If you’ve glimpsed the new Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive logo — a blue conversation bubble of sorts, with the brightly-colored letters BAMPFA situated at its center — you may have noticed more than just a typography shift. The slash that once separated the museum’s acronym from the film archive’s is, like the walls that separate buildings, gone.

BAM programming ended in the beloved Mario Ciampi building in December 2014; the PFA Theater closed up shop in its temporary location this past August. Now, upon BAMPFA’s reopening this week, for the first time in over 15 years, art viewers and theater-goers will use the same entrance to attend their respective cultural happenings: 2155 Center Street, just a block from the Downtown Berkeley BART station.

Designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro (responsible for the new Broad Museum in Los Angeles and the upcoming MoMA expansion project in New York City), the new BAMPFA building adapts an existing UC Berkeley printing plant into a combined home for both institutions. The plant, what architect Charles Renfro calls an “art moderne machine-age shed,” was excavated below street level to double the floorplan, thenwrapped with a torqued stainless steel-clad form.

The result is both familiar and futuristic. Inside, the torqued space houses the 232-seat Barbro Osher Theater and a new home for Babette Cafe that cantilevers out above the museum’s front entrance. Snacks can now be consumed while gazing over the walls of the street-level galleries. That’s a good thing — said snacks will be necessary to fuel visitors’ progress through the initial exhibition, Architecture of Life, which easily fills every one of the new museum’s 25,000 square feet of gallery space.

Though wall text announces the exhibition in several places, there is no true start or finish to BAMPFA director Larry Rinder’s inaugural show. Themes, media and methods connect one room to the next, making the process of touring the exhibit one of pleasurable, personal discovery.

Architecture of Life, though wide-ranging and diverse, with over 250 works, never feels overwhelming. The exhibition points to the ways in which humans identify and create structure in the world around them. The connections between individual objects and the curatorial theme are often loose, but the connections between the works themselves create a thrilling web of associations and “aha!” moments.

The piece that best encapsulates this feeling (and elicited a barely-contained chortle of joy from me) is a framed paper chart of radio signals detected by Jerry R. Ehman on Aug. 15, 1977. While working on a SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) project at Ohio State University, he noticed a recorded signal with characteristics of a nonterrestrial and non-Solar System origin. An excited Ehman circled the irregular sequence of letters and numbers in red pen and, in loopy cursive script, wrote “Wow!” beside it. The signal has not been found again since.

Architecture of Life is filled with stories of ingenuity and invention. Detailed wall text relays tales of characters like Bernard Palissy, a 16th-century Frenchman who held the title of “king’s inventor of rustic figurines” and also correctly identified the origin of fossils. Then there’s Viktor Schauberger, a 20th-century Austrian forest caretaker who wanted propellers to slow things down, not speed them up. I filled my notebook with names of interesting-sounding people and artists I’d never seen before. Favorite works from this list include Suzan Frecon’s abstractions, delicate works by Ganesh Haloi and Robert Overby’s 1972 piece Broken Window Maps.

Overby’s series of 18 canvas panels, shaped after the windows of the crumbling Barclay House Hotel in Los Angeles, are matched perfectly by a group of black and white photographs directly across the main gallery space — Gordon Matta-Clark’s Window Blow-Out, a 1976 series documenting broken windows in an abandoned Bronx housing project. I let out another appreciative sound.

Again and again throughout the exhibition, Rinder creates formal pairings between disparate works: a Turkish Islamic prayer rug opposite an Ad Reinhardt black painting; Qiu Zhijie’s massive imaginary map of The World Garden opposite Chris Johansen’s cluttered Cityscape with House & Gray Energy. Alternatively, the exhibition gently guides viewers through the evolution of artistic forms; intricate Pomo baskets sit next to Ruth Asawa’s wire sculptures hanging next to Buckminster Fuller drawings of woven spheres.

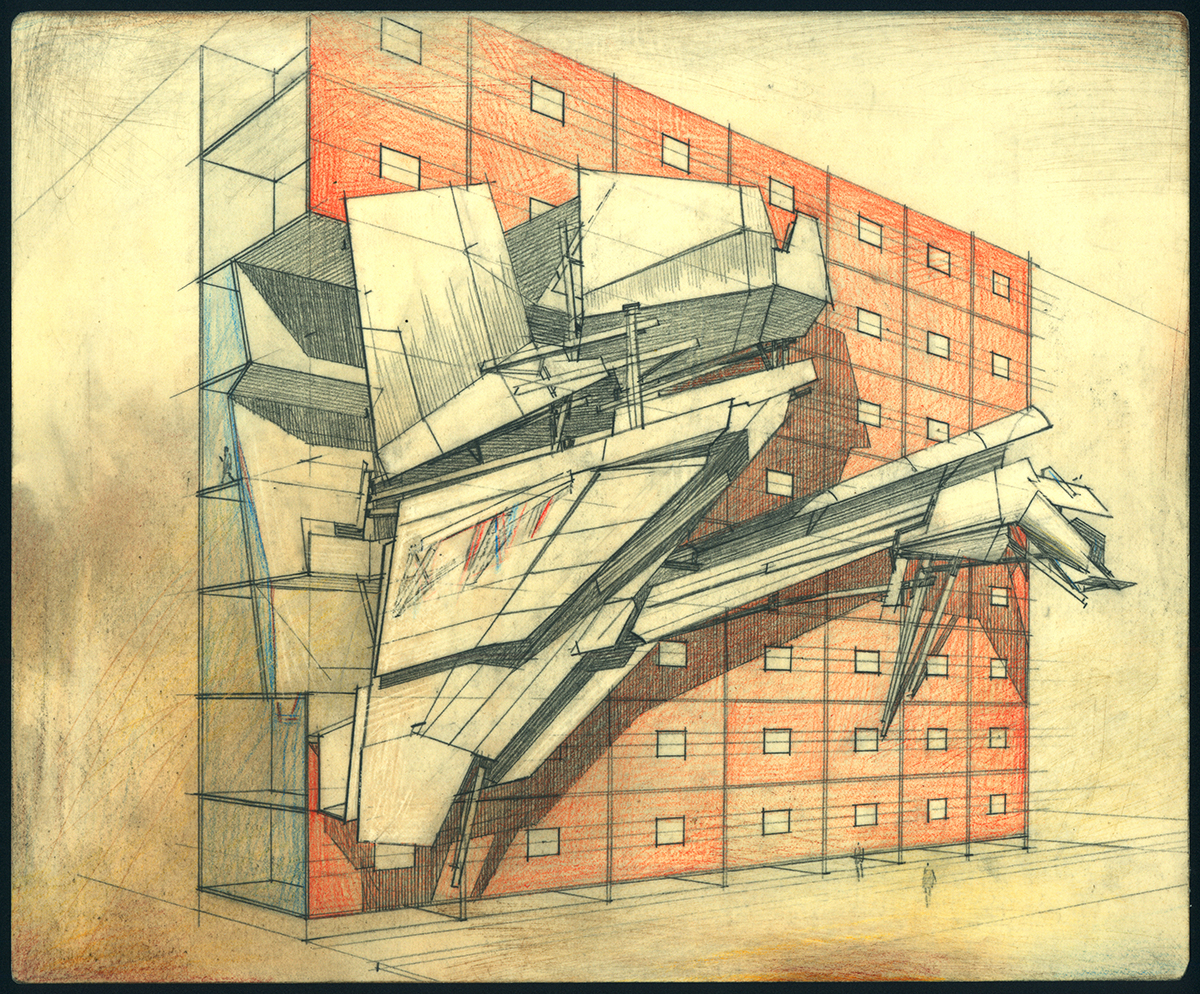

The entire exhibition is filled with objects of such awe-inducing beauty that the last stop on my personal route through the galleries felt a bit like an afterthought — a room containing video work made with Palestinian refugees, post-tsunami architecture in Japan, and Lebbeus Woods’ designs for architecture built out of the destruction of war. There is structure in conflict, and there can be art despite conflict, but Architecture of Life prefers to depict a more fruitful collaboration between humans and the world as a whole. And for the grand opening of the new BAMPFA, who can blame them for a little optimism?

Architecture of Life opens to the public Jan. 30 and is on view through May 29, 2016. The Pacific Film Archive opens on Feb. 3, 2016 with Cinema Mon Amour. For tickets and more information visit bampfa.berkeley.edu.