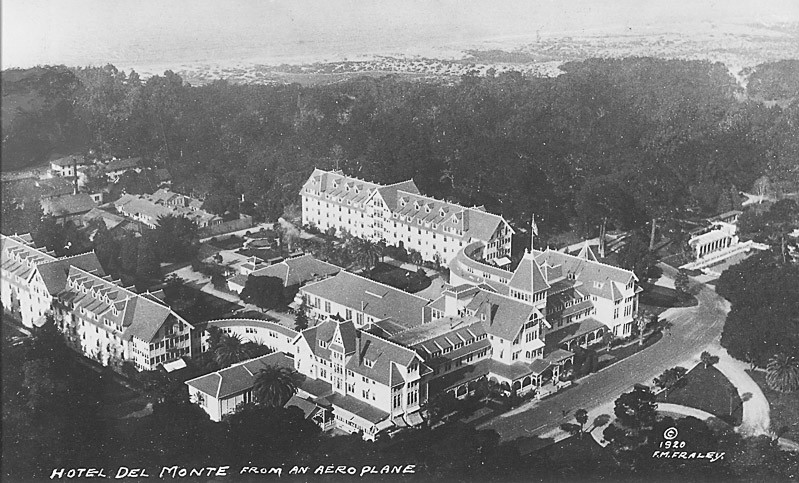

The Museum of Monterey is about to become home to the largest collection of works by Salvador Dalí on the West Coast. Does that sound bizarre? What connection, you ask, does the Spanish Surrealist painter have to this coastal city famous for sardines, fancy cars, and jazz? Quite a big one: Dalí spent his summers at Monterey’s Hotel Del Monte over seven years in the 1940s, when he wasn’t shuttling back and forth between New York and Hollywood.

“There is a real significant connection between Monterey and Salvador Dalí,” says Marc Del Piero, a longtime board member for the Monterey History and Art Association, which among other things, runs a museum at the foot of Fisherman’s Wharf.

Del Piero says public interest in things like its extensive maritime collection has been fading for years. “If what you’re selling no one wants to buy, you either need to change what you’re selling or plan on going out of business. And we’ve been around for nine decades. We’re not going out of business.”

“We knew we had to do something new and innovative,” association president Larry Chavez added. “Something that would grab tourists.”

Highlighting local history is part of the organization’s mission, so when the board put out a request for proposals to remake the museum, they were taken with a pitch put forward by a Pebble Beach resident. Russian-born real estate investor Dmitry Piterman has a massive collection of work from Salvador Dalí — perhaps his personal passion could dovetail neatly with the museum’s institutional needs?

Piterman has been obsessed with Dalí since he was a college student at UC Berkeley. On a date one night, he wandered into a San Francisco art gallery and encountered the Dalí oil painting “Soft Construction with Boiled Beans.”

That painting anticipates the onset of the Spanish Civil War. Disjointed body parts clutch each other in a desperate wrestling match against a cloudy Catalonian sky. Dalí himself described it as “monstrous excrescences of arms and legs tearing at one another in a delirium of auto-strangulation.”

“It almost was borderline grotesque,” Piterman recalls. “The styling and the craftsmanship was really amazing, and it kinda make you stop and think. You know? What is he trying to say?”

The college student didn’t have money then, but Piterman began to study Dalí. He vacationed in Spain, and visited Figueres, Dalí’s birthplace and home to the foremost museum of his work. As he did make money, Piterman moved to Spain and started to collect artwork. He collected everything he could get his hands on, but found the paintings expensive and often unattainable, locked up in museums and private collections.

But Dalí was prolific. He left a wealth of etchings, lithographs, sculptures and tapestries. There are more than 540 items in Piterman’s collection, and he’s not done yet. It’s the largest collection in the US outside of the Salvador Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida.

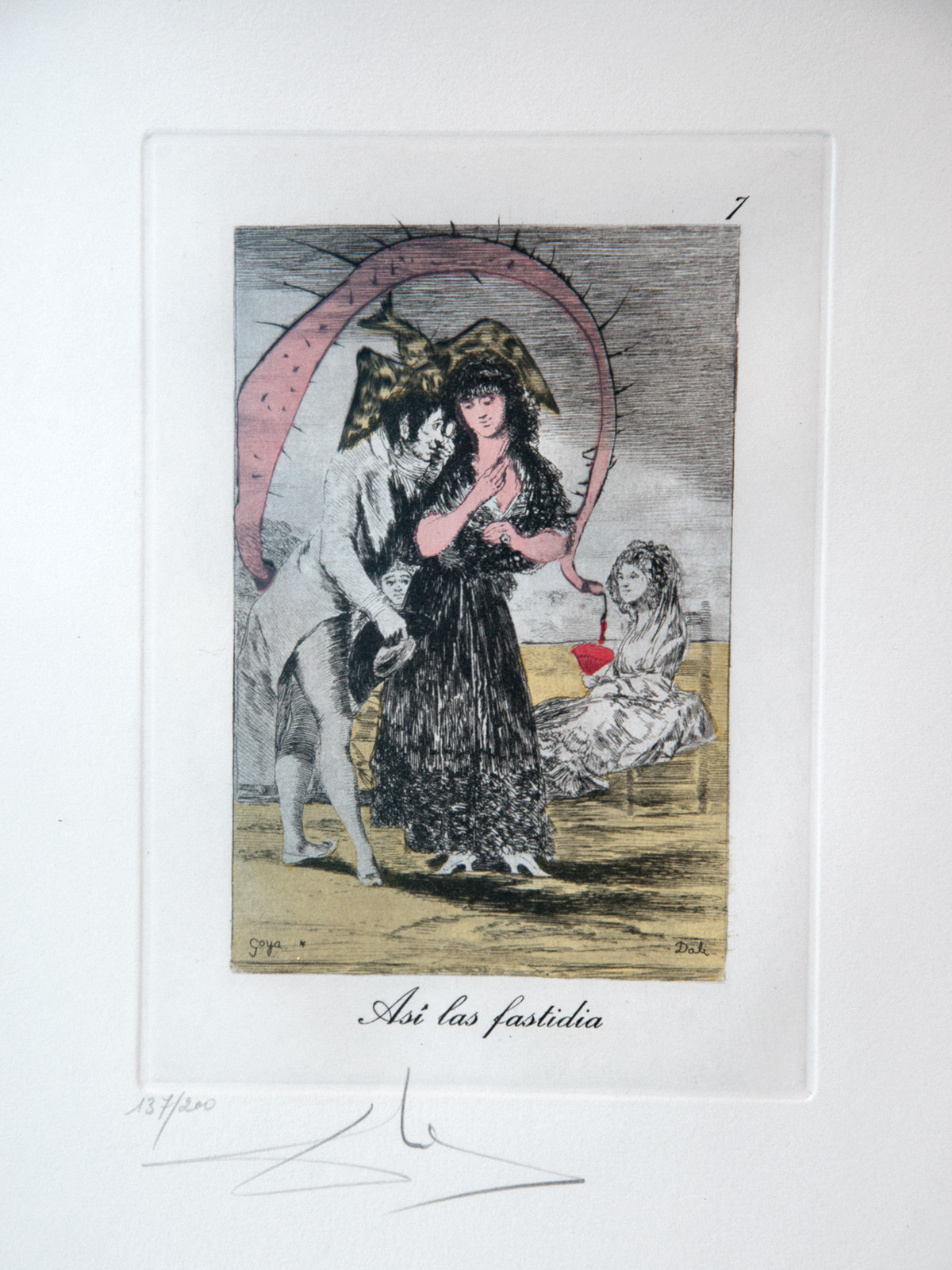

By Piterman’s own estimation, collection highlights include a print of Dalí’s most famous painting, The Persistence of Memory, as well as a provocative series of reworkings of Goya. “It’s not really plagiarism,” says Piterman. “He modified them and made them Dalínian. Some of it is comical. Some of it is serious.”

Piterman says the most compelling aspect of his collection for him is its breadth. “You can see a significant change,” he explains, over the course of Dalí’s lifetime. “A radical and a rebel in the 1930s and 40s, Dalí became religious at the end. He also improved his craftsmanship. His attention to detail became more and more precise.”

Following Piterman’s return to the US from Spain in 2007, he talked with people at UC Berkeley about housing some of his growing collection. But he found at the Museum of Monterey he could take over the whole building and even rename it.

The old collection isn’t being decommissioned; just farmed out to places like the San Francisco Maritime Museum. This leaves the Museum of Monterey open to a complete remodel, financed by Piterman. There will be new paint, lighting, and flooring, but also a new concept to tie the building together.

Piterman is still in preliminary meetings with contractors and artisans to come up with something befitting Dalí. “He was a provocateur: thinking outside the box, painting outside the box.” Piterman adds, “Every museum that houses Dalí work has kind of special look to it, from outside as well as inside.”

Piterman is particularly excited about the museum’s built-in theater. He anticipates a rotating playlist of documentaries and clips from the movies Dalí helped make. Dalí loved American pop culture. He worked for Walt Disney and Alfred Hitchcock. Among other things, Dalí designed the dream sequence in Alfred Hitchcock’s “Spellbound.”

Dalí was also a regular on TV talk shows, including a visit to the Merv Griffin Show in 1965. For those who don’t want to watch the whole thing, let me excerpt a fun exchange.

Dalí: My work consists in the meticulous execution of my dreams.

Griffin: You dream your paintings.

Dalí: Dalí dream in glorious technicolor!

Dalí’s penchant for showmanship, starting with his trademark curly cue mustache, makes it easy to dismiss just how radical many of his ideas were when first introduced. “Surrealism certainly influenced the emergency of abstract expressionism,” says Lila Staples Thorsen, an associate professor of art history at Cal State Monterey Bay. “Rothko. Rauchenberg. So many of our mid-century greats were directly influenced by Dalí.”

Monterey, not so much. Though it celebrates many cultural luminaries from its past — John Steinbeck, Ed Ricketts, and Robert Louis Stevenson — Monterey has not claimed Dalí as one of its own.

Yet.

“This is a vibrant community in terms of art and culture,” Thorsen says. “For a fairly small area, we’ve got a terrific history, and a crowd of visitors and a crowd of residents that support the arts and are interested in the arts. So I think he [Piterman] could really make a go of it.”

It doesn’t hurt that Dadaism, a kissing cousin of Surrealism, is celebrating its 100th anniversary, something that will generate events and press coverage this year, sparking a resurgence of public awareness for both movements.

Already, Dalí collectors are contacting Piterman and the Monterey History and Art Association to talk about loaning out pieces to the remade museum. Pieterman says he hopes to expand his collection, too, possibly with works that feature California subjects like Dalí’s 1970 series of the Golden Gate Bridge. If all goes smoothly, the museum in its new incarnation is expected to open in May, right around the anniversary of Dalí’s birthday on May 11.