It’s tough not to be dazzled by Glamorgeddon: the Spectacle, on view until Feb. 4, 2015 in SOMArts’ Main Gallery. The lofty gallery walls confidently don hot pink, along with neon colors and splashy camouflage. Glamour, in this sense, takes the visual articulation of consumer and commercial desire up a notch or two. Objects from everyday life and popular culture are refigured and dressed up. Sparkles, a roving hot pink limousine, glitter, swag—this is a bedazzled bonanza.

But while work and fun are confounded with a bit of playful snark, don’t let first looks fool you—these works aren’t dressed up for just anything.

The group exhibition curated by Bay Area artist Johanna Poethig, along with Angelica Muro and Hector Dionicio Mendoza, brings together work from over twenty artists and performers in SOMArts’ first of three 2015 Commons Curatorial Residency exhibitions.

Glamorgeddon, the title itself, suggests a conflict. Popularly, the idea of glamour gets mired in specifics: who has it, how they got it or why they have it. But Poethig distills glamour down to its definition as the quality that makes some more appealing, or special, than others. Glamour becomes a strategy that these artists suggest can be used to negotiate complicated socio-political experiences, and embraces it in order to confront colonial histories and empire building.

Amalia Mesa-Bains' distinctive shrine, El Fin del Siglo: Latina World’s Fair (2000), on one hand, appears to pay homage to “Latina glamour girls,” representing such icons as Frida Kahlo and Margarita Cansino (well-known by her Hollywood name, Rita Hayworth). These images, situated on a digital collage, serve as a contested backdrop for five small figures formed diligently from bent wire that stand on a table draped perfectly with silver fabric. While this can be read as homage to a history of iconic Latinas, the miniatures, which model a range of glamorous dress, also emphasize a certain cultural “on display-ness” that harkens back to world’s fair ethnographic showcases. Mesa-Bains’ shrine empowers Latina bodies and histories while also pointing to the complicated cultural fetishizing that is still engrained in societies built on colonial pasts.

Such conflict in Mesa-Bains’ work runs through the entire show. Like the concept of “cool,” glamour is not fixed. It is more easily defined by what it is not than what it is. Glamour morphs and changes based on cultural context and consumer audience—producing desire as equally as depending on it. In this way, glamour is a fruitful strategy for Poethig’s curatorial concept, where the creation of desire plays a fundamental role in the maintenance of a consumer experience. Glamorgeddon draws connections between a global consumer society and the history of colonialism in the Western world, and specifically in U.S. history—with no less sass and flair.

Much of the work in the exhibition points to consumer visual culture. Joyce Hsu’s Hello Kitty and Gundam Posters and Dolls (2015) brings together two of Japan’s wildly popular animated media franchises and global phenomena, Gundam Series and Hello Kitty. Hsu playfully refigures the characters together, hinting at the way unto which pop culture is often looked in order to construct new imaginaries of the world. Mesa-Bains and Hsu’s work demonstrate how appropriation functions both as empowering strategy or cultural fetishizing—and sometimes both.

Towards the back of the gallery hangs a grid of four large digital photos in the series Manananggoogle (2013) by Mail Order Brides/M.O.B., the collaborative trio consisting of artists Reanne “Immaculata” Estrada, Eliza “Neneng” Barrios, and Jenifer “Baby” Wofford.

In the first image, the three artists pose self-assuredly around a conference table; their beige suit jackets seem almost vibrant compared to the dull neutral palate of the drab corporate world. The perfectly sterile and impersonal room matches their no-nonsense poses jarred only by their chalk white painted faces. This is not your typical office.

Over the course of the four images, the veil of corporate bliss falls apart, as it so often does. The three “suits” seem to sprout wings, go demon-wild, devour plates of meat with vampire-like hunger and oh… the intestines—so much intestines.

Manananggoogle appropriates the aesthetics and language of the corporate tech industry and satirically points to its inherent colonial vernacular—one meant to create desire for innovation and new technological horizons, but in fact reiterates pre-existing colonial rhetoric. Their website, positioned as a satirical performance of an actual tech company, posits a corporate mission statement that, when reframed as a critique on empire-building, doesn’t sound dissimilar from that of Christian missionaries of the latter half of the 20th century.

M.O.B. appropriates the seductiveness of the current tech industry and glamorous corporate society in order to reposition new, innovative and rapid tech-lust as old-shoe latent colonial hunger.

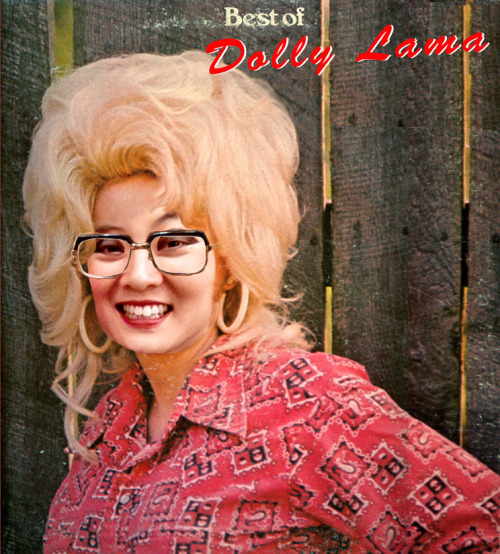

Glamour is a visual project that at its core produces difference, and hence what is not glamorous is equally as meaningful. Musician Theresa Wong, one of the performers at the opening events, has a small print in the swag area of the exhibition. Wong Photoshopped her face onto Dolly Parton’s using the cover of her 1975 Best of Dolly Parton (Vol. 2) album. The image of Parton—huge blond hair and bosom to boot— is ruptured by Wong’s Chinese features superimposed onto the recognizable idol.

This small and humorous gesture is apt, as it calls out not Wong’s desire to be Dolly Parton but the viewer’s question of if Wong belongs to this body, hairstyle, genre and ultimately culture. The artists in Glamorgeddon tactically manipulate the accoutrement of glamor to critique their own global systems of capitalism and colonialism. They critique and celebrate, but they also call out the viewer’s ingrained ideas about who is different, and which bodies belong.