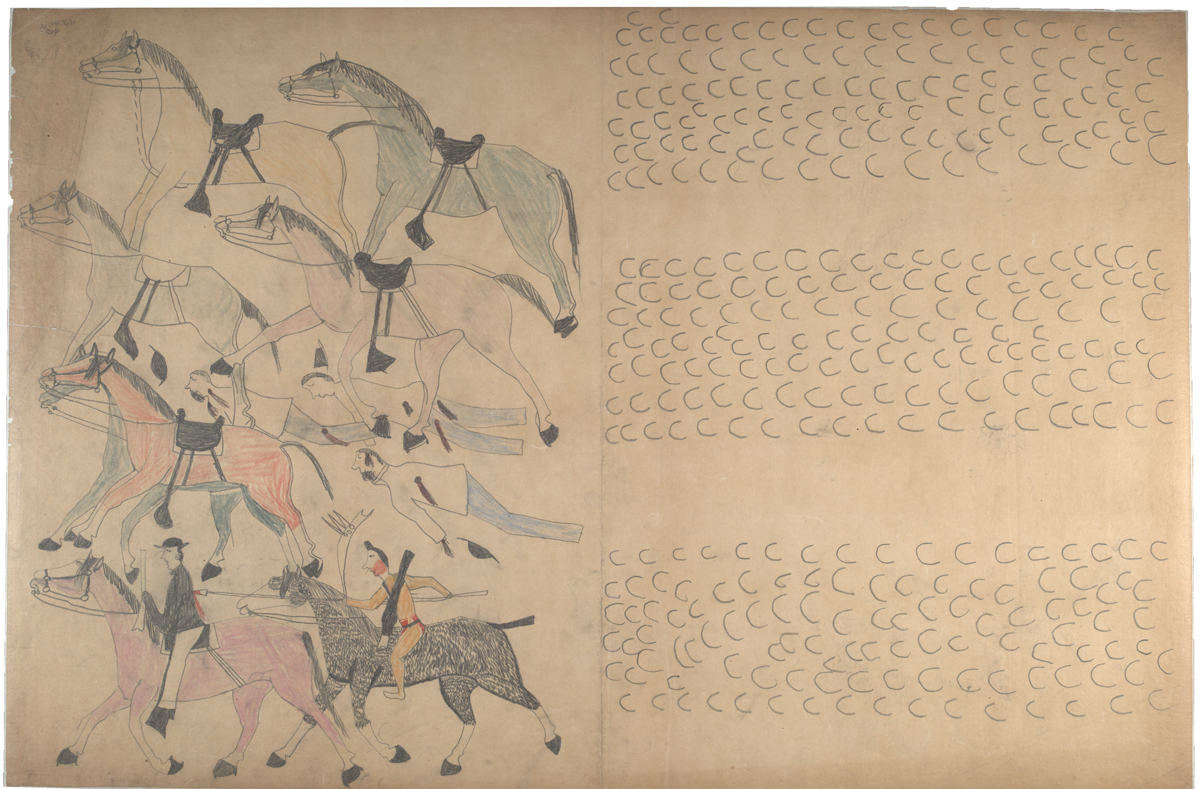

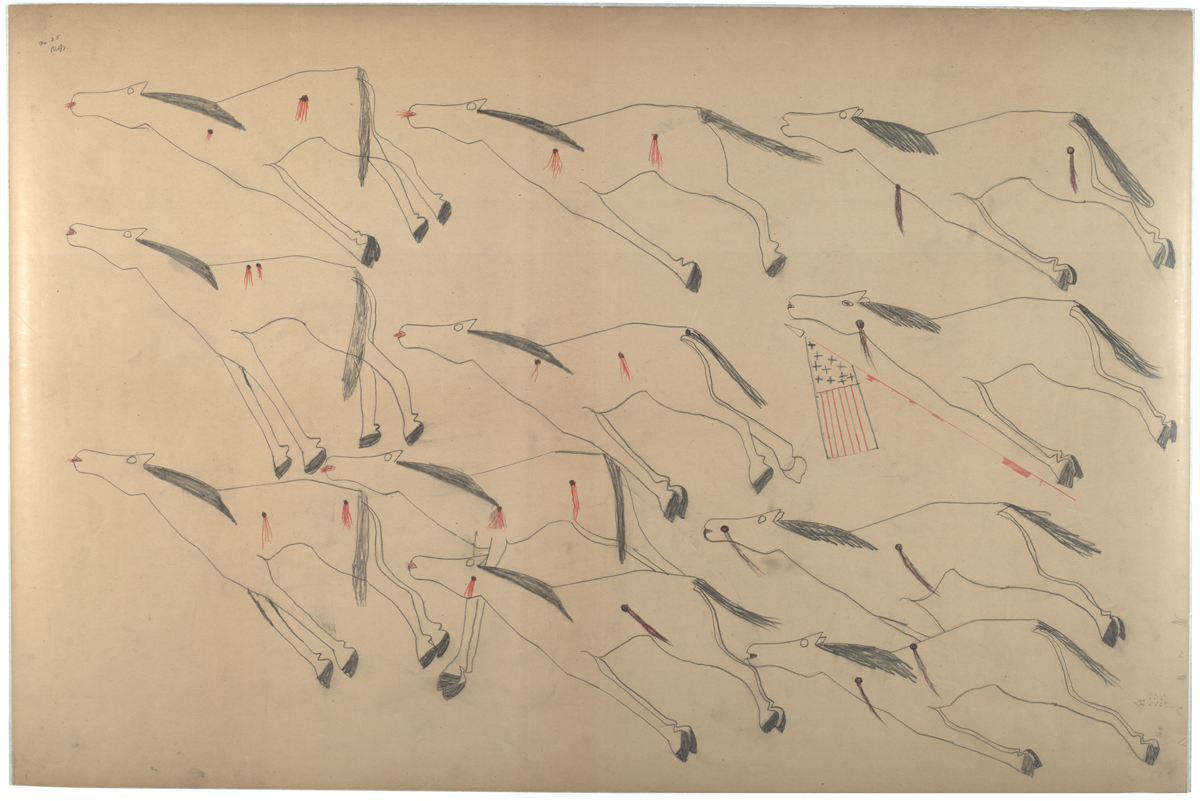

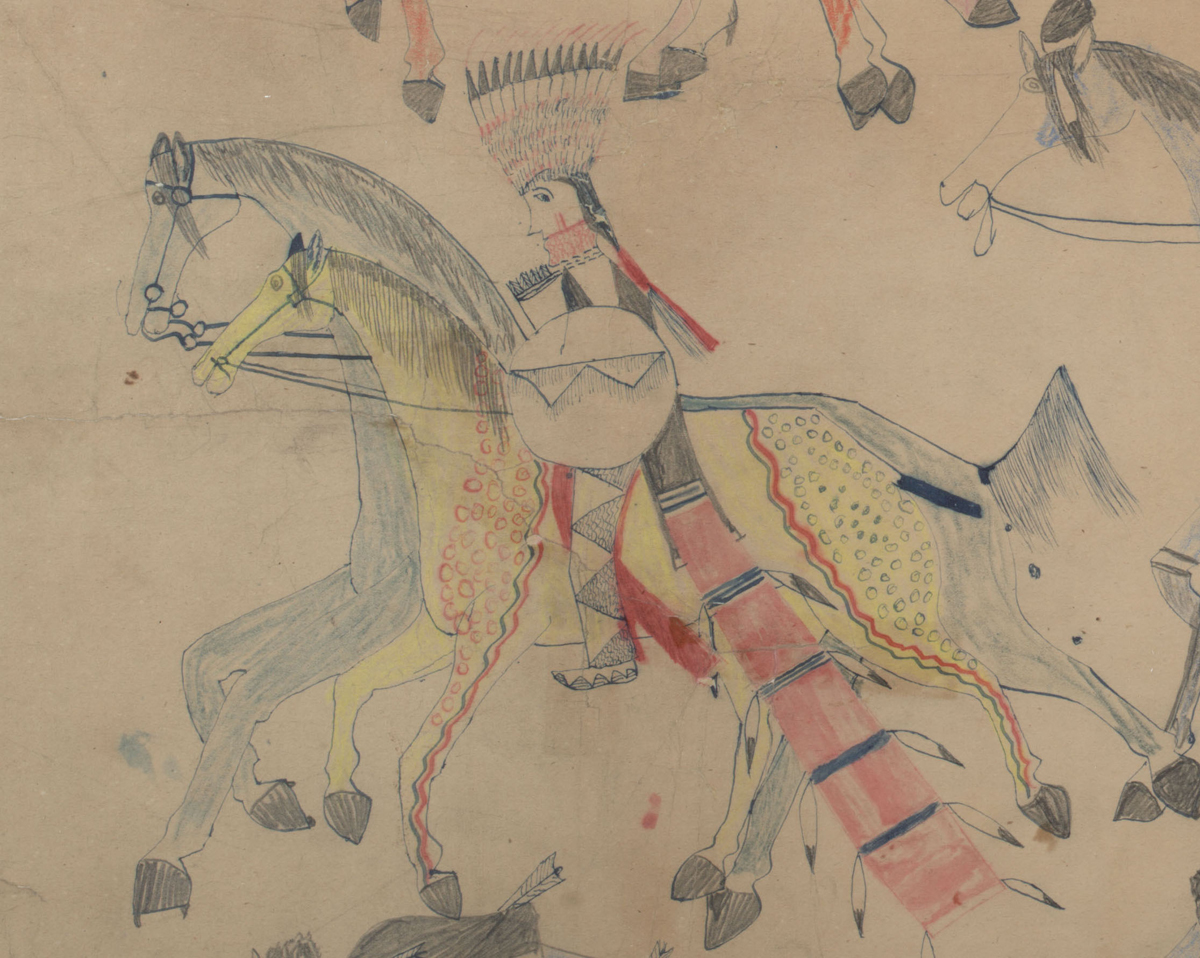

In wordless detail, Red Horse depicts uniformed cavalry soldiers advancing on horseback from right to left. Then, three orderly rows of tipis. Then, Native American warriors and hundreds of hoof tracks. The battle that follows is scene after scene of jumbled and extreme violence — both horses and men fall to the ground dead. In the final drawing presented at the Cantor, the victors — Native Americans carrying what were once cavalry rifles — ride their own horses bareback and lead what were once cavalry ponies (recognizable by their saddles and long tails) from right to left across the page.

Red Horse created the drawings in 1881 to accompany his sign-language testimony of the battle, a testimony likely gathered not for historical or artistic reasons, but for the Smithsonian’s Bureau of Ethnology 1894 study of Native sign languages and “Picture-writing of the American Indians.” His 42 drawings entered the Smithsonian Institution’s National Anthropological Archives and remained there for 135 years, leaving storage only a few times for short exhibitions.

“They’ve just been in drawers,” says Stanford senior Sarah Sadlier, a student research assistant who was integrally involved, along with her professor Scott D. Sagan and Cantor curator Catherine Hale, in selecting the drawings now on display at the Cantor. Sadlier, like Red Horse, is Minneconjou.

Red Horse’s eye for detail is unsparing. Soldiers sport different styles of facial hair. A white man in civilian clothes — potentially Custer’s brother or nephew — lies dead near an upside-down American flag. He captures differences in garb and decoration, but also the gory realities of battle: fallen soldiers on both sides, dismembered limbs, scalped bodies and an entire page devoted to dead cavalry ponies.

In Red Horse’s depiction of what is commonly referred to as “Custer’s Last Stand,” Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer is notably absent. Instead, war is front and central, repeated like the hoof prints covering three of the drawings on display.

“The ledger art produced about the Battle of the Little Bighorn was often Custer-centric,” Sadlier says. “Many artists didn’t want to draw what they saw because they feared retribution. There are no ledger art drawings I’ve seen that are so violent and true to the face of battle.”

Viewed in chronological order, Red Horse’s drawings are a retroactive storyboard for a perspective that doesn’t figure largely in the mythology of the battle as it was long depicted, let alone the story of the American West. For Sadlier, tracking down information on Red Horse in the national archives led to personal discoveries as well as historical ones.

It turns out Red Horse and Sadlier’s great great grandmother lived near each other on the Cheyenne River Agency, where Red Horse died in 1907. Red Horse gave his battle testimony twice — once in 1877 and again in 1881, when the ledger drawings were produced. Looking at the earlier records, Sadlier uncovered another piece of buried history: “I discovered that no one knew who the interpreter was for the 1877 account,” she says.

The interpreter put forward by historian W. A. Graham started learning Plains sign language just months before Red Horse delivered his testimony. His skills wouldn’t have been up to snuff. The true interpreter of Red Horse’s first account of the Battle of the Little Bighorn could be, coincidentally, another one of Sadlier’s ancestors: John “Big Leggins” Bruguier.

“It could be someone we just don’t have the name for,” she admits, “but he could be a contender. It was a very rewarding and unexpected experience to potentially find my own family history in this project.”

Red Horse: Drawings of the Battle of the Little Bighorn is on view at the Cantor Arts Center in Palo Alto through May 9, 2016. For more information visit museum.stanford.edu.