Imagine you’re in preschool. Crayolas are your jam. You’re coloring up a storm. You reach for the black crayon to add some dark squiggles to your abstract expressionist masterpiece, and this other kid takes it away. You look for another black crayon. Again, taken away. In fact, every single black crayon in the entire preschool — nay, the entire world — is in the clutches of this one kid. And you can’t use any of them.

‘Why?’ you ask. ‘Why can’t I use the black?’

Because, I say: Anish Kapoor.

Sir Anish Kapoor, the Indian-born British artist responsible for Chicago’s Cloud Gate (a.k.a. “the bean”) has long worked to mine the emotional and psychological effects of color, surface and depth. His sculptures made from polished stainless steel twist and distort reality; objects coated with raw pigment seem to flatten to pure color.

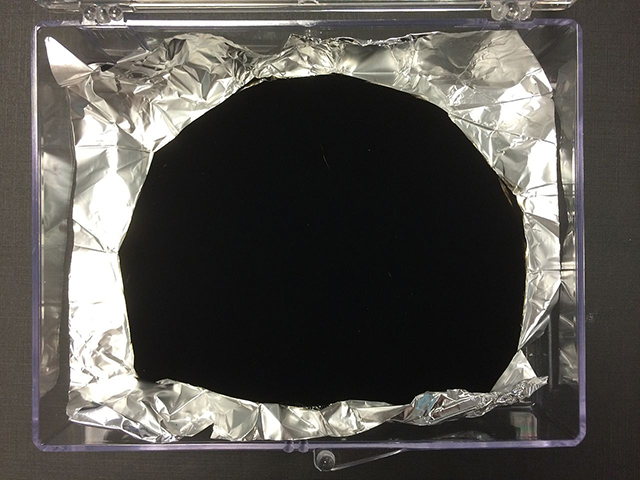

In 2014, Kapoor began working with Vantablack, a new product developed by the British company Surrey NanoSystems. The carbon nanotube material was dubbed “the blackest of blacks,” and is, according to the Guinness Book of World Records, the world’s darkest man-made substance.

Awesome, the world said. Anish Kapoor will do amazing, great and probably beautiful things with this material we can’t even afford to understand.

But then the Surrey NanoSystems website announced all future artistic applications of Vantablack would be reserved exclusively for Anish Kapoor, stating: “We have… chosen to license Vantablack S-VIS [the spray-on version] exclusively to Kapoor Studios UK to explore its use in works of art. This exclusive licence limits the coating’s use in the field of art, but does not extend to any other sectors.”

Artists everywhere were peeved, including those in the Bay Area. “It sounds like a gimmick to me,” says artist Julia Goodman, who makes low-relief handmade paper sculptures and works with beets.

“I understand why it’s an appropriate material for Anish Kapoor to use,” says Oakland-based artist Torreya Cummings. “But it’s the part where he won’t let others use it that’s weird.”

“It’s like, dude,” sculptor Tamra Seal says, “share the goods.”

Granted, Vantablack is likely out of reach to most earthly denizens even without Kapoor accepting exclusive rights. On NanoSystems’ FAQ page, the question of “Can I apply Vantablack to my car?” (obviously the first thing on my mind) is answered with, “Though this would undoubtedly result in an amazing looking motor… this [is] an impractical proposition for most people. It would also be incredibly expensive.”

But now we can’t even dream of turning our cars into Batmobiles in the name of art. “I had no designs to ever use it,” says artist Nando Alavarez-Perez, “but then it was like f— you, you a–hole.”

Other artists have developed secret studio methods and invented new materials (International Klein Blue comes to mind), but they did it on their own, through the sweat and labor of their studio practices.

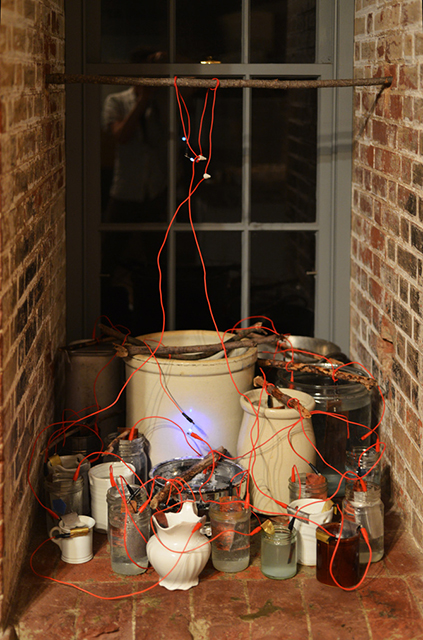

Secrets can be useful tools for artists, Seal says. In a recent group show at Oakland’s City Limits, her sculpture Halo was made of “plastic, paint and secret ingredient.” Knowing exactly how something was made and what it was made out of sometimes demystifies a work, she thinks. “Now they have to scratch their head and contemplate it. How did she make this?”

But for Kapoor and his Vantablack, the issue isn’t a pleasant conundrum so much as a nagging reminder of the obscene wealth (and ego) of the art-world elite.

“The idea of owning something he didn’t invent himself feels really wrong to me,” says Goodman. “I’m building on such a long history of making rag paper. To try to truncate and isolate myself from that feels like a disservice to the work and the community of artist papermakers I work in.”

As the blog Who Wore It Better clearly shows, artwork doppelgängers constantly manifest. “Things are in the air,” says Cummings. “Art is reflecting consciousness and experience and reality, there are going to be things that overlap and coincide.”

Is Kapoor so insecure about competition that he needs to corner the market on Vantablack? “It would be great if I was the only artist allowed to use extruded aluminum,” Alvarez-Perez jokes. “But even when I say that it sounds so insane!”

Would any of the artists surveyed for this article like to claim a particular material for their own exclusive use? Not a one. “I do love my materials, it’s true,” says Goodman. “But I don’t want to own my materials. I think work is best when it’s in conversation and not isolated.”

If anything, Seal says, she would want to invent a new material of her own, Yves Klein-style.

These Bay Area artists are just too darn nice to spout ill will. So I’ll do it for them. If NanoSystems’ other collaboration is any indicator of what the future holds, Kapoor’s exclusive rights will culminate in an artwork resembling this inane Vantablack-coated container of Lynx deodorant body spray: