In Japan, before mass-produced plastic bags took over, a square of cloth served to wrap purchases of varying shapes and sizes. What the Western world may have derided as a “hobo bundle,” was elevated to a visual art, using traditional Japanese cloths called furoshiki.

Pronounced fu-ro-shkee, this cloth and its historical uses can be traced through the word’s etymology: “furo” means bath and “shiki” means mat. In communal Japanese bath houses, many people brought a cloth with them to wrap up their items while bathing and to use as a mat while getting dressed again.

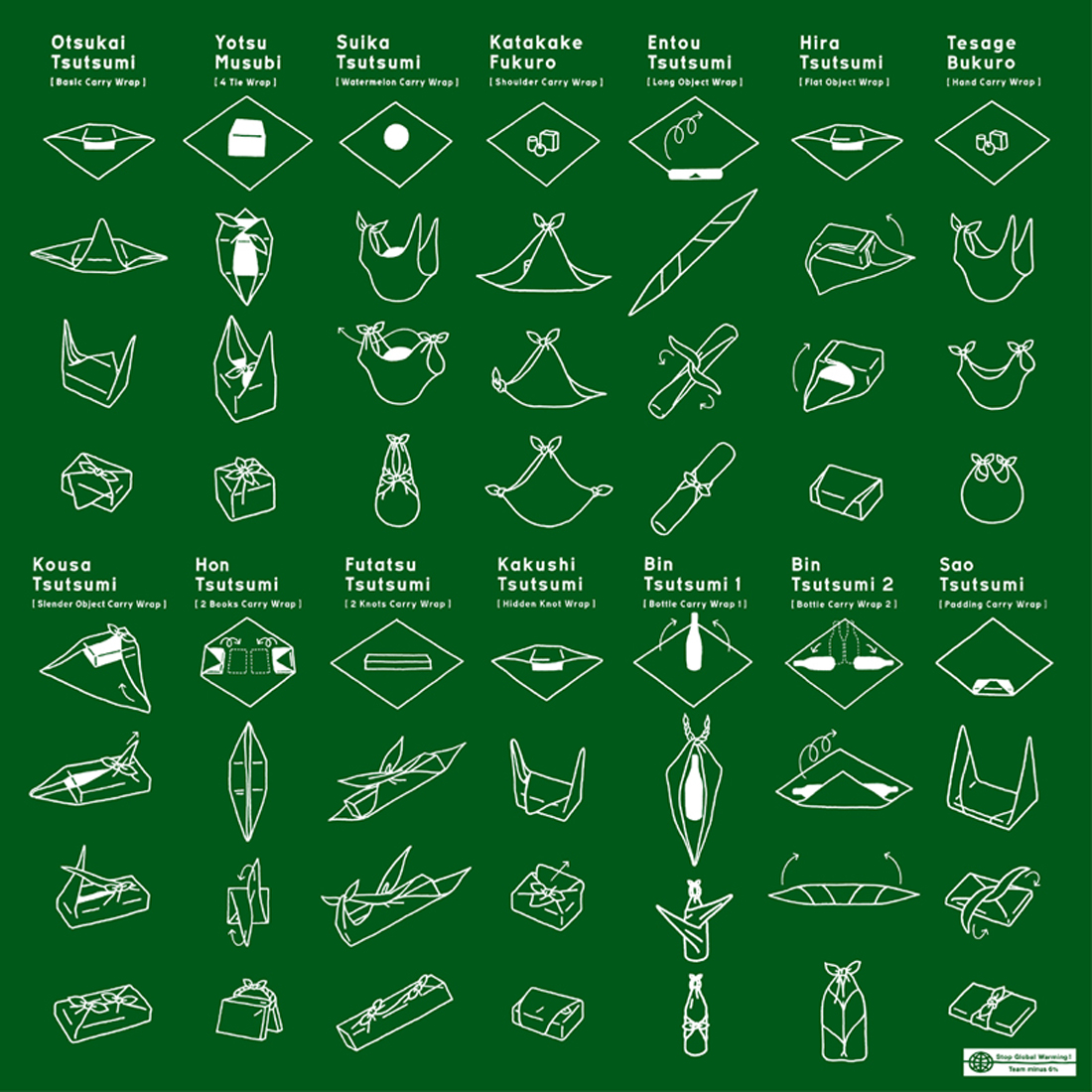

Throughout the years, folding and tying furoshiki has become an art form in itself that demonstrates the utility and elegance of Japanese design. A traditional furoshiki represents thousands of different ways to wrap almost any object, with different colors and designs conveying unique meanings.

A red furoshiki is considered ideal for happy events, while cooler colors like blue are traditionally used for sad occasions. Muted earth tones are chic.

In Japan’s post-World War II economic boom, furoshiki came to be seen as troublesome and old fashioned. Plastic bags were invented in 1965, eclipsing paper bags in the 1990s. And due to its wrapping culture, Japan has been singled out over the years as disproportionately contributing to plastic bag waste by individually wrapping items.

Today, Japan’s Ministry of the Environment hopes to bring this resourceful practice back as a way to reduce plastic bag waste. Beyond being eco-friendly, these stylishly tied cloths represent a different way of thinking.

Vipada Wongpatansin, a San Francisco jewelry designer at CinqWorkshop, sees parallels between the aesthetic qualities of furoshiki and her life as an artist. “I personally relate to furoshiki for its simplicity and function,” Wongpatansin says. “Beyond efficiency, the aesthetic is both organic and modern all at once.”

Vicky Mihara Avery, who demonstrated furoshiki techniques on Martha Stewart’s self-titled television show, explains, “Just the simplicity of having a square cloth and learning how to use that square in many different ways is a very useful tool.” But she admits, “Sometimes simple is difficult to do.”

As a third generation Japanese-American, Mihara Avery understands the differences between the two cultures. “In the United States we like ‘more,’ we like a lot of embellishments, we like a lot of ribbon, and that’s fine too, but the Japanese aesthetic is a little more elegant and simple,” she says.

Much like her grandfather, who published one of the first origami books written in English, Mihara Avery hopes the next generation will learn from Japanese traditions. She carries on this legacy with her sister, Linda Mihara, as Japanese stationary store owners at Paper Tree in San Francisco’s Japantown and Miki’s Paper in Berkeley.

Learn how to tie furoshiki into a simple bag for groceries, a nifty two-pack for beer cans and countless other wrapping styles, from a selection of books available at Kinokuniya bookstore in San Francisco’s Japantown. After learning the basic knots, you may even be inspired to create your own design.

Soko Hardware in San Francisco’s Japantown features furoshiki designed by Clifton Karhu, the notable Japanese-American artist. And although traditional furoshiki can range anywhere from $10 to $100, depending on the size and fabric, any square of cloth can do — because the true spirit of furoshiki is functionality.