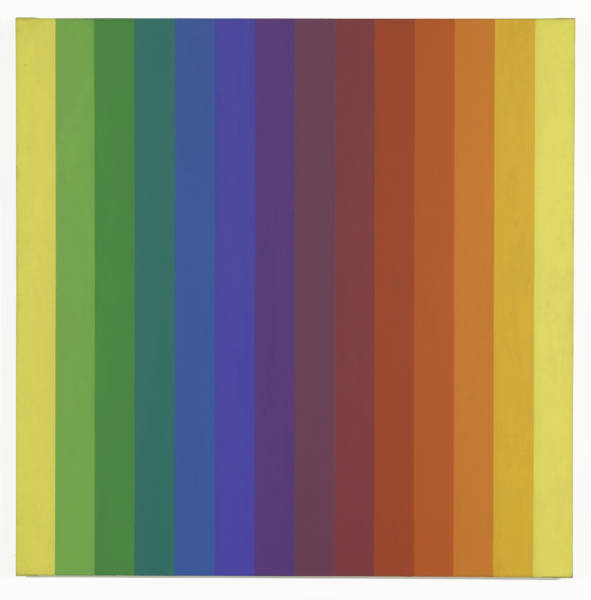

In one of the galleries in the spacious new wing of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), triangular and oval canvases painted in bright oranges, yellows and greens by Ellsworth Kelly swirl around the visitor.

SFMOMA’s senior curator of painting and sculpture, Gary Garrels, says this room is one of his favorite places. “It’s just so jubilant and exuberant,” Garrels says. “Kelly always said he was happiest when he was in a studio. And he hoped that some of that happiness would be experienced when visitors saw his work out in the world.”

The room is just one of many, many galleries in the museum’s new $305 million wing, designed by the architectural firm Snøhetta.

When it reopens on Saturday, May 14, after three years of closure, SFMOMA will become the largest modern art museum in the country in terms of square footage. The new building has almost triple the gallery space of the old Mario Botta building, completed in 1995. The museum’s permanent collection has grown to 33,000 works of art.

Kelly’s paintings are from the collection of Don and Doris Fisher, founders of The Gap clothing chain. Their son, Robert Fisher, now president of SFMOMA’s board, says his parents developed some serious, even obsessive collecting habits.

“You see something you love. You buy it, you enjoy it,” Fisher says of his parents’ passion for collecting art. “And then you see another thing you might love, and then you see another thing you love, and another thing. Then your walls are full at home. So what do you do?”

The Fishers displayed their work at The Gap headquarters. Then, eight years ago, they abandoned a plan to build their own museum in The Presidio, and made a long term loan to SFMOMA of 1100 paintings and sculptures. During the construction of the new wing, SFMOMA director Neal Benezra persuaded other donors to promise thousands more artworks to the museum.

“The collection we now have is as good as any in the world,” Benezra says. “Not just the numbers of works, but also the quality of works and the depth of our holdings.”

A “who’s who” of the modern art world

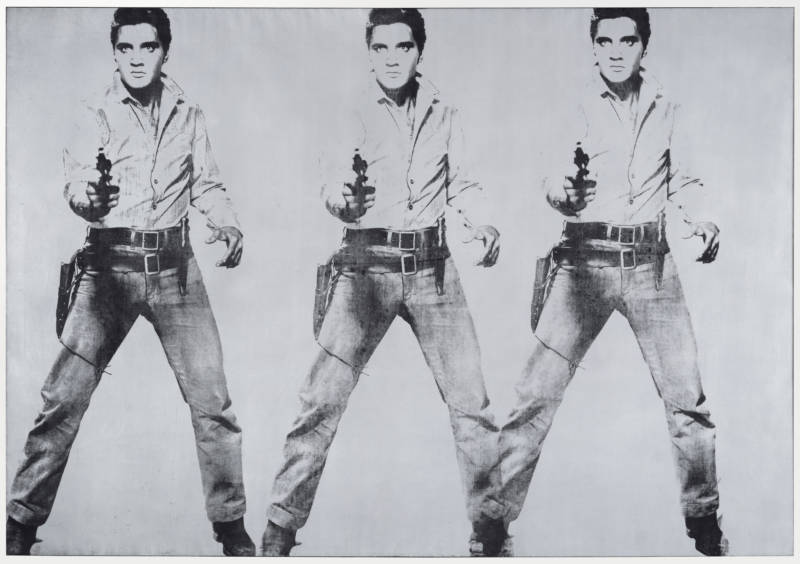

Much of the new wing is filled with what amounts to a “who’s who” of famous mid- to-late-20th century artists, many of whom became personal friends of the Fishers. There are deep dives into the work of pop icon Andy Warhol, photorealist Gerhard Richter, photographer Chuck Close, and sculptors Richard Serra, and Alexander Calder, to name a few.

What’s missing?

But for all of the newly-expanded SFMOMA’s bounties, a number of critics have voiced concerns about what’s missing.

“It’s very, very obvious,” says Dena Beard, executive director of The Lab, an experimental gallery in San Francisco, and a former curator at the Berkeley Art Museum. “They’re missing women and people of color in their collection.”

SFMOMA has been quick to defend itself against such critiques. Garrels says the museum is working to fill in the gaps, for example through such recent acquisitions as an intimate, candid portrait by the American artist Alice Neel depicting a gay male couple sitting together. “It’s the first painting of Neel to come into the collection,” Garrels says.

The Neel is next to Edward Hopper’s famous portrait of a woman in a movie theater, and a collage by African-American artist Romare Bearden — the first Bearden to come into the collection.

Do big donors call the shots?

In addition to the under-representation of non-caucasian and women artists in the Fisher Collection, there’s another ethical question to consider about how museums decide whether art is worth displaying or not when they’re offered a major donation.

“Are we owned by our patrons, or are we owned by the curatorial vision?” Beard asks. “How do we determine value when we require so much actual dollar sign value from these people.”

Such issues have often been swept aside in the history of modern art. New York’s Whitney and Guggenheim museums were both founded by their wealthy namesakes. Music mogul David Geffen recently gave New York’s Museum of Modern Art $100 million for a new wing, and businessman Eli Broad has invested around $1 billion dollars in museums in Los Angeles, including building and endowing The Broad Museum devoted to his own art collection.

But Garrels says he frequently declines the offerings of potential donors. “There are private collections that would not have been of interest to the museum, where we just feel the work is not of the caliber or quality that we want to maintain for this collection,” Garrels says.

Fisher Collection draws praise despite criticism

In spite of the criticisms, many art world insiders have praised the quality of the Fisher Collection. Beard says she was moved to tears by a room full of Agnes Martin paintings — seven minimalist paintings in deep blues and white-washed colors that seem to float off the canvas. “It is absolutely stunning,” Beard says. “And they’re moving. They’re something you want to spend hours and hours with.”

Shannon Jackson, associate vice chancellor of arts and design at UC Berkeley, says the agreement between the Fishers and SFMOMA was a deal worth making.

“By donating a huge collection to a publicly minded institution, it is now possible for all of us citizens to see these works,” Jackson says. “And we don’t have to wait for an invitation to the Fisher’s house for dinner.”

As SFMOMA opens to the public, visitors will be able to make their own judgments about whether it is both a big museum — and a great one.