The music tells a dramatic story. First, we’re zooming through the empty chill of space, then homing in on our little blue-green Earth just before the industrial age, with bird songs mixed with violin and trance inducing electronic music. And then the planet starts to warm up, a lot, and the music gets faster, stranger, and more dissonant.

That’s the score for the Climate Music Project, a music-and-video piece about the causes and effects of global warming that will be performed for the second time on Friday, Feb. 19 at the Chabot Space and Science Center in Oakland.

Climate Music Project founder Stephan Crawford is a sculptor with a studio in San Francisco. When I interviewed him earlier this month, I asked him why music, when his natural medium is wood and stone?

“The mission was to pursue a hearts and minds approach,” Crawford said, “and music is a universal language,” with the power, Crawford hopes, to move people to action in a way the facts alone cannot.

So Crawford created an unlikely coalition of scientists and artists.

“It’s really all modes of communications and all hands on deck at this point,” said William Collins, one of Crawford’s two climate science collaborators from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. “And to see whether or not we can make people understand that we do have a choice. But we must make a choice. And we have only a couple of decades in which that choice is still open to us.”

For the music, Crawford turned to composer Erik Ian Walker.

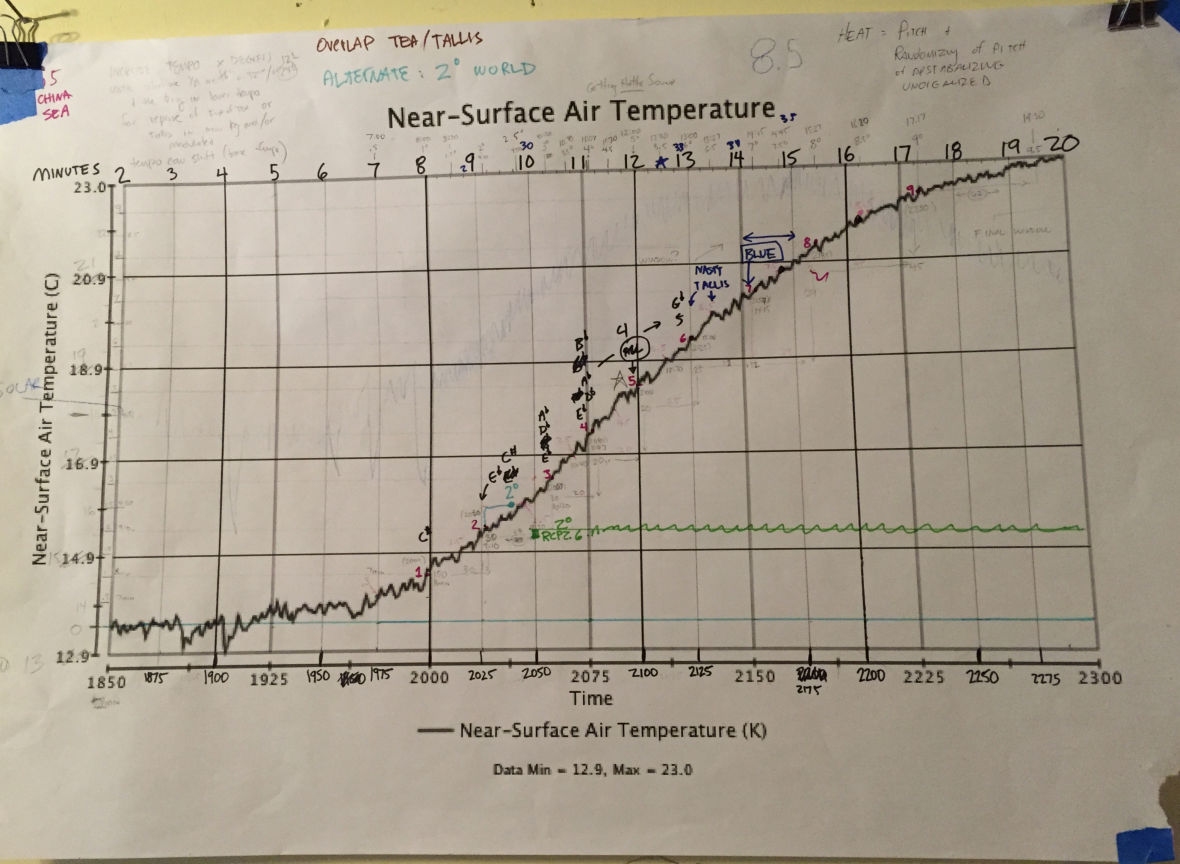

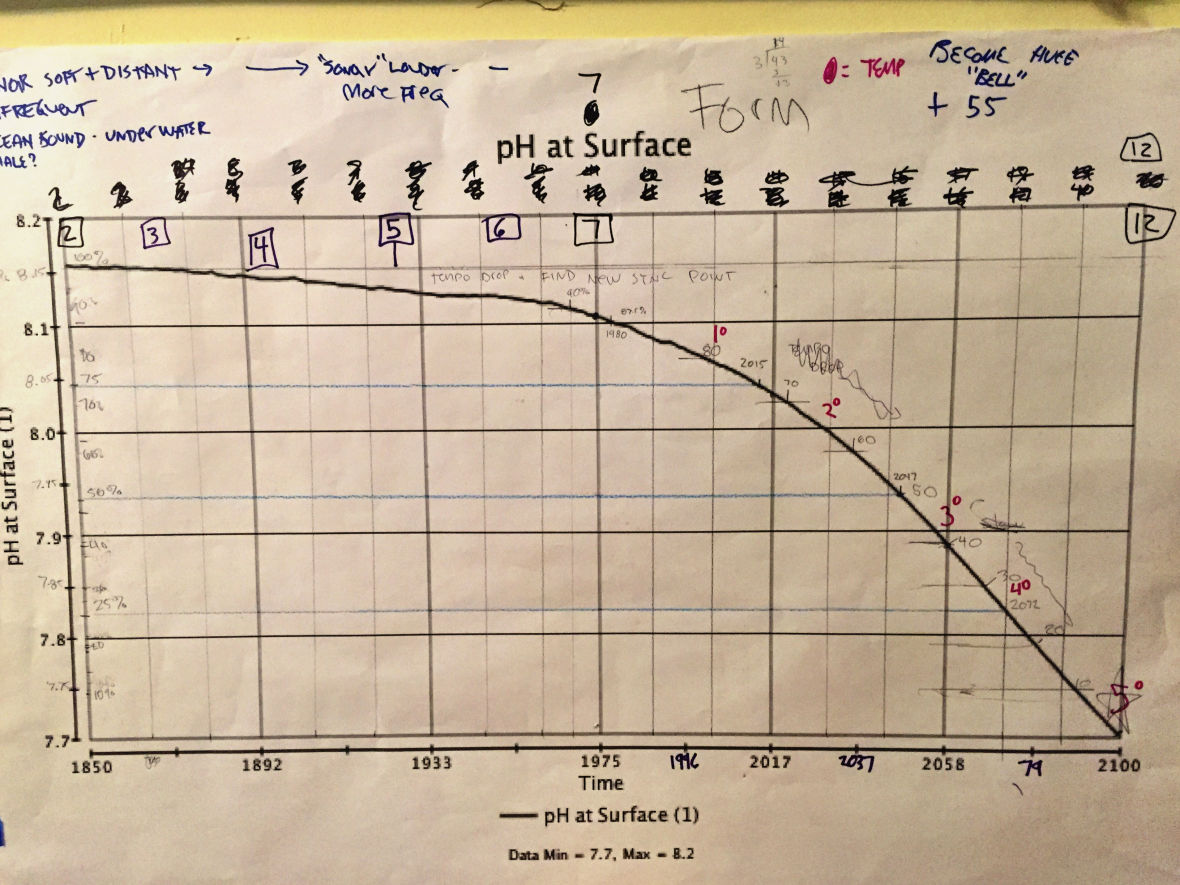

While sitting at the piano in his San Francisco studio, Walker explained to me how the data determined the music’s sound. Collins and his colleague Andrew Johnson provided Walker with graphs showing the changes in four key climate factors over a 500-year span, starting in 1800, at the dawn of the industrial age, and finishing in 2300, in a worst case global warming future.

CO2 controls tempo, temperature rise controls pitch and harmony, solar radiation controls distortion and density, and ocean PH controls form.

“As the CO2 is increasing, the piece starts going faster,” Walker said. “At first that seems okay, it’s speeding up in a way that feels good. And then there’s a point when it’s speeding up by hundreds of BPM, beats per minute. So it spirals out of control, by the time it’s five degrees up. And we’re going to end up at nine and a half.”

Walker played ,e a few bars from the score on the piano, then gave an atonal twist to the chords. “It’s the one example in my whole life,” he said, “where I’ve done a piece where as you’re increasing dissonance, people stay engaged, because they’re watching this thing that is illustrating a potential reality.”

And a scary one.

Music has often played a role in political and social movements. Songs like “We Shall Overcome,” and “I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag” (by Berkeley’s Country Joe McDonald) helped fuel the civil rights and anti-Vietnam war movements respectively. And music has long celebrated the beauty and power of nature. Think of The Four Seasons by Vivaldi, “Mother Nature’s Son” by the Beatles, or just about anything by French composer Olivier Messiaen.

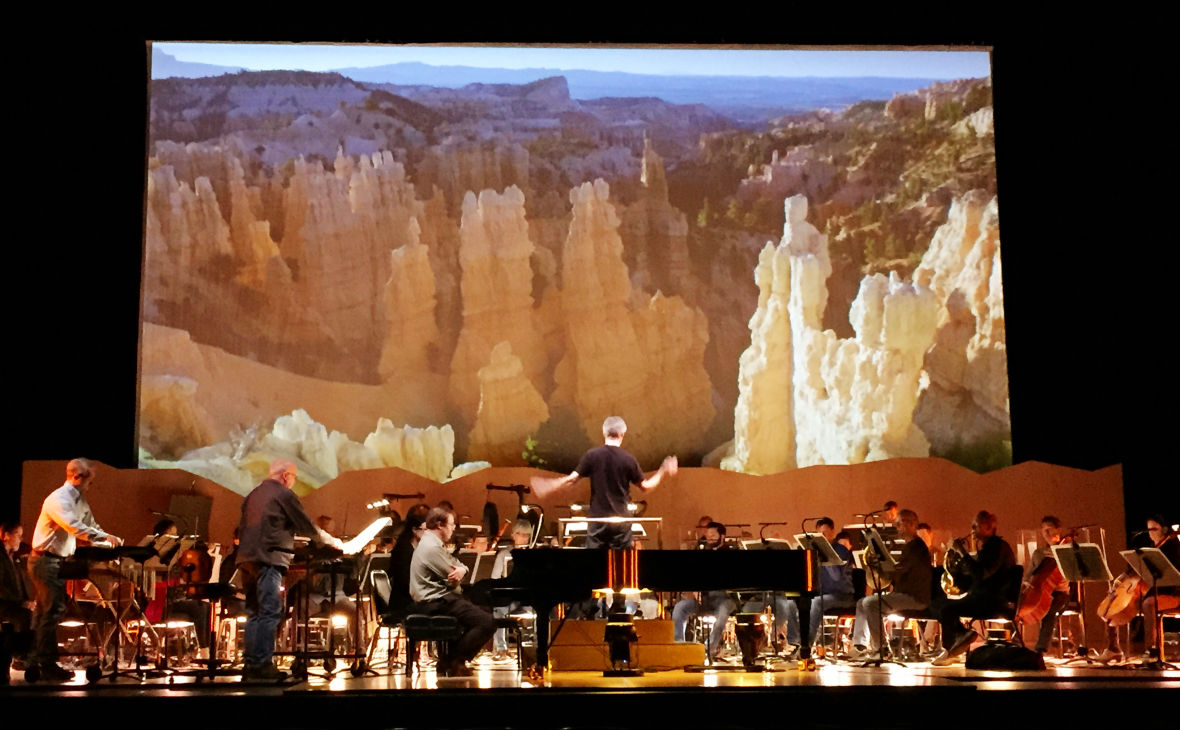

Conductor David Robertson recently led the St. Louis Symphony in a performance of Messiaen’s Des canyons aux étoiles at Cal Performances in Berkeley. It’s a 90-minute tribute to the red rock canyons of Utah, which Messiaen visited for the first in the early 1970’s.

Robertson knew Messiaen, and he says the composer didn’t include any explicit message in the music — certainly not about climate change, an obscure concern when Messiaen wrote Canyons in 1974.

“He was just trying to reflect what he saw,as outstanding beauty in landscapes unlike any other,” Robertson says.

The concert, which was commissioned by Cal Performances, also featured a video essay by Berkeley landscape photographer Deborah O’Grady, who spent months shooting in the same Utah canyon lands that Messiaen had visited 40 years earlier.

And O’Grady says she very much had climate change on her mind., pairing beautiful images of hoodoos and canyons with others showing people’s rude impact on the landscape, with the hope of inspiring social change through art.

“Our current age to me is the age of the oil,” O’Grady said, “and If I have a chance to influence anyone. Even one person. Then it’s worth doing.”

None of the artists I interviewed expect audience members to go home and sell their car or lobby their lawmakers about climate change, though they might applaud that move. But a concert can evoke a strong emotional reaction. Climate Music’s Stephan Crawford said he felt the music was having an impact, after hearing one woman speak in the forum after the project’s first performance.

“She said, ‘You know I was listening to the music and looking at the years count up,'” Crawford recalled, “and she said, ‘That’s when I was born. And that’s when my daughter was born. And that’s when my granddaughter will be born.’ And she was really putting the data in the context of her own life.”

The Climate Music Project presents a show at the Chabot Space and Science Center in Oakland Friday (Feb. 19). Cal Performances continues its exploration of the natural world May 1 with San Francisco’s Kronos Quartet playing Terry Riley’s Sun Rings.