Imagine a constellation of images that span the last one hundred years, accumulating and gapping as heights of activity ebb and flow over the course of a century. This circular map of experience weaves through time, echoing the staccato and reverberating conditions of long-term memory.

New experiences call up past occurrences and become arranged, overlapped, and clustered according to sight, feel, effect or impact. As an archive, this sequence follows a uniquely human logic, subjective and driven by impression and visceral observation as opposed to an organization based on time and topic. This archive is not adequate in its ability to represent the past accurately as it happened, but rather it’s sufficient at representing the poetry and cadence of memory itself.

Collected Shadows is on view at Pier 24 Photography as part of the current exhibition Secondhand, which features a selection of artists who mine existing archives of mostly found images from which they appropriate, manipulate, edit and sequence in order to create entirely new works of art. Collected Shadows is one of the London-based Archive of Modern Conflict’s (AMC) curatorial projects. Organized by the AMC’s director and curator, Timothy Prus, it is a semi-encyclopedic and enigmatic display with an accompanying book that spans a wide range of subjects and time periods.

The exhibition includes 238 photographs hung salon style through three galleries, the immense array forming a universe made of clusters that only reveal their logic over time, if ever. Positioned mid-way through the vast exhibition space, there is a curiosity cabinet quality to Collected Shadows that is emphasized by the varying images set against striking dark plum walls (described here by Timothy Prus as “nocturnal purple”).

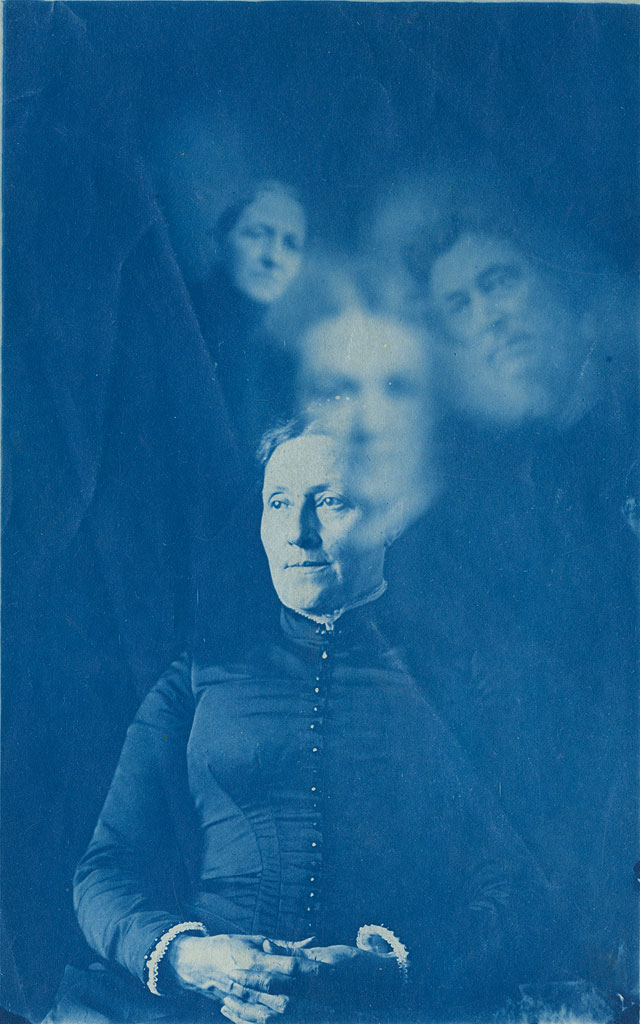

The expanding map of photographs is revealed around each corner, some images hung well below eye level, and some inching towards the ceiling. There is a rhythm of bright blue from the regular cyanotype print on each wall, punctuated by an occasional rich c-print amidst black and white or sepia photographs.

The initial experience of the show is remarkably aesthetic, while the content of each arrangement unfolds over time. The display is visually seductive, supporting documentation that feels familiar, even if seen for the first time.

An entire wall is dedicated to the subject of the ocean, and includes photographs taken from the beach or from a boat. Some depict leisure while others refer to the other predominant industrial-age job of the sea, as a bearer for commerce and transportation.

The next wall is more cryptic and includes religious iconography, occult references, or the last moments of Kazimir Malevich, and then gives way to clinical views of natural specimens and x-ray images.

Around the corner, a wall of women posing for the camera is woven through with images of clouds, while on the next wall, portraits of men mix with depictions of planetary surfaces.

Ensembles rythmiques et gymnastiques a Pekin, 1965; Courtesy The Archive of Modern Conflict and Pier 24 Photography, San Francisco

As groupings become clear, the logic behind their order remains fairly opaque. Attempts to find a linear thread from beginning to end never fully coalesces before you are then led to the next burst of activity.

‘To archive’ is defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as to ‘place or store in an archive’. Typically connoting organization along historical or topical lines, there is a sense of inherent hierarchy and institutionalization within the gesture. However when defined, the word still remains somewhat open and self-referential, a loop that contrasts with its impression of an activity that creates clarity and order.

In Archive Fever, originally presented as a lecture titled “The Concept of the Archive: A Freudian Impression” given in London in 1995, Jacques Derrida describes the archive as “only a notion, an impression associated with a word, and for which, together with Freud, we do not have a concept. We only have an impression, an insistent impression through the unstable feeling of a shifting figure, of a schema, or of an in-finite or indefinite process.”

In-definition and in-finite-ness are apt terms to describe both Collected Shadows and The Archive of Modern Conflict. An institutional title that creates the anticipation of sobering material, the archive is actually more indeterminate and wandering in its collection.

Moving through the exhibition at Pier 24, there are images of what look like burning barns and depictions of atomic tests from World War II — one of the topics from which the archive began twenty years ago. But there are also images of domestic scenes, landscapes and plants, families and outer space, many of unknown origin. The breadth of the representations in Collected Shadows could be described as alternating views of civilization in the nineteenth and twentieth century. There is a broad lens, with moments of specificity.

As far afield as the images go, it’s not difficult to circle back to conflict, which ultimately reaches into each area of private and public life. The wall dedicated to aerial photography includes documentation of expansive areas of land and parachutists taken from the sky, referring to a time when aerial technology shifted the way humans interacted with one another, especially during times of combat. Balloon warfare began as early as the eighteenth century, but fully mechanized aerial military engagement really picked up in World War II, introducing broader destruction, as well as the need to make newly electrified cities invisible to the sky through wartime blackouts.

Returning to the constellation, the inevitable gaps between image groups, like blacked-out cities invisible from overhead, exist with activity, even if unseen. In Collected Shadows, the photographs in each cluster represent distinct moments in time — people, places, or occurrences — while also referring to pivotal turns in history or moments of collective experience. The images rely on both their context within a particular group of images and the memory of the viewer. What each references can often change according to where it is placed, or its categorization within the archive. In this sense, the organization is both sufficient and inadequate in its coverage, inevitably always leaving a blacked-out gap.

Secondhand runs through May 2015 at Pier 24 Photography in San Francisco. Read KQED’s review of the full exhibition. For more information visit pier24.org.