Opening the door to The Grace Jones Project at the Museum of the Africa Diaspora is like entering the shrine of a living goddess.

In the center of the gallery two display walls separate the space, drawing a line through the exhibit. On one side of the line, the artist represented is Jones herself. Thirty-two evenly arranged Grace Jones records are divided and mounted on black backgrounds. The singer, actress and model features prominently on almost every album cover. Her aura, and her shifting series of identities, dominate the room. The effect is that of a pop star’s power to dazzle.

In the center of the gallery two display walls separate the space, drawing a line through the exhibit. On one side of the line, the artist represented is Jones herself. Thirty-two evenly arranged Grace Jones records are divided and mounted on black backgrounds. The singer, actress and model features prominently on almost every album cover. Her aura, and her shifting series of identities, dominate the room. The effect is that of a pop star’s power to dazzle.

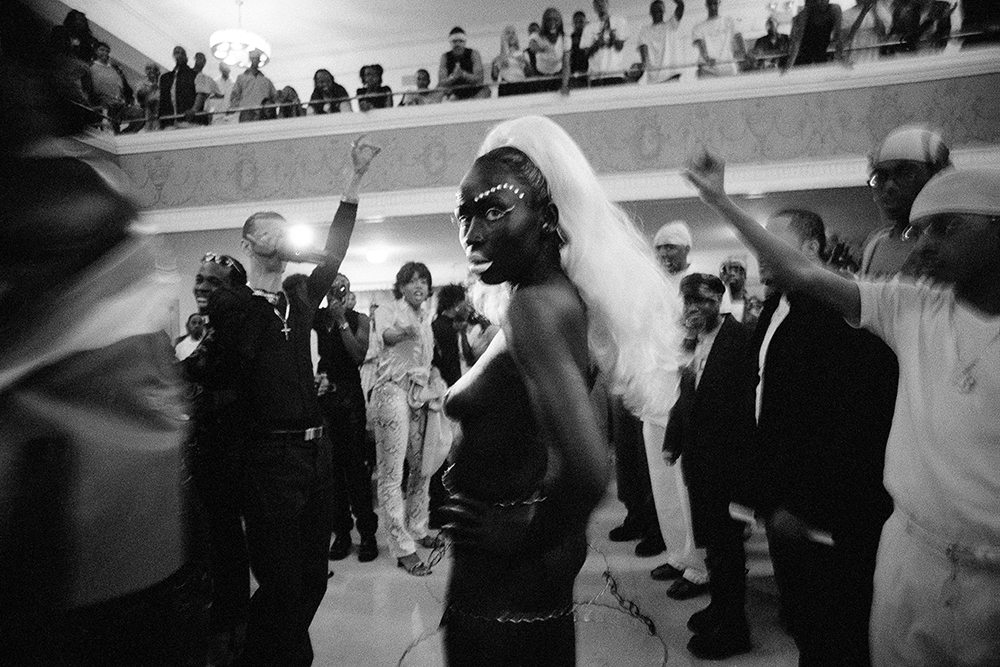

A reel of Jones’ music videos loops alongside the wall of albums. The projected images shriek with the 1980s MTV era of self-conscious experimentalism. Jones and her collaborators capitalized on the fact that the camera loved to look at her. But she knew how to look back. Jones stared down the male gaze and smashed it to bits. Sunglasses, costumes, hats, cowls, even her makeup were all parts of the armory, to be removed only at her behest.

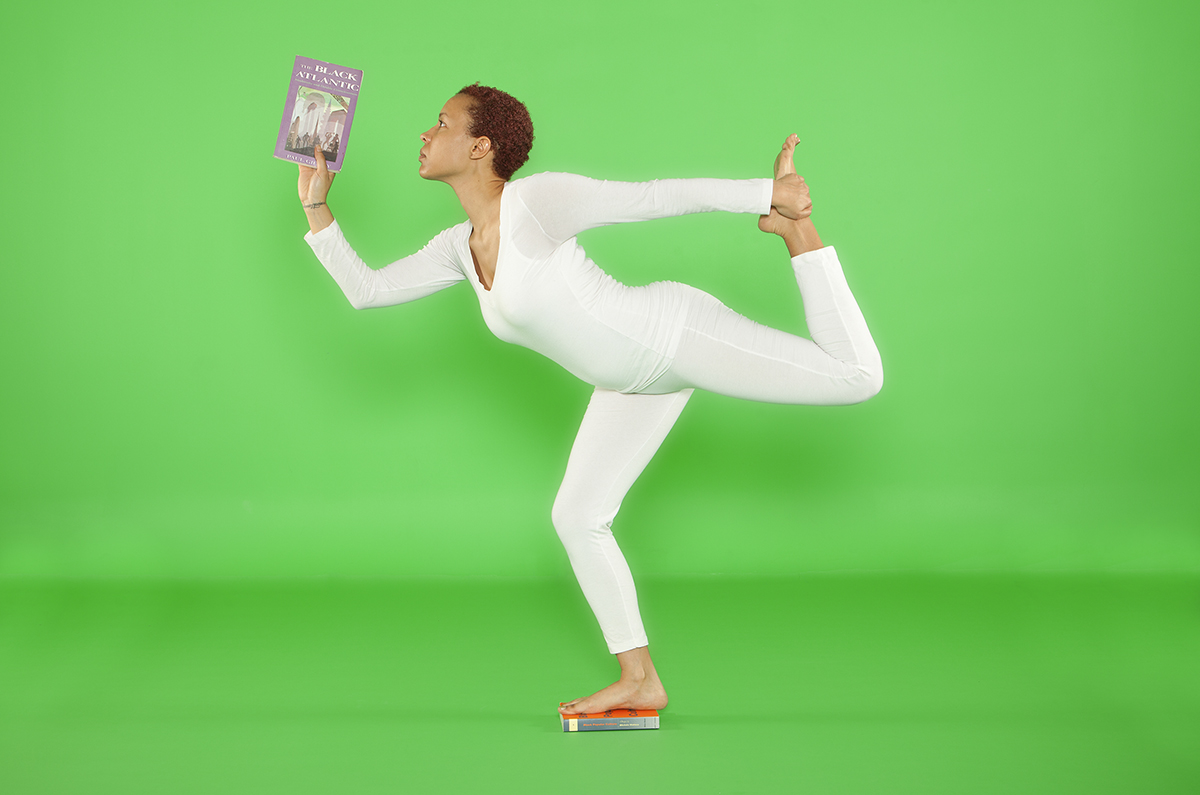

The other side of gallery space contends with her enduring cultural influence and its impact on musicians and artists, pop and otherwise. Harold Offeh, a London-based performance and video artist, filmed a live action version of himself attempting the famous arabesque pose from the cover of Jones’ 1985 album Island Life.

Unlike Jones, Offeh is nude as he stands with his limbs outstretched (Jones’ body is selectively wrapped: an ankle, a wrist, her breasts). His round stomach lacks her body’s sculptural ideal, and he’s all the more human for it. After holding something like her pose for a minute, he loses his balance, utters a sigh, and the film begins again. It’s a witty piece that exposes the album cover for what it is: a cut and paste technique — a pre-Photoshop illusion — by the photographer Jean-Paul Goude.

In a deliberate omission, Goude is not represented in The Grace Jones Project. He may not have been the sole decision maker of her aesthetic sensibility, but while they were a couple he was responsible for much of it. Goude photographed and designed her album covers and directed many of her first music videos.

His 1982 book of photography, Jungle Fever, features a notorious image of Jones naked and caged. Goude, a white man, revels in the need for art to shock for the sake of attention. His “Break the Internet” photographs with Kim Kardashian for the November 2014 issue of PAPER magazine were no exception.

This outré aspect of their work together brings this question to mind: In what context has the art of Grace Jones actively retained its influence?

The collection of vinyl on display at MoAD belongs to the exhibit’s curator Nicole Caruth, but The Grace Jones Project is not simply the tribute project of an ardent fan. When Caruth first saw the video for “La Vie en rose,” Jones, tangling with an accordion, was for her a figure of female and Black empowerment (Jones moved from Jamaica to New York as a teenager).

Many of the installations on display contend with and embrace Jones’ projection of Black strength. Photo shoots like the one she did for Playboy in 1985, with her then-boyfriend Dolph Lundgren, reinforced the mythology of her physical perfection.

But her oeuvre largely resides within the realms of pop culture, where attention-getting is the end game. It’s easy to see where Rihanna, Lady Gaga and Nicki Minaj often draw visual inspiration, sometimes borrowing directly from Jones’ wardrobe. But it’s difficult to compete with the lasting impression made by a suit made of meat.

Heather Hart’s mixed media collage Jumeaux (twins) claims Grace Jones as more than mere pop artifact. Hart says, “In pop culture we found her in chains, in cages, with raw meat, put into the position of the savage animal. But because of her command, because she was tall, because she was androgynous, because she had power in her own gaze, somehow I didn’t doubt her agency as a subject.”

Two images of Jones nest inside a circle of light in Hart’s collage. The viewer is instructed “to press one piece of gold leaf” into this space on the canvas. For Hart, this action is meant to refute the idea that Jones was just a puppet in Goude’s hands.

Hart’s collage, and the diverse range of other contributions in The Grace Jones Project make a convincing argument for Jones’ status as an icon of Black female empowerment, and as a seminal figure in the landscape of pop culture.

The Grace Jones Project is on view through Sept. 18 at the Museum of the African Diaspora in San Francisco. For tickets and more information visit moadsf.org.