In January 2016, Oakland’s City Limits held a one-night-only exhibition of new works by several artists, including Bay Area Painting Right Now alumna Lana Williams. It was a terrific show; I hope you saw it! But while several pieces stayed on my mind over the following days, the one I still can’t get over is Sam Spano’s In The Realm Of The Senses.

In The Realm Of The Senses is a sculpture of a dog in lotus pose sitting on a black platform on top of a decorative rug. The dog’s eyes are closed tightly; it assumes the serene concentration befitting its quest for peace. And yet, in Spano’s installation, the dog meditates in front of a mirror. Does the dog’s focus stray so it can sneak a peek? Does it admire its own transcendental bliss in action?

Spano purchased the figure online and painted on its surface. The rug and the mirror imbue the dog with a certain glamor, a kind of splendid Cali narcissism we hardly ever associate with loyal, cuddly canines.

In The Realm Of the Senses is funny, of course. But it also cues key themes pervasive in Spano’s work: pleasure, the domestic, and the coincidence of the two.

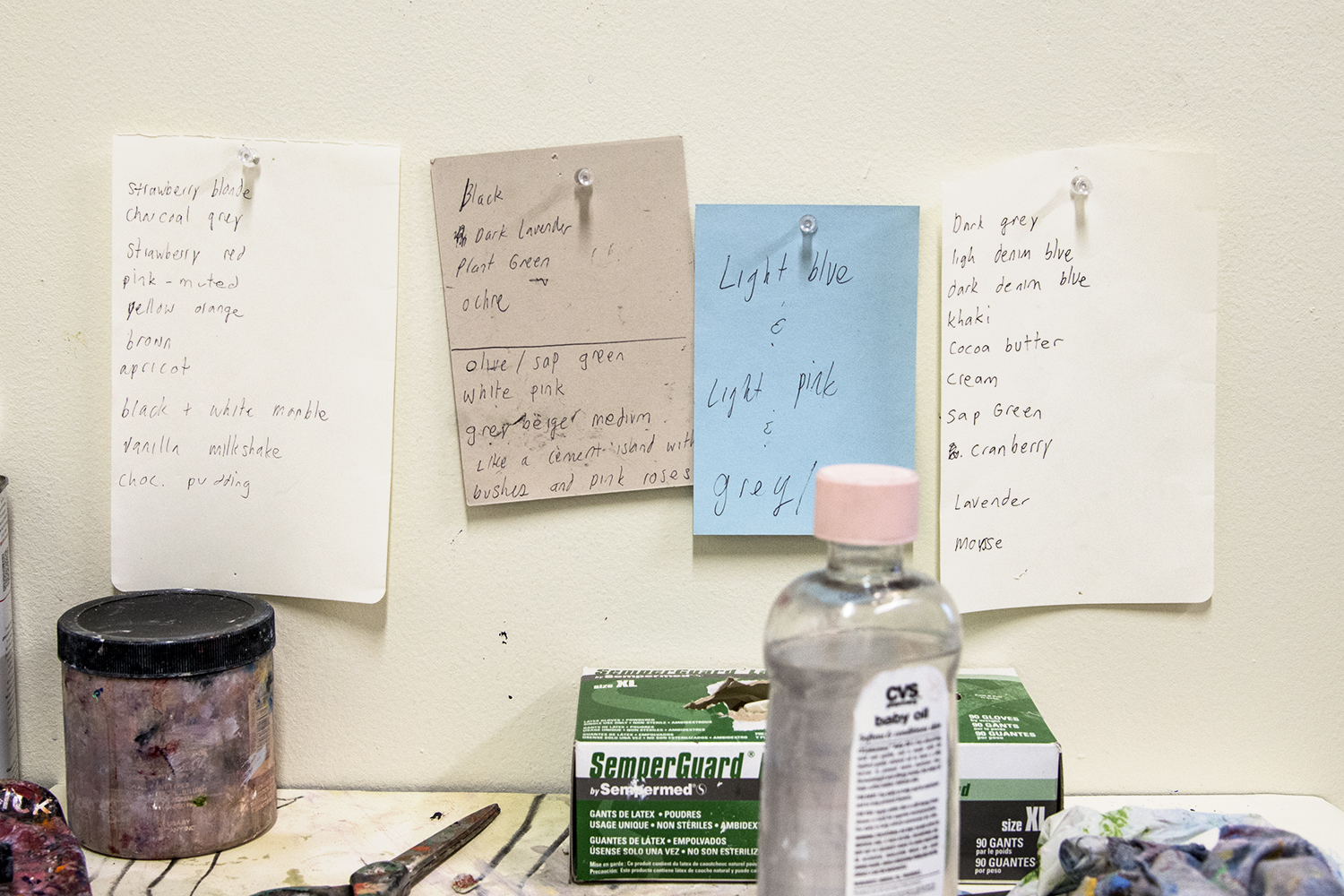

The pleasure of the interior, which of course includes meals and snacks, is a fundamental influence on every element of his painting, starting with color. Spano’s paints and brushes lie on a small table in his studio. Above it, on the wall, are three list poems, descending nouns with stray adjectives. Each phrase corresponds to an idea of color. And it’s true, each is an inimitable visual experience.

Take “chocolate pudding” for instance. Yes, it’s dark brown. But it’s also sui generis, chocolate pudding unto itself — more a jiggly feeling than a fact of light. This is the conceptual apparatus underlying Spano’s canvasses.

Most of the conceptual colors on these lists are edible or potable. Spano’s association of color with comestibles underscores his work’s grounding in domestic themes. But it’s not just the sensible and gustatory memory of food and drink behind his feel for color. His work insistently takes place indoors, in the places where we purr and rest, feed and play. In the places where we are — theoretically — the least mediated and the most ourselves.

For a new series, Spano conceptualized and documented a domestic interior with his friend Katie Burge. The scenes took place in her home, where she pursued an ordinary afternoon: lounging in her robe, using an exfoliating facial mask, smoking weed out of a bong.

Nothing is especially extraordinary about these scenes — except, perhaps, that Spano and Burge buck the traditional gender dynamic that usually characterizes such a scenario. Instead of ‘directing’ Burge, Spano followed her lead. Her decisions, her movements, her ideas were the source material for the work to come. While Burge went about her afternoon, Spano took hundreds of photographs, seeds for the vast array of artworks this afternoon would inspire.

Spano’s works take a number of forms, from abstract and figurative paintings to breathtaking charcoal drawings. The paintings themselves are of wildly different styles and approached. Burge’s robe, with its ornamentation against solid color, becomes the departure point for abstract renderings of color and shape. Another painting, showing Burge exhaling a sweet cubic gallon of marijuana smoke, gives Spano the opportunity to luxuriously spread dense puffs of white rhythmically around the canvas (is “weed smoke” a good candidate for Spano’s list poem?).

We discuss the future paintings in the series, and Spano describes with relish his plans for an oil painting of Burge in a sticky facial mask, savoring the textures to come.

Looking at dozens of drawings, watercolors and oil paintings, all showing Burge in her domestic space, recalls a long and fraught history of men representing women alone in their personal spaces. Spano is aware of this history, which has historically sublimated, indeed helped create, the powerful and violent “male gaze.”

But while his project obviously recalls and cites centuries of such problematic scenes in western paintings, the approach and specifics of his representation feel different, if obviously not fully redemptive, by virtue of his thoughtfulness and care. The series reads to me more like a tribute to Sam and Katie’s friendship than the hard gaze of an auteur representing the female body for mere consumption.

The humor in Spano’s work treads a very fine line between irony and earnest delight. I mean, of course In The Realm Of The Senses is funny. And yet in conversation, another dimension appears.

Spano describes a long period during which he repeatedly painted wolves. The wolf, he realized eventually, represented his own feelings. In his own painful and difficult time, the wolf was both fear and ferocity. This wolf, he tells me, gradually turned into the wolf’s famously mellow cousin: the dog.

If In The Realm Of the Senses produces an ironic distance that even we Californians need in order to recognize our own beauty and silliness, it also hearkens to Sam Spano’s increasing okayness in the world. In some way it stands in as a sublime emblem of everything chill, everything delicious.