The story of French artists Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore—neé Lucy Schwob and Suzanne Malherbe—is long and rich enough to fill multiple exhibitions, or multiple volumes.

But here’s the abridged version: They met as teenagers in 1909 and were inseparable until Cahun’s death in 1954. In the intervening years, Cahun and Moore moved to Paris, published books together, worked on experimental theater productions, participated in the Surrealist movement and staged political actions. Facing increasing anti-Semitism, they relocated to the island of Jersey in 1937, where they waged a two-woman propaganda war against Nazi occupying forces during World War II. They were arrested for their troubles, and sentenced to death by soldiers who couldn’t believe two middle-aged women were responsible for so much unrest. They were liberated, with the island, after spending a year in prison.

![Claude Cahun (Lucy Schwob) and Marcel Moore (Suzanne Malherbe), 'Untitled' [I am in training don't kiss me], 1927.](http://ww2.kqed.org/arts/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2019/02/04_ShowMe_Cahun_Moore_1200.jpg)

And throughout their relationship, they made art, a body of work “rediscovered” in the 1980s to fill an unknown gap in the lineage of queer, gender fluid, surrealist portraiture.

Show Me as I Want to Be Seen, the current group exhibition at the Contemporary Jewish Museum organized by assistant curator Natasha Matteson, uses Cahun and Moore’s collaborative photography as a jumping-off point to examine themes of identity (its performance, legibility and slippage) in the work of ten contemporary artists.

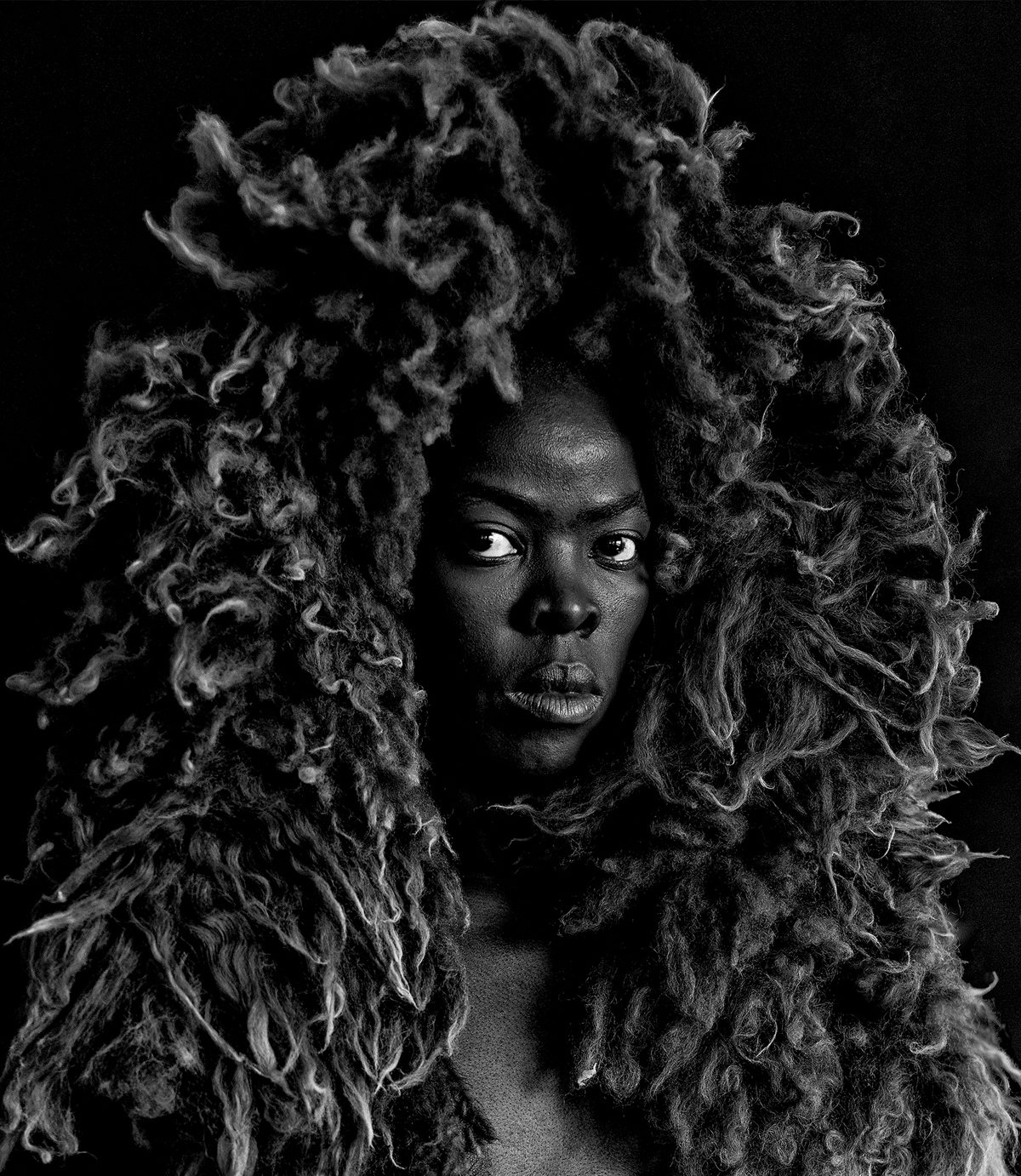

Of those, the clearest inheritor of Cahun and Moore’s subversive legacy appears in South African photographer Zanele Muholi’s staged self-portraits. In high contrast black-and-white gelatin silver prints, the artist poses in costumes fashioned from ordinary household objects—latex gloves, paper, a handbag—usually staring directly into the camera. Like the many photos of Cahun sporting theatrical makeup, Muholi darkens their skin in these images, a gesture of “reclaiming blackness” and forcibly confronting white supremacist notions of beauty. The results are striking.

While most of Muholi’s contemporaries in Show Me deploy images of bodies to some extent (the lone exception is Davina Semo’s sculptures, where the artwork titles carry the weight of personhood), some tread more closely to Cahun and Moore’s penchant for surrealism than portraiture.

In Los Angeles-based Gabby Rosenberg’s discombobulated paintings, rendered in acrylic against black grounds, she cuts up figures, peers into them and jumbles the parts with thick brushstrokes. In Fake Friend Frankenstein, the man (or monster) waves despondently with a mouth that looks like raw meat, three teardrops spouting from one eye. The title tilts its reading: Is it someone reaching out for connection across the awkward distance of a social network?

Matteson’s wall text refers on multiple occasions to social media. And it’s easy to see the fragmented, constructed and multiplied self played out across posts on Instagram or Facebook as prime fodder for artmaking.

Rhonda Holberton’s Just This One Thing—part of the show but only visible to those who have the wherewithal to scroll through the Oakland-based artist’s Instagram feed—skewers the spare, ecru-hued “Instagram aesthetics” of influencers’ lifestyle posts.

A croissant, a stack of baskets, handmade ceramics—Holberton creates the images by 3D-scanning actual objects and staging them in virtual space. In a quick scroll-by, the digital fabrications appear innocuous, ordinary. Only close inspection reveals them to be oddly pixelated approximations. Tagging each image #stilllife, along with hashtags like #rainydays or #sundaymorning, Holberton launches these interruptions into the stream of “real” Instagram posts, themselves approximations of actual lives.

Show Me embraces the idea of an unfixed, nonbinary, constantly permuting self not only in its curatorial selections, but in its exhibition design, mingling the contemporary artists’ work with Cahun and Moore’s photographs. As might be expected in that mix, details get lost and overlooked. The base of Young Joon Kwak’s delicate Hermaphroditus’s Reveal I, for instance, nearly blends into the museum floor. A pedestal bearing anti-surveillance scents by Holberton sits, rather arbitrarily, against one end of a diagonal wall.

Underlying everything, it’s the comparison between a shared life’s work and multiple small bodies of work (or, in some cases, just a piece or two) that creates an imbalance at the heart of Show Me. Though their lives are thinly sketched in wall text, it’s clear that Cahun and Moore’s art is inextricable from the politics they embodied. The depth of their imagery is met, unevenly, by the breadth of the contemporary line-up.

But perhaps this exhibition, like Cahun and Moore’s practice, will serve as a jumping-off point in the viewers’ minds—an introduction to practices that, when fully investigated, will emerge as equally fascinating and vital.

‘Show Me as I Want to Be Seen’ is on view at the Contemporary Jewish Museum through July 7, 2019. Details here.