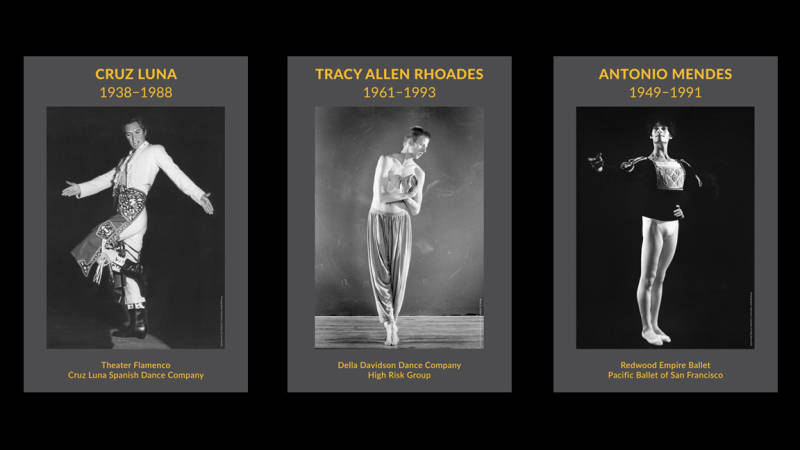

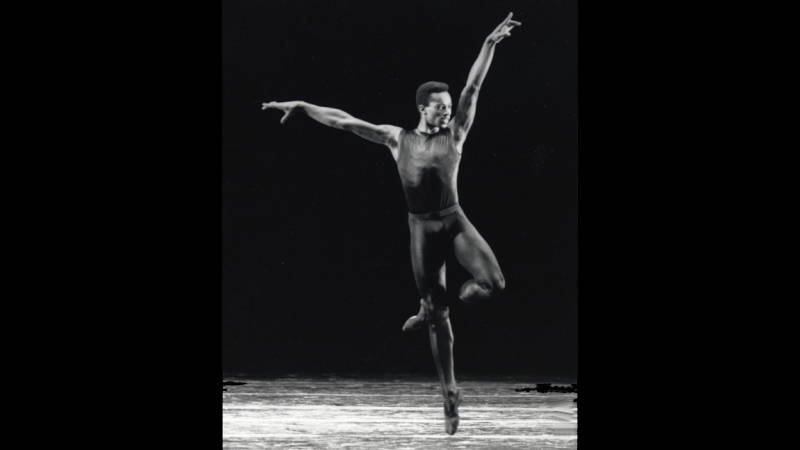

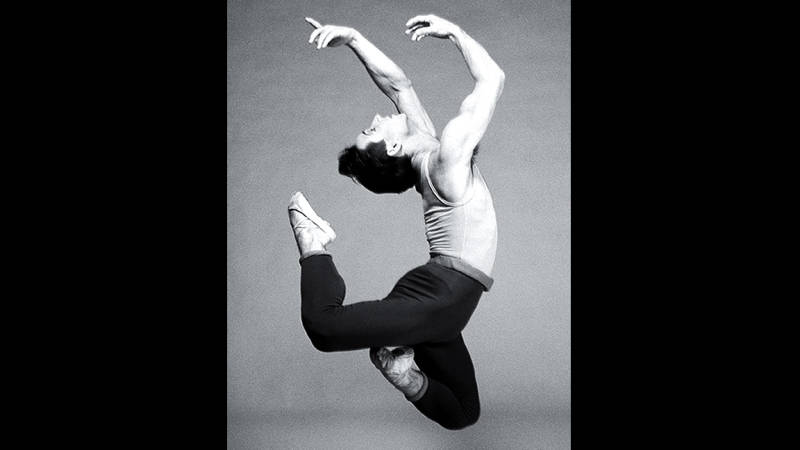

A new exhibition of photographs housed at the Community Gallery at the GLBT History Museum in San Francisco’s Castro neighborhood gathers together a series of portraits of Bay Area dancers who died during the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s and 90s. The images in Dancers We Lost: Honoring Performers Lost to HIV/AIDS capture the dancers at the height of their powers. Their physiques are toned and enviable. They strike graceful, impassioned poses – some mid-air — in tights and in costume.

The photographs, all mounted on black paper, indicate the dancer’s name, his Bay Area dance company, and the years of each performer’s birth and death. Russell Hartley (1926-1983), who also worked as a costumer for the San Francisco Ballet, appears in the Mother Ginger outfit he designed for the first U.S. production of The Nutcracker, which was staged in 1944 at the War Memorial Opera House. A necklace hangs down on Alvin Ailey’s bare chest (1931-1989) as his arms arch upward. Charles Ward (1952-1986) leaps to his right, his arms and legs aimed like arrows at a distant bullseye.

Until McElhinney started work on this project, these dancers and their contributions to arts in the Bay Area seemed poised to disappear from the history books. “Absence is the word that came to mind when I began to research these performers,” says the show’s curator Glenne McElhinney in her exhibition notes.

The exhibition originated with McElhinney’s research on the legendary, San Francisco-based dancer and choreographer Zack Thompson, who had a dance studio on the second floor of the Black Community Center — housed at 330 Grove Street from 1968 to the mid-1970s — and died of AIDS at the age of 61 in 1996. “People kept telling me, ‘He was crazy; he was wild; he was an amazing dancer,’” McElhinney says of Thompson. “This came from so many different voices. They would say, ‘We don’t know what happened to him, but he would be a great interview.’” Once she turned her full attention to Thompson, McElhinney fell in love with his story.

Thompson became internationally famous as a black jazz dancer, danced with Katherine Dunham and Josephine Baker, and lived for many years in Toronto, Paris and Amsterdam before returning to the Bay Area, where he had grown up. Although McElhinney knew little about dance before starting the project, the roll call of dancers who died too soon quickly took hold of her imagination. “I started researching his contemporaries so I could interview them and I found they were all dead,” McElhinney says. “Then I researched their contemporaries and their dance colleagues and they were all dead.”

McElhinney also contacted many of the dancers’ families who had saved years of ephemera. She has manila envelopes stuffed with old photographs, playbills and programs relating to performers featured in the exhibition. Over the next few years, the trove of photographs, scrapbooks, personal papers, biography files and items will go to the Museum of Performance + Design in San Francisco. And, as a result of her findings, the curator is now in the process of producing a short biographical film about Thompson and his life as a dancer.

The memorabilia clearly shows how the performers’ families still take pride in their son’s or brother’s achievements, and underscores how much they were deeply loved — and are still deeply missed.

Dancers We Lost: Honoring Performers Lost to HIV/AIDS is on view at the GLBT History Museum through Sunday, Aug. 7.