Inequality and police brutality aren’t exactly new, but social media is. And in reaction to the recent spate of killings of unarmed black men, which have been well-documented by smartphones and online sharing, society is once again revisiting the issue of racism. The feelings of grief and frustration among black youth and those in solidarity can be seen in the #BlackLivesMatter movement, which has brought millions of people together in protest of police violence.

Sometimes, certain aspects of street protests stray from the core idea of what it means to be young and black in America. But a handful of local artists are taking back that idea by creating a space—through their art—to heal from the systemic racism that breeds fear, self-doubt and self-hatred within black communities.

Amir Aziz is a graphic artist, photographer and Oakland native who’s part of the Bay Area art collective Youthful Kinfolk, a group of young people interested in pushing Bay Area art and culture further. Aziz chronicles the movements that sprout from the deaths and resulting trials of unarmed black men, putting them together in a “collection of unity.” His collection demonstrates how Oakland’s young people of color interact with various events happening all over the nation. “I go to these events and I document them, and I want to share that with everyone—share what you miss when you’re not in this part of Oakland that you may not be too comfortable with,” Aziz says.

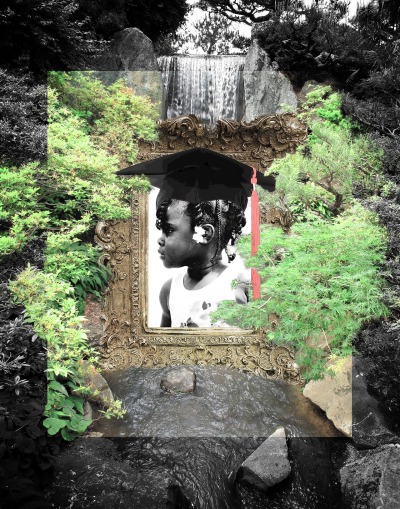

He also focuses on photo manipulation inspired by Afrofuturism, the movement of black sci-fi and fantasy culture born in the late 1970s (think Parliament, Sun Ra, Octavia Butler and, more recently, Janelle Monáe).

If approached at random on the street and asked, “Are the lives of black people just as important as the lives of white people?,” most people would likely say yes. Yet at the same time, young black children all over America struggle to find positive role models and depictions of themselves in the media. How are they supposed to plan a future? That’s where Afrofuturism comes in.

Aziz’s work projects a positive future for black people, outside of the stereotypical box. “I just like projecting so-called blackness in the past, present and future,” he says. “I like to look toward our future and create realisms for us and alternatives.”

As Aziz says, “We may not always have [healing spaces] or know where to find them, or know they exist. I think art is one of the ways that you can have a healing space.”

Find Amir Aziz on Twitter as @amirazizme.

Writer and spoken-word artist Roselyn Berry, a.k.a. Lady Rose, has dedicated her life to uplifting African American communities. She’s been involved in social justice work for the last 14 years—11 of those in Boston, where she marched in solidarity for Oscar Grant, and three in the Bay Area.

“Having to see your folks be dehumanized and murdered over and over and over again, it’s just overly traumatizing and it’s difficult,” Berry says. “As an artist, it’s both what drives me to want to produce and it’s also what makes me feel like I can’t produce. It’s so personal, and it takes you to a place where I think sometimes my brain can’t even be creative, because it’s just too hard to deal with the reality of it.”

She struggled to write her piece titled “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot” right after Michael Brown was killed. It’s one of the only pieces she’s released to the public since. The overwhelming reality of the situation made it difficult for her to open up and channel the raw frustration and rage she felt into her writing.

Nevertheless, Berry forces herself to write in such moments of urgency, because it enables black people to tell their stories and heal.

“Any time a life is lost, especially when it’s a life of a black or brown person, whether I knew them or not, it feels personal to me,” she explains. “Because we’ve lost someone from our community. Because we’ve lost another soldier. Because we’ve lost another warrior. And regardless of whatever judgements folks had about how those people lived their lives or whatever decisions they made—which none of us really know anyways—it’s still another life.”

As a social justice worker, Berry is familiar with the issues that over-policing causes in black communities, but it doesn’t stop the hurt. She wants to see more at the rallies, protests and marches. Not just chanting or spoken word, but full ceremony, song and dance. “We’ve gotten to a point where we start to view creative expression as an accessory to the movement, or as something that we integrate as opposed to a centerpiece,” she says. “I’d like to see us start to recognize that freedom of expression has always been a tactic that our folks have used to come together around, and we don’t do enough of it.”

Find Roselyn Berry on Facebook as Lady Rose.

A traditionally successful access point for black communities is hip-hop, an artistic space of healing, political engagement and success—particularly for black folks. DetermiNation is a black men’s group affiliated with United Roots Oakland. The group gives young men ages 19-26 a space to learn, to heal from the trauma of lives characterized by poverty and drugs, and to focus on what they want to affirm in their future as opposed to what their life is about in the present.

For the men of DetermiNation, the death of a peer is nothing new. It’s part of the daily struggle that’s plagued African-American communities for centuries.

Group facilitator Adimu Madyun encourages the men of DetermiNation to focus on improving themselves mentally, physically, spiritually and emotionally through art. To Madyun, music is an integral part. He also tells his men not to get too deep into protests and instead focus on empowering themselves first, so as to make their families, organizations and communities strong.

“The world of the protests can be very confusing, because they get out there and march with all kinds of people, and then they realize they still have nothing,” Madyun says. “When the protests are done, they are still on the street.”

When first creating music, many of the men in DetermiNation rap and sing about “terrible stuff,” Madyun says, citing sexism, violence and drugs—subjects more ‘ratchet’ than political. But Madyun lets them work through that, and then provides them with a solution. “You have to talk and teach and sell what social responsibility is, he says. “You have to get them excited about being responsible.”

DetermiNation provides an environment for men to critique one another and show love in order to get to the next stage of creating art with a social message. In the song “Living Wealthy,” for example, Madyun raps about healing the men, as the others rap about seeing their community overcome racial and economic inequality.

Find DetermiNation on Twitter as @DetermiNationMG.

Richmond hip-hop artist Sudan Williams, a.k.a. IAMSU!, was a youth leader before he started making music full-time—and now he’s got the ear of the people. As a talented rapper and producer whose social media game is on point, Su’s following expands well beyond the Bay Area and the United States.

Su’s at that artistic sweet spot: on the creative come-up, but not too good for his mom’s house in Pinole. “I come here and I have to deal with the problems that go on here,” he explains, “so this is what directly affects me. So I consider myself a local artist, the things that I convey in my music are all things that I’ve seen living out here.”

As a musician, he’s been making music with good vibes. But the momentous energy of recent events within the black community have him thinking about the type of artist he wants to be. Normally, he just reports his experience as a young black man, be it the struggle of his peers or simply being in the club. But “lately I’ve been having a conflict of what I talk about in my music, just because of these things that are going on,” he reports. “I’ve been having trouble approaching things the way that I used to. I know I need to be more attentive to what I’m actually saying in my music, and I want people to take [away] something of value.”

His debut album Sincerely Yours came out in May of last year. The song “Problems” touches on the issue of black people’s struggles, such as enduring the world’s limited historical perspective on black lives, obstacles to buying real estate, and more.

Ironically, Su’s hesitant about being too political and preachy in his music. His place of healing comes primarily through conducting toy- and backpack-collection drives in Oakland. Su’s challenge is in how he can lead people away from fear and self-hatred while growing as an artist that’s true to himself and his own personal progression.

Or, as he puts it: “The generation that I cater to isn’t really receptive to being just badgered and harassed with a message, you know?”

Find IAMSU! on Twitter at @IAMSU.