Chinese artist and antagonist extraordinaire Ai Weiwei came to the attention of the western art establishment as the market for contemporary Asian art flourished beginning in the late 1990s. Ai has distinguished himself as a multi-disciplinary practitioner, working with photography, sculpture, design, architectural principals, and social networking platorms from a conceptual yet deeply critical perspective. For his work, for his opinions, Ai has endured intimidation, police raids of his studio, imprisonment, and beatings from the Chinese government, yet he prevails.

On September 27, a site-specific installation of new work entitled @Large: Ai Weiwei on Alcatraz will open under the direction of San Francisco gallerist Cheryl Haines, the For Site Foundation, and the National Parks System. Building on the success of International Orange, the 75th anniversary celebration of the Golden Gate Bridge that was mounted by For Site in 2012 and received wide spread praise, @Large considers the dimensional and contested history of Alcatraz Island as a military installation, a prison, confiscated Native American land, and now as a tourist attraction and protected space within the National Parks System.

Before you don windbreakers for the chilly ride out to Alcatraz, take a few minutes to learn about or brush up on a few other objects, exhibitions, and interventions that sustain Ai Weiwei as a “person of interest”.

Clik here to view.

1. Instagram and Twitter feed (ongoing)

Ai Weiwei has made the most of social media in connecting with his audience and subverting the Chinese government’s attempts to silence him. As we know, access to and use of the Internet is heavily regulated in China, so it is remarkable that the artist manages to transmit missives with any regular frequency. It is the ongoing dialogue, which verges on messianic messaging at times, that makes this aspect of his practice both engaging and troubling.

Clik here to view.

2. Beijing National Stadium (the Bird’s Nest) (2003-2008)

Constructed as the central venue in which the 2008 Summer Olympics and Paralympics in China were held, Ai worked as part of the team that included the esteemed Swiss architectural pair Herzog & de Meuron to create the space in which the excitement of the Games unfolded. The structure is an architectural and engineering marvel. The design, which emerged after the working group studied aspects of Chinese ceramics, includes a rainwater collection and purification system, subterranean pipes which heat and cool the stadium, and latticework steel beams masking supports for a retractable roof that was ultimately abandoned in the final design. Speaking to a Japanese news agency in 2012, Ai stridently distanced himself from the project, citing intense frustration with China’s human rights violations years before and in the lead up to the Games, and the sense that his position on the international stage was exploited.

Clik here to view.

3. Sunflower Seeds (2010)

Covering completely the floor in the Tate Modern’s massive Turbine Hall as part of the Unilever Series in 2010-11, Sunflower Seeds consisted of millions of porcelain “seed husks” which appear at first glance to be identical, but are in fact unique, hand-crafted objects. Painted by craftsmen and women working in the city of Jingdezhen, the production and display of the seeds brought audience attention to issues of consumption (Western taste for Chinese porcelain and other goods) and identity (the anonymity of Chinese artisans and workers across the industrial landscape who struggle under the boot of obscene production demands and working conditions). In a spectacularly ironic turn, Tate administrators closed the installation to the public shortly after it opened due to concerns that dust kicked up by those walking on the seeds would exacerbate respiratory problems. When the exhibition reopened, it was only visible from a bridge high above the gallery floor. For a brief moment, visitors to one of the world’s preeminent museums for contemporary art and anonymous Chinese artisans stood on common and decidedly unhealthy ground.

Clik here to view.

4. Remembering (2009)

Installed on the facade of Munich’s Haus der Kunst as a part of the retrospective exhibition So Sorry, Remembering was composed of 9,000 children’s backpacks and spelled the phrase in Mandarin characters “She lived happily for seven years in this world.” The quote, uttered by a mother who’s child died in one of the many poorly constructed schools that were leveled by the 8.0 earthquake that rocked Sichuan province in May 2008, commemorates those needless deaths and illuminates Ai’s ongoing denouncement of the Chinese government. Beginning in December 2008, Ai listed the names of the dead children on his website and by May 2009, the one-year anniversary of the catastrophe, the list had ballooned to 5,385. Outside of China, it is widely believed that Ai’s exposure of ineptitude and corruption at the state level brought the near-full brunt of the government’s wrath down upon his head.

Clik here to view.

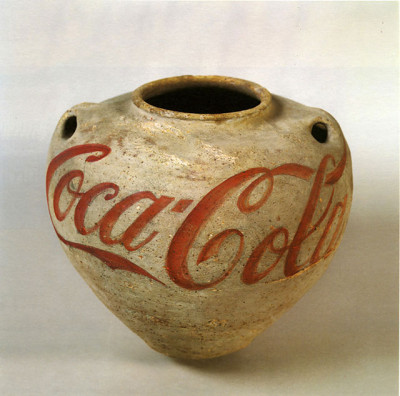

5. Han Dynasty Urn with Coca Cola Logo (1994)

Ai Weiwei lived and studied in New York for 13 years before returning to Beijing in 1993. One year later, he purchased an assortment of urns produced during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) and painted one of them with the familiar Coca Cola logo, an act that prioritized Ai’s interest in the readymade and reflected both the time he spent immersed in the western cultural/artistic milieu and his skeptical view of globalism. Ai’s alteration of the urn also visualizes his desire to overcome staid notions of Chinese art as purely historical, the erasure of skilled labor over the course of centuries, and notions of “fake” vs. “original” in art collecting.

Clik here to view.

6. Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995)

In a large photographic triptych, Ai is photographed holding and then dropping a Han Dynasty urn. His near-placid facial expression is a pointed contrast to the destruction that unfolds by his act. For many western antique collectors, the urns represent historical significance and a demonstration of wealth. For others, including Ai, the urns represent the stranglehold of history and tradition within Chinese culture that must be questioned and perhaps, as the sequence suggests, fractured outright.

Clik here to view.

7. Venice Biennale 2013: Straight

Ai Weiwei made his first appearance at the Venice Biennale in 1999 when he and 20 other Chinese artists were selected to represent their country in what is arguably the art world’s most prestigious fair. Appearing in 2007 and again in 2013, Ai debuted three installations that criticized the Chinese government in no uncertain terms. Straight comprises 150 tons of twisted rebar that was retrieved from sites impacted by the earthquake that rattled Sichuan and then restored to their original state. The stacks spread wave-like across the gallery floor, creating a somber landscape that memorializes the dead and visualizes the frustration of those who struggled to put things right in disaster’s wake.

Clik here to view.

8. Venice Biennale 2013: S A C R E D

Arrested in April 2011 and held for 81 days for alleged “economic” crimes including fraud, Ai’s imprisonment was widely understood both in and out of China as the government’s way of silencing the artist for speaking against the state for a litany of administrative violations. S A C R E D is a series of dioramas that visualize Ai’s experience of incarceration, specifically the 24/7 monitors – human and electronic – that watched his every move. As visitors to the Biennale discovered, peering into the hulking 5×12 foot iron boxes enacted the same lurid scopic thrill enjoyed by his captors. Installed in the Church of Sant’Antonin, arguably one of the most serene environments in Venice, the dioramas reenact in muted tones the trauma to which Ai and countless other Chinese dissidents are subjected.

Clik here to view.

9. According to What? (2013 – present)

A large retrospective of Ai’s work currently traveling between venues in the United States and Canada, According to What? is the first major exhibition of Ai’s work mounted in the west. Objects on view date mostly to 2008 and after, when the artists’ political dissent and creative output reached a fevered pitch. This is the first opportunity most museum audiences have had to experience his work collectively, and at each venue, attendance has been overwhelming.

Clik here to view.

10. Circle of Animals: Zodiac Heads (2011 – present)

The Chinese zodiac is populated by familiar animal figures including the horse, the rat, and the dragon. Ai’s project, the first major sculptural endeavor of his career, is based on the heads created for the imperial retreat at Yuanming Yuan and the looting of the palace by British and French troops in the 1860s. Ai considers looting vs. notions of paternalistic “preservation” as they were advanced by colonial agents in Asia.

As this brief list suggests, Ai Weiwei is a dynamic and controversial artist. What do you think about an installation of his work at one of San Francisco’s most popular tourist sites? Feel free to leave your thoughts in the comments section.