One of the largest map collections in the country is about to open at Stanford. The David Rumsey Map Center is not just big in size, with more than 150,000 items, including rare first editions. It’s also accessible world-wide because many of the maps have been digitized; more than 67,000 items.

Retired real estate developer David Rumsey has been obsessed with maps since he was a small boy, and he’s been collecting for more than three decades. “I like modern maps, I like old maps,” Rumsey says. “I just find them fascinating. They’re art. They’re science. They’re history. All of those things.”

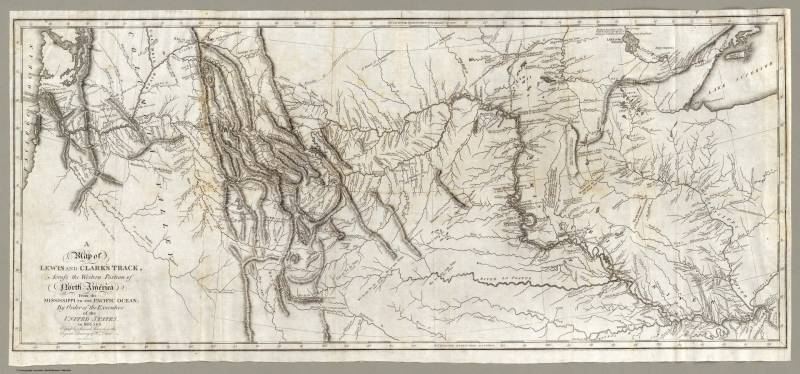

Rumsey has donated his entire collection to Stanford. It includes atlases, wall maps, globes, maritime charts, and even children’s maps made for school assignments. Highlights include a 19th century Jain cosmological diagram hand-painted on cloth, a leather-bound book considered to be the first true world atlas, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (1570), and a map from the first published edition of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark’s Account of the Expedition.

Other map collections are represented at the center, including Glen McLaughlin’s California as an Island, which tells the story of a long-cherished misconception about California held by European map makers when the New World was still largely terra incognita to them.

Rumsey says he picked Stanford over other potential libraries because he didn’t want his maps locked away in dusty archives. “In the past, these kinds of collections were more about preservation, which is good, very admirable,” Rumsey says. “But we would like to change that paradigm.”

Digital revolution makes collections more accessible

A growing number of major map repositories have signed onto what’s known as the International Image Interoperability Framework. It’s a system that enables participating institutions to share their collections using compatible software to deliver high resolution images to anyone who asks. As a result of this development, curators everywhere can more easily put together exhibitions without having to physically bring artifacts to their museums. “It doesn’t matter where the actual image is,” says G. Salim Mohammed, the curator who heads the David Rumsey Map Center. “It could be in Europe. It could be in Africa. It could be anywhere there is Internet access.”

In addition to curators, the system stands to benefit scholars, school children, environmentalists, artists, and other groups.

“Maps in physical form are beautiful, but they’re hard to work with,” says Rumsey. “In digital form, they’re light as a feather.”

That Said, You Really Should Visit Stanford

So why go to Green Library, the physical building where the Center is located? For one thing, you’ll want to see the inaugural exhibition, A Universe of Maps in the Peterson Gallery on the library’s second floor. Massive printouts of the digitized maps from the collection are on the walls, including in the rotunda and in the stairwells. They’re even etched onto the glass doors at the entrance of the center. The sharpness of the detail is stunning. It may take you an hour to make your way into the center itself.

Once there, two floor-to-ceiling computer screens immediately capture your attention. One is a 12 x 7′ touch screen, for those big and small who’ve learned to relate to visual images through an iPad. The other screen is 16 x 9′. “These are basically a screen savers that we commissioned from Stamen Design in San Francisco,” Rumsey jokes, just before he shows what you can do with them.

It’s not that you can’t zoom in and out, cross fade between maps, and do side-by-side comparisons on your laptop at home. But on a giant screen, you can zoom in to see incredible detail that often goes completely unnoticed when you’re looking at a map as a whole.

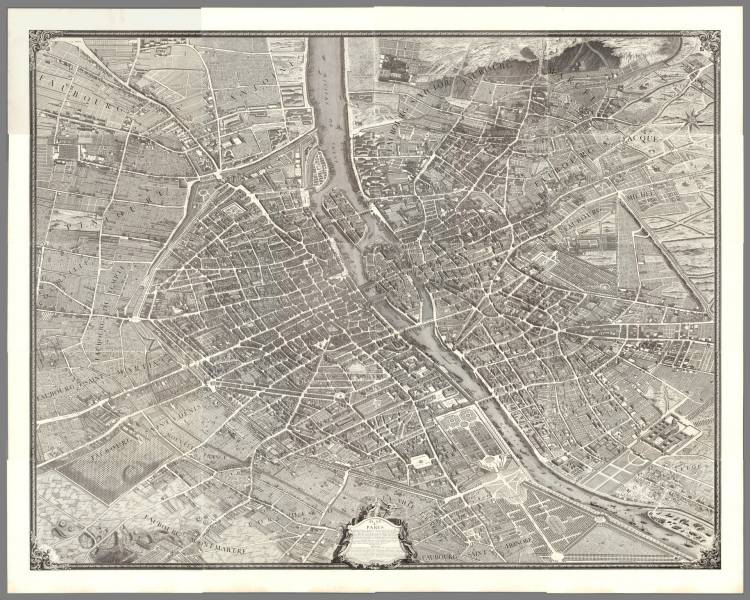

Rumsey pulls up Plan de Turgot, a map of Paris from 1739. “It’s 20 sheets in a book, but we knitted them altogether into one gigantic image,” Rumsey says. On Rumsey’s big screen, you can see a huge amount of detail. “You see all the piles of wood?” Rumsey says. “That’s the heating source for Paris in 1739.” Rumsey clicks around, to show how wood is making its way from outside the city to homes inside. “The man that made this map had permission from the king to go into all the back yards,” Rumsey says. “So he has the gardens. It’s just an extraordinary cultural record. Maps are just like books. They’re filled with all kinds of stories to tell.”

The David Rumsey Map Center opens for special events Tuesday, Apr. 19. It opens to the public Tuesday, Apr. 25. More info here.