Berkeley-based photographer Katy Grannan’s first foray into filmmaking focuses on Kiki, a charming but deeply troubled drifter who lives in the ravaged community of Modesto’s South Ninth Street. Five years in the making, THE NINE builds on Grannan’s photographic series Boulevard, The Nine, and The Ninety Nine, quiet elegies to those living on the ragged edges of society.

KQED Arts caught up with Grannan, who will speak about her work in a round of Pop-Up Magazine appearances at venues in Brooklyn, Los Angeles, San Francisco (sold out), and Oakland (tickets still available) this month. And for those with frequent flyer miles to burn, THE NINE debuts April 20 at Visions du Réel in Switzerland.

What motivated you to explore this subject in a film context? What made that the next creative choice?

I’ve been making photographs for a long time, and the photographs function on many levels. What they can’t do is convey context of the conversations, exchanges, experiences, and energy of what was often meeting someone for the first time. I want the photographs and the film to live on their own.

The film had been in the back of my mind for a while, and I was feeling like I need to do something new and to challenge myself. I kept revisiting this one neighborhood in Modesto, one that is its own contained universe despite being just a few short blocks. It’s basically where people go to check out. The more time I spent there, and the more I got to know people living there, it felt like a situation and space I wanted to know better.

You’ve committed considerable time to these photographic and cinematic projects, and in the process seen much of California’s interior and those who live there. Could you describe the process of getting to know the population you’ve worked with?

As a bit of context, I photographed a woman for many years and when she disappeared, I started looking for her. The series started with me searching for her in the Mission and the Tenderloin, in SROs and alleys. I started photographing people along the way, people who are otherwise completely ignored. Previously, I put ads in the paper and met people through that, and it was uncomfortable.

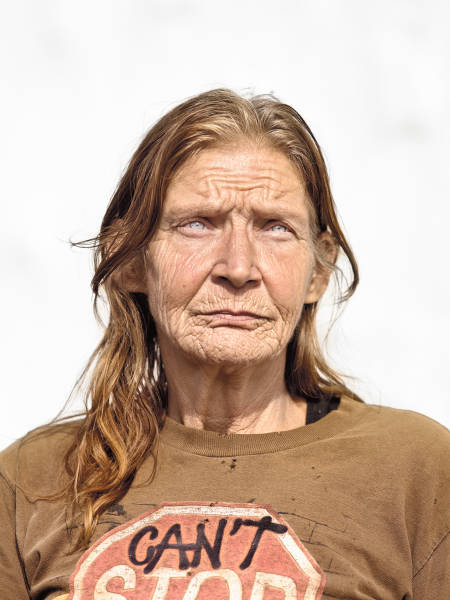

This way, approaching people on the street, seemed to be a reasonable midpoint. The whole process turned into a street studio of sorts. We’d look for a white wall, something on the fly and very simple, amidst a busy city. I found that it required someone, as subject, to be generous or not embarrassed to go through the process with me. I met several people like that, and I think part of that willingness comes from feeling ignored otherwise.

Over time, the people I got to know on the Nine, which is local speak for that block of South Ninth Street in Modesto, got to know me and a few details about my past including a cousin and childhood friend who both succumbed to drug use. They recognized me as someone who wasn’t interested in exploiting their misery for personal or aesthetic gain, but rather someone who wanted to get close to a reality that, on the whole, our society doesn’t want to acknowledge.

We’d rather not think of ourselves as capable of making the kinds of mistakes that lead to living in conditions or a place like the Nine. I wasn’t interested in depicting prostitution or drug abuse or the ever-present violence. We’ve seen those movies and know those stories, and over time, we disconnect. I wanted to portray what life is like most of the time, which involves conversations about ambition, hope and regret.

You worked with your studio manager, photographer and assistant director Hannah Hughes. That’s two people who, as you described, started from scratch as filmmakers. Can you describe that experience?

Up until very recently, you’re right, we were a two-woman crew. I can’t stand working with too many people because it draws my focus away from whom I’m interacting with. Also, to bring a big crew into a space like the Nine would be disrespectful, and it sends all the wrong message about our motivation. In truth, we made every amateur hour mistake. Of course, we know how to make pictures, but approaching a scene with a photographer’s sensibility as far as framing and content and interjecting into the scene was just wrong. As Hannah said recently, we just went through the equivalent of five years of film school. From that perspective, I’m looking forward to photographing again, but I’m also excited to make another film based on all that we’ve learned from this experience.

What are your thoughts on the Pop-Up Magazine events? You’ll be speaking to an audience that, by best guess, has never experienced the raw end of life exemplified by those you got to know on the Nine. Do you want to narrow that experiential gap?

This is a first for me. I’ve only heard about Pop-Up Magazine and how much people love the events. I’m actually really nervous about being a big bummer. There will be all these witty writers and people who are accustomed to storytelling, and I’ll be the one who drags it all down. But, I think that people respond to candor, to authenticity, to talking about experiences. I created something especially for Pop-Up that involves photography and some conversation clips about the film. But it’s also about our experience, it’s personalized, and I hope that people understand the shared humanity that’s captured in the film.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.