It started as a day trip and ended with searches on Zillow. We — visual arts editor Sarah Hotchkiss and KQED Arts contributor Lakshmi Sarah — had lofty goals for our sojourn to Vallejo. We would take in the local flavor, visit arts organizations, meet artists, tour some studios, eat lunch and be back on the road by 3pm.

We had no idea what we were getting into.

The impetus for our trip was a deluge of messages in response to our Oct. 2015 map of recently closed, relocated or opened arts spaces in the Bay Area. “I will say, from my experience as well as the experiences of other artists that I know and work with, Vallejo is the burgeoning art community you are looking for,” wrote Cate Muzaffar. “We are having an art explosion in Vallejo!” wrote Sherry Tobin.

Well, alright then, we said, if the community we didn’t know we were looking for is just 30 miles away, let’s go check out this explosion.

Vallejo: City of Opportunity

Vallejo might be best known for declaring bankruptcy in 2008. Until Stockton followed suit in 2012, Vallejo was the largest city in California to do so. The stigma from this badge of dishonor is still tangible, but the city is making strides to achieve economic stability — even growth — four years after a federal judge released them from their Chapter 9 status.

Today, the city’s population hovers around 120,000. According to the 2010 census, the demographics break down to 25 percent white, 22.1 percent Black, 22.6 percent Hispanic or Latino, and 24.9 percent Asian. The largest employers in Vallejo are Kaiser Permanente, Six Flags Discovery Kingdom (yes, the theme park) and the Vallejo Unified School District.

But we drove there to talk to a different subset of the community — the artists, the makers, the publishers, the experimental concert organizers — those able to hold court in their garage, community arts center or decommissioned naval base in the middle of a Thursday.

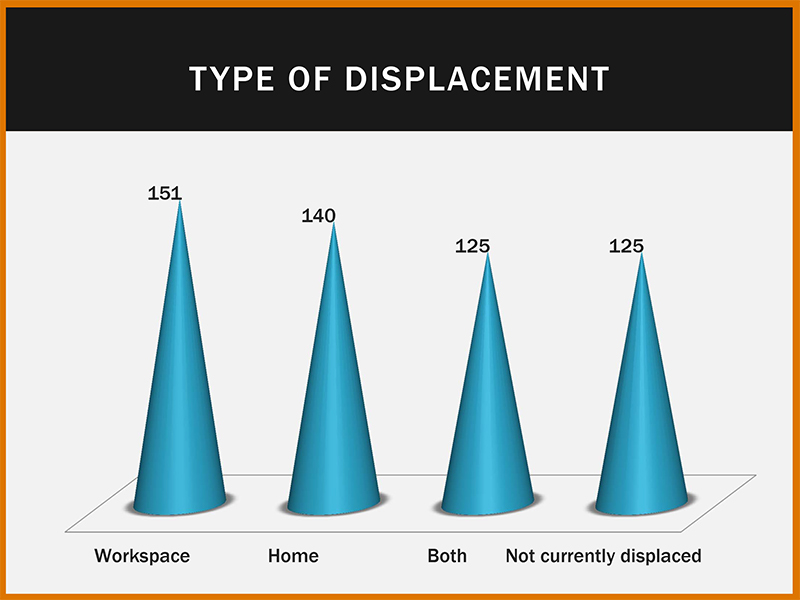

We wanted to know if Vallejo offers a viable alternative to eking out art practices in cramped (yet bustling) cities with astronomical rents. And this wasn’t just a personal quest. In September 2015, when the San Francisco Arts Commission surveyed individual artists about their space needs, 28 percent of respondents had been or were being displaced from their homes, 26 percent from their studios and 23 percent from both. Vallejo was a litmus test: Can an arts community grow and flourish in a remote city still recovering from bankruptcy?

The numbers were promising. According to the housing site Zumper, average rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Vallejo is $1,100; in Oakland that jumps to $2,210 and in San Francisco, it’s a cool $3,490. In the same SFAC survey, artists pay an average of $1.75 per square foot for their studio spaces. In Vallejo’s Coal Shed Studios, one of the city’s largest complexes of artists’ working spaces, the average rate is $1 per square foot, a price that was set 10 years ago.

With all these figures rumbling in our heads, it didn’t take as long as we expected to drive up I-80 from Oakland, across the Carquinez Bridge and into downtown Vallejo. “It’s so close!” we said to each other with surprise.

A Super Classy Garage

Trees making the shift from green to red, orange and yellow lined the streets. Winding up a hill on the east side of town, we arrived at the home of Super Classy Publishing, a nondescript ranch style house on a suburban street that could have been anywhere in the Bay Area.

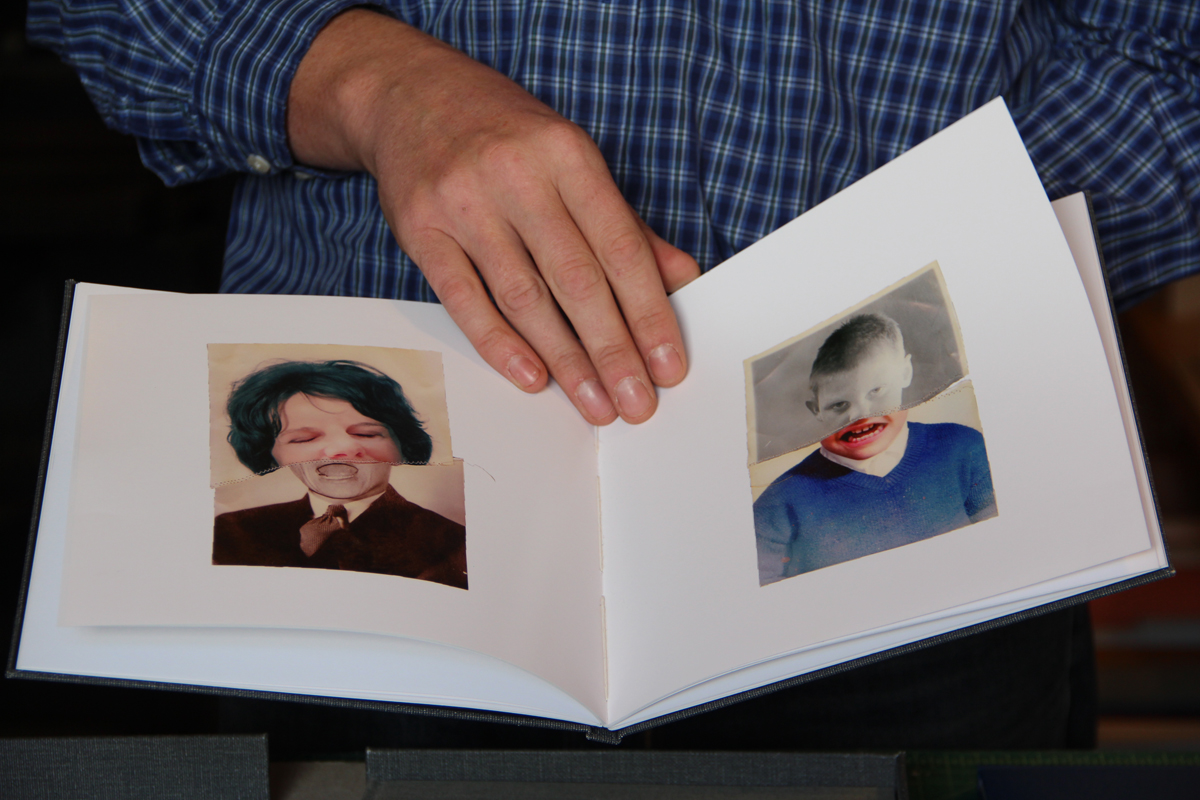

It is also the home of Andy and Katie Rottner, who have turned their garage (“Who needs to park their car in their garage?” says Katie) into a small publishing operation. The couple moved to Vallejo from Oakland in 2013, finding a house with plenty of space for both their young family and their studio, not to mention sweeping views of the city and San Pablo Bay. Making meticulous cloth-covered boxes and limited edition artist books — many one-of-a-kind — the Rottners carve out a supplemental income doing what they love.

While Katie works from home as a marketing copywriter, Andy teaches bookbinding at the San Francisco Art Institute and San Francisco Center for the Book, commuting several days a week into San Francisco. He often takes the ferry, which he deems “very civilized” in comparison to the “very grim” stop-and-go highway traffic during commuting hours.

Relative newcomers to the city, the Rottners also feel a bit disconnected from the local arts scene. Their clients come mostly from San Francisco and the East Bay. “I wish we were better connected to the day-to-day art world in Vallejo,” said Andy. “I think the art world here is super grassroots. People are very prideful about it, but there’s no central forum.”

“Well the Hub is sort of that,” said Katie.

Speak of the devil, we said — we’re going there next.

Hubbub at the Hub

At the corner of Georgia and Marin Streets in downtown Vallejo stands Odd Fellows San Pablo Lodge #43, home to the city’s longstanding chapter of the community-minded social club.

“Since the 1990s, downtown Vallejo has slowly turned into a near-ghost town, with empty storefronts lining what was once the booming main street of Vallejo,” the lodge wrote on its Facebook page in August 2013. “We need to bring business and life back to downtown.” With that, the order’s ground-floor retail space transformed into the Hub, a multi-purpose space hosting workshops and events, selling artists’ wares and providing a gathering space for arts enthusiasts of all ages.

When we arrived, the Hub was bustling. Easily two dozen people roamed through the displays of art, crafted objects and jewelry. It wasn’t just a crowd of casual shoppers; everyone clearly knew each other. Realization dawned: They were all here to meet us.

Word had spread through Ric Duran, a self-described “volunteer junkie” active with a wide variety of Vallejo organizations. Duran told us he made more friends in six months of living in Vallejo than he did in six years of life in San Francisco. The crowd he’d gathered was tangible proof of that.

Over the next two hours we talked to everyone — from the “oldest living Vallejo artist” to the president of the Vallejo Symphony. If the day’s conversation floated into a word cloud above our heads, “community,” “belonging,” “great energy” and “momentum” emerged as the clear favorites.

Vallejo resident Karen Sims spoke of the range of community-based initiatives, saying the artistic opportunities in the city give people “vibrancy and hope.” Erin Bakke, artist and founder of Vallejo Art Windows, a project that puts local artists’ installations in vacant storefronts, said, “You can feel it, there’s a vibe… it’s very energizing.”

The superlatives themselves gained momentum. Chris Viridian, one of the Hub’s co-founders, moved to Vallejo after the city filed for bankruptcy. At the time, his monthly mortgage cost less than what he had been paying in rent elsewhere. “A lot of artists moved in because it was cheap,” he said. “Right now, what we have is very reminiscent of what we had in Paris in the 1930s,” he said. “It is always the artists that turn the communities around.”

The Rottners touched on this very subject earlier in the day, but with a hint more caution: “I think the issue is, you make Vallejo better, but you don’t want to change its essential nature. Part of what’s great about it is how it is now,” said Andy. “I think that’s something a lot of places in the Bay Area are facing. How do you improve things?”

The Hub and people gathered within it seem to focus their energies on the downtown area, in a grassroots form of creative placemaking. The second Friday of every month, the Vallejo Art Walk brings artists, food vendors, musicians and locals to the downtown blocks, joining forces with 31 nearby businesses. Across the street from the Hub, the folks at Artiszen — not to be confused with having anything to do with Zen Buddhism — talked to us about their planned summer arts classes for Vallejo children. The city’s annual Mad Hatter Holiday Festival gathers flame-spouting art cars, the local California Maritime Academy’s marching band and (this year) Storm Troopers in a parade down Georgia Street, ending with a tree-lighting festival.

Such gathering spots and events, instituted by a local arts community of mostly transplants, have entwined themselves in the very fabric of the city. But in the push to revitalize downtown Vallejo through the arts scene, is there still room for projects that don’t produce objects or fit under the umbrella of “community arts”? What does it mean to live in Vallejo if you don’t make large-scale Burning Man sculptures, steampunk accoutrements or window displays?

As we left the Hub, we set out to answer that very question.

Reverb with Re:Sound

After a hurried but delicious lunch at Gracie’s BBQ, we journeyed across the Napa River to Mare Island. The Mare Island Naval Shipyard, a major element of the city’s economic engine throughout its history, closed in 1996, leaving behind rusting equipment, acres of empty buildings and the loss of 5,800 jobs. Today the strip of land is home to (among others) Touro University, a golf club, a prefabricated home company and the Mare Island Shoreline Heritage Preserve, aka the location of an experimental sound concert series called Re:Sound.

Sound artist and special education teacher Jen Boyd greeted us at what looked like the end of Railroad Avenue, unlocking a chain-link gate to lead us deeper into the preserve, fennel surrounding us pungently on all sides.

Re:Sound is just one year old, but Boyd says the response has been extremely positive. Her two- to five-hour-long concerts bring sound artist luminaries into a cavernous concrete building formerly used by the Navy to store munitions. “Everyone I bring here is like, ‘I didn’t know this existed,’” she says.

Her voice echoes for what feels like forever — the building creates a six-second tail of reverberation. “When artists play here, their pieces are driven by the space,” she says. Each concert draws an audience of about 120 people from all over Northern California to what Boyd likes to a call “a forgotten space.”

For Boyd, who relocated from Oakland to buy a home in Vallejo in 2010, Re:Sound is a labor of love. She provides the generators, porta-potties and promotional materials for each concert, and helps the performers out as much as possible with travel costs. “I wanted to bring something to Vallejo,” she says. “I play a lot in San Francisco and Los Angeles and I just wanted to bring something here.”

The next Re:Sound concert will be a two-day affair on Feb. 20 and 21, scheduled to coincide with the San Francisco Bay Flyway Festival, a celebration of aviary wildlife at the peak of their migration. Distancing herself from certain activities at the Hub (fire-breathing sculpture, for one), she underlines the importance of listening to nature — in both the Re:Sound concerts and her own work.

Does Boyd, like everyone else we met, think we, too, should move to Vallejo? Yes, but with a caveat: “I think people should come so we can start more diverse stuff.”

What We Didn’t See

It was time to leave the “Up-Bay.” (We don’t know if this is a real thing that people say, we only heard it once.) But surrounded by eight-foot-tall fennel plants, the car wouldn’t start. Would we be trapped on Mare Island forever? Would that be so bad?

Partly due to our prolonged stay at the Hub, and partly due to our own underestimation of what Vallejo had to offer, we ran out of time to accomplish our day trip’s lofty goals. We didn’t see the restored interior of the Empress Theatre, a 471-seat music and performance venue downtown. We didn’t have time to visit the Coal Shed Studios on Mare Island, where 18 artists pursue their practices. We did meet Henry Beecher, chair of the McCune Rare Book and Art Collection, but we couldn’t browse the collection itself. We ate BBQ chicken, but we didn’t sample any recommended taco trucks. We didn’t even catch a glimpse of the ferry to San Francisco, let alone sample the Mare Island Brewing Company’s Taproom.

The car finally started and we began our reverse commute back to the East Bay. With rental rates in the Bay Area showing no sign of decline, perhaps Vallejo is the burgeoning art community you’re looking for. We barely scratched the surface. And Zillow’s looking good, at least to Lakshmi.